Human rights remain the weakest link in global sustainability, with just 26% of companies meaningfully reporting on worker and community risks, even as climate disclosure soars.

The Global Corporate Sustainability Report reveals a widening divide: vast environmental data is shared, while people-centric impacts remain largely invisible, exposing critical gaps in supply chains and transparency.

Europe leads in human-rights disclosure, but regulatory gaps persist globally. By ignoring social risks, companies undermine true sustainability, leaving millions of workers vulnerable.

Human Rights: The Silent Sustainability Divide

Human rights have become the gaping hole in global sustainability reporting, according to the Global Corporate Sustainability Report 2025, which finds that while 91% of global market capitalisation now discloses climate-related information, only 26% provide meaningful human-rights data.

The result is a widening transparency divide: companies are reporting vast amounts of environmental information while remaining largely silent on risks that affect workers, communities, and supply chains at scale.

Across all industries and regions, human-rights transparency lags every major sustainability metric, from environment, governance, and financial materiality. For a global system that relies on millions of workers in high-risk value chains, this gap is more than a reporting oversight. It is a structural blind spot with economic, legal, and social consequences.

Climate and Emissions Reporting Surge – But People Are Invisible

The report's charts show global sustainability disclosure reaching new highs:

- 91% of market capitalisation discloses climate information

- 88% disclose Scope 1 and 2 emissions

- 76% disclose at least one category of Scope 3

But human-rights reporting remains limited to a minority of companies, even in sectors with high exposure to labour, conflict minerals, land rights, or indigenous communities.

Sustainability Disclosure vs Human Rights Reporting

This stark imbalance reflects what the report describes as the "environmental-first bias" in global sustainability frameworks, where climate metrics dominate reporting obligations while human-rights risks remain largely voluntary.

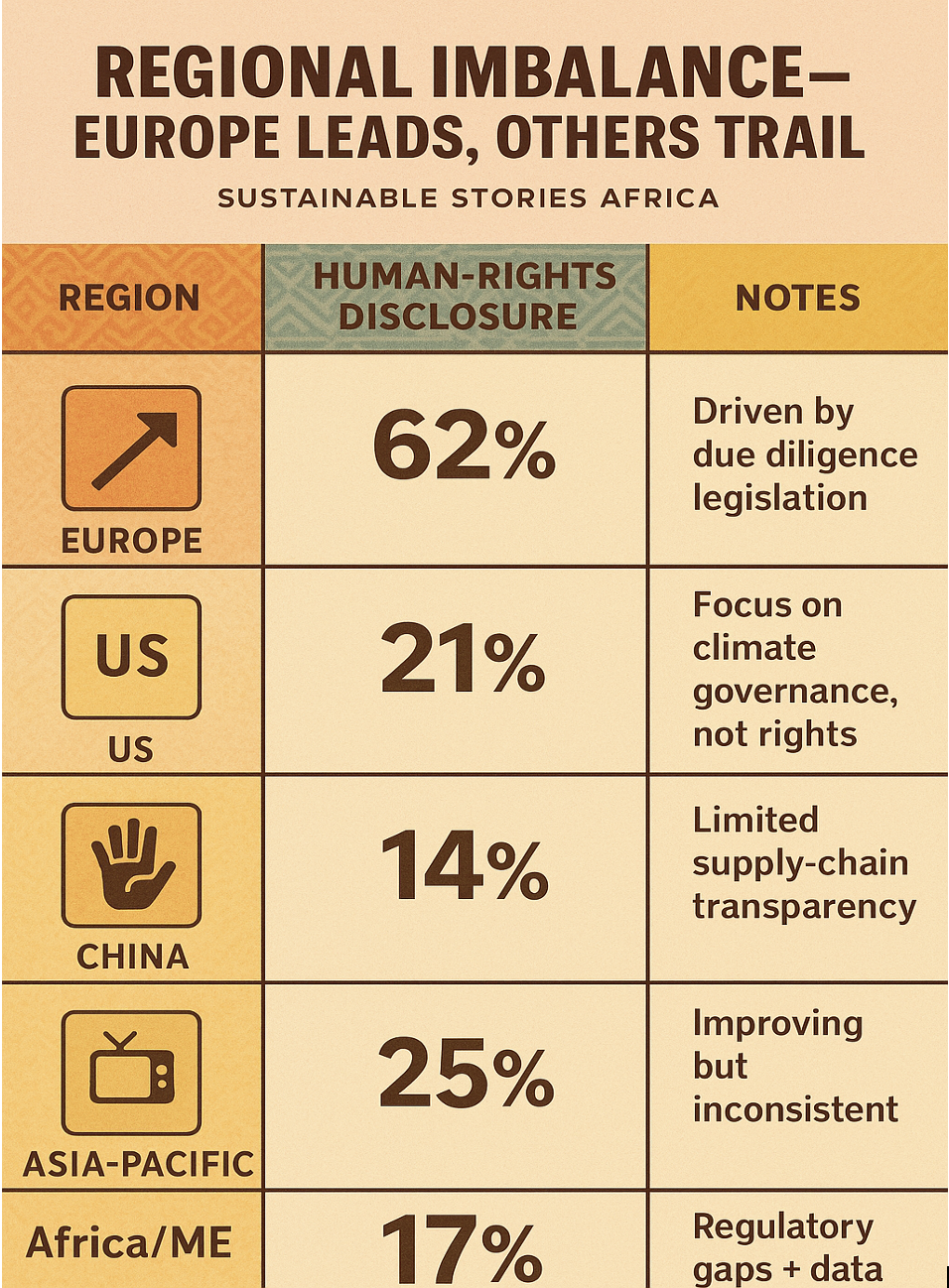

Regional Imbalance – Europe Leads, Others Trail

Europe remains the only region approaching broad human-rights transparency thanks to due diligence laws such as the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). But beyond Europe, reporting drops steeply:

| Region | Human-Rights Disclosure | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Europe | 62% | Driven by due diligence legislation |

| US | 21% | Focus on climate governance, not rights |

| China | 14% | Limited supply-chain transparency |

| Asia-Pacific | 25% | Improving but inconsistent |

| Africa/ME | 17% | Regulatory gaps + data challenges |

This regional gap matters because human-rights risks intensify in global supply chains concentrated in emerging markets.

Why the Gap Exists – A Structural Reporting Problem

The report identifies four systemic reasons human-rights disclosure lags so far behind climate reporting:

- No Global Mandatory Standard – While climate reporting aligns under frameworks like TCFD, ISSB S2, and ESRS, human rights remain governed by voluntary principles such as the UNGPs. Voluntariness equals inconsistency.

- Complex, non-quantifiable risk categories – Where emissions can be measured, human-rights risks require contextual detail—conditions, incidents, audits, due diligence systems. Many companies avoid these complexities.

- Legal exposure and reputational risk – Disclosure may reveal forced-labour exposure, unsafe working conditions, or wage abuses—making silence the safer option.

- Data scarcity in supply chains – Most companies cannot trace their suppliers beyond Tier 1. Traceability systems remain underinvested and fragmented.

The consequence, the report warns, is a global sustainability ecosystem where "people-centred impacts remain invisible at the exact moment the world relies most heavily on globalised labour."

High-Risk Sectors Show the Weakest Reporting

Paradoxically, industries facing the highest human-rights exposure show some of the weakest reporting rates:

- Textiles and apparel — major forced-labour exposure

- Mining and minerals — conflict minerals, land rights, indigenous impacts

- Electronics — cobalt, rare-earth extraction, supplier working conditions

- Agriculture — land grabs, water rights, seasonal labour exploitation

Average human-rights reporting across these sectors is only 24%, compared to 92% for climate-related information.

The Global Corporate Sustainability Report 2025 notes that even companies with strong climate commitments often do not disclose basic human-rights governance structures, supplier audit outcomes, or due diligence coverage.

Human Rights Are Now a Financial Risk – But Not Yet a Reporting Priority

The report stresses that human-rights failures are not only ethical lapses—they are material financial risks. These include:

- supply-chain disruptions

- litigation exposure

- regulatory fines

- reputational damage

- investor divestment

However, because these risks are underreported, they remain underpriced in global markets.

Investors, the report finds, are not systematically integrating human-rights factors into stewardship or capital allocation. Only 12% of global investors request human-rights due diligence disclosures, compared to 48% who request climate data.

The result: a sustainability market that rewards climate transparency but overlooks labour exploitation and social harm.

A Widening Accountability Gap

The report suggests that human-rights due diligence is becoming the new frontier of corporate accountability. While emissions reporting improves each year, global supply chains continue to expand into higher-risk geographies without corresponding transparency.

This gap is especially alarming as geopolitical tensions and labour migration accelerate vulnerabilities in mining, manufacturing, agriculture, and energy.

Where climate governance has rapidly matured, human-rights governance remains surprisingly underdeveloped:

- Only 31% of companies assign human-rights oversight to the board.

- Only 18% conduct full human-rights impact assessments.

- Only 24% have supplier-level grievance mechanisms.

Without these systems, disclosure becomes incomplete—and often misleading.

THE PATH FORWARD – Putting People at the Centre of Sustainability

Human-rights disclosure must move from voluntary to essential. The world's largest companies need harmonised due diligence rules, enforced value-chain oversight, and board-level responsibility for rights-related risks.

A sustainable global economy requires more than climate metrics; it requires transparency about the people who make that economy possible. Until human rights are fully integrated into sustainability governance, disclosure will remain unbalanced, and global supply chains will remain far more fragile than companies admit.