As Africa's debt vulnerabilities deepen, a new conversation is taking shape. One that links sovereign risk to citizens' rights. The World Bank's insight suggests that economic and social rights (ESRs) could redefine how investors judge African nations' creditworthiness.

From education to housing, these metrics may soon become as influential as fiscal discipline in determining Africa's financial future.

Rights, Risk, and Africa's Debt Future

Africa's debt story is shifting. No longer confined to balance sheets or bond yields, the continent's sovereign sustainability is being redefined through the lens of economic and social rights such as access to education, healthcare, food, housing, and work.

In its Equitable Growth, Finance & Institutions Insight series, the World Bank argues that these rights are not abstract ideals, but measurable indicators of a nation's long-term credit strength.

By merging human rights data with sovereign risk assessment, the report suggests a new kind of metric. One that could rebalance the investment scales between Africa's low-income economies and global capital markets.

For investors and policymakers alike, the message is clear: countries that invest in people are more likely to honour their debts. In the post-COVID, climate-stressed era, the correlation between social stability and financial solvency is no longer theoretical; it is becoming empirical.

Beyond GDP: Rethinking Creditworthiness Metrics

Traditional sovereign ratings have long relied on fiscal ratios and external debt statistics. But as the World Bank's report notes, this model suffers from an "ingrained income bias" rewarding wealth, not efficiency.

That bias, it argues, diverts capital away from poorer countries, even when they perform better on social outcomes relative to their income levels. In other words, a low-income African country delivering strong education and healthcare outcomes may appear less creditworthy than a richer peer with weaker governance, simply because the metrics fail to adjust for context.

This structural flaw has real costs. It amplifies Africa's debt-servicing burden, inflates borrowing costs, and constrains social spending.

By introducing Economic and Social Rights (ESRs) as a complementary dataset, the World Bank proposes a corrective mechanism that evaluates how efficiently nations convert income into human development outcomes, thus effectively rewarding "social productivity."

"Countries that use limited resources to expand access to education, health, and work build resilience against shocks and improve debt sustainability," the report notes.

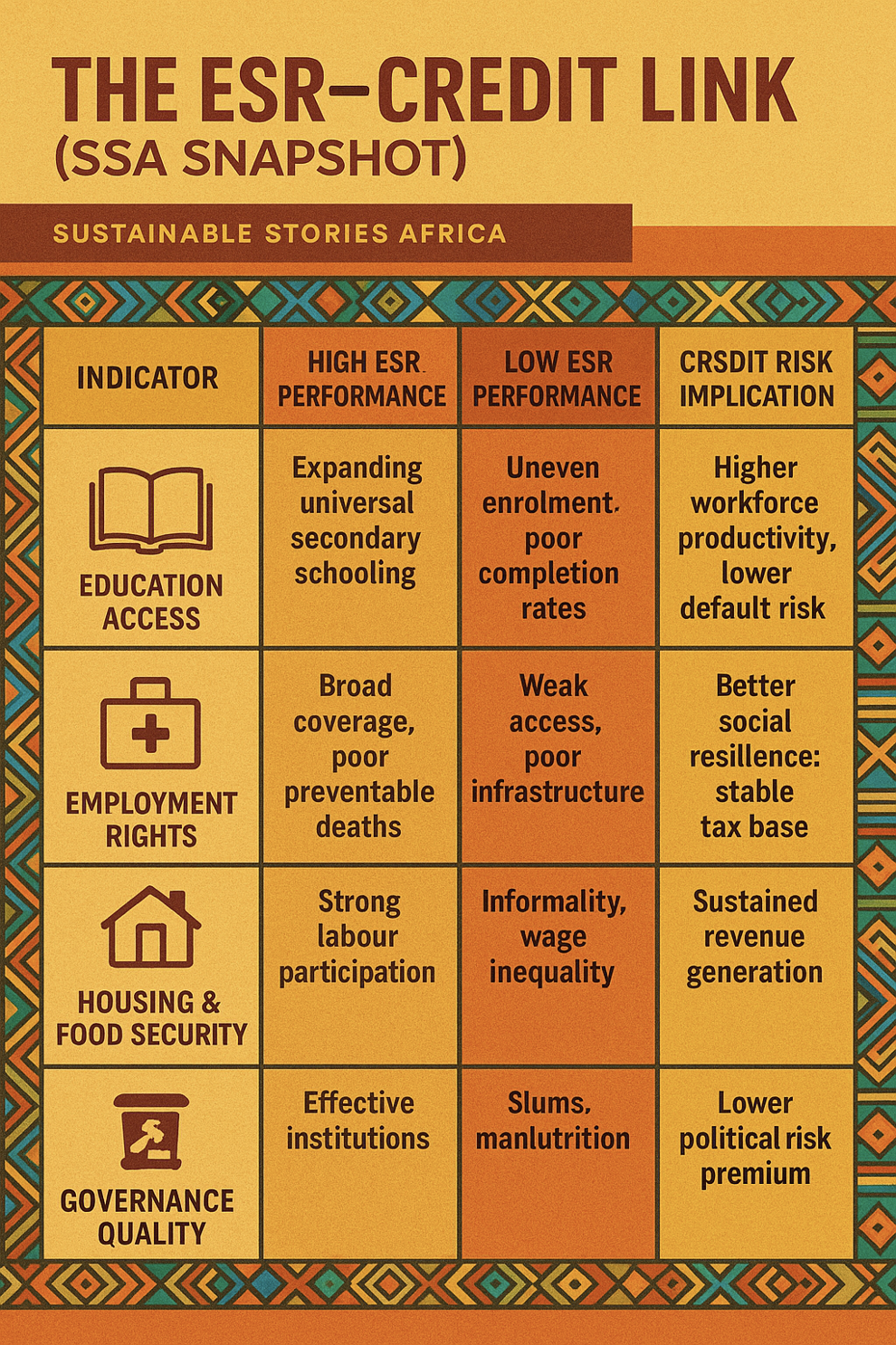

The ESR–Credit Link (SSA Snapshot)

| Indicator | High ESR Performance | Low ESR Performance | Credit Risk Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education Access | Expanding universal secondary schooling | Uneven enrolment, poor completion rates | Higher workforce productivity; lower default risk |

| Healthcare Outcomes | Broad coverage, low preventable deaths | Weak access, poor infrastructure | Better social resilience; stable tax base |

| Employment Rights | Strong labour participation | Informality, wage inequality | Sustained revenue generation |

| Housing & Food Security | Progressive urban policy | Slums, malnutrition | Lower social unrest; stable governance |

| Governance Quality | Effective institutions | Corruption, policy volatility | Lower political risk premium |

The Human Rights Investment Equation

What happens when investors start seeing rights as risk indicators? For African economies, this shift could be transformative.

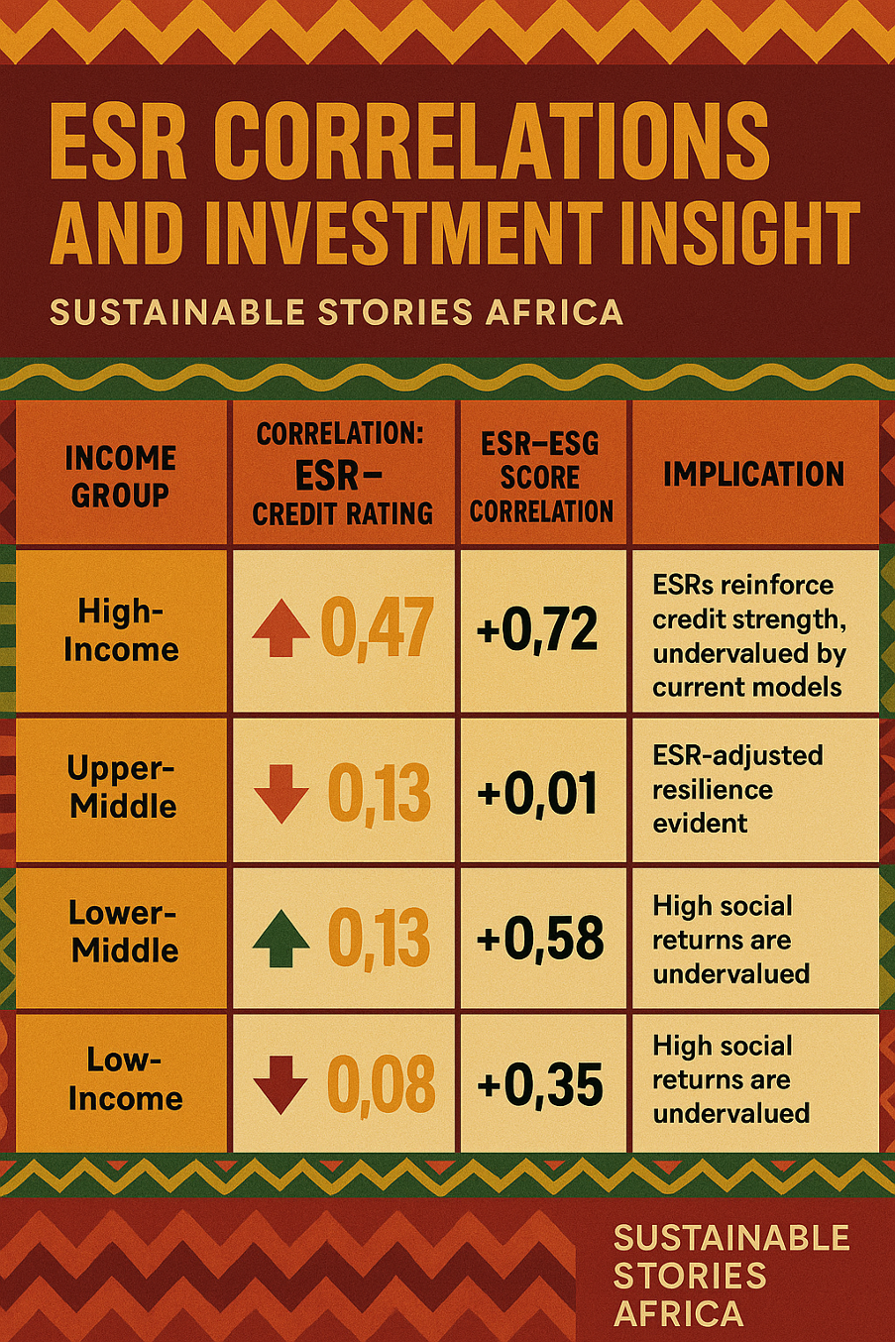

The World Bank's analysis of the HRMI Economic and Social Rights Dataset, which is now integrated into its Sovereign ESG Data Portal, reveals that ESR-adjusted scores capture nuances missed by credit ratings. In low-income countries, the correlation between ESR and credit ratings is negative, meaning that many socially progressive countries are undervalued by current market assessments.

This insight reframes human rights not as political abstractions but as investment intelligence. By evaluating how countries utilise their resources, investors gain a clearer view of institutional quality, policy efficiency, and long-term debt sustainability.

For example, South Africa and Brazil, two upper-middle-income nations compared in the study, show divergent ESR paths. Despite similar GDP profiles, South Africa's stronger rights-based policies correlate with more resilient debt dynamics. The implication? Social progress can be a leading indicator of financial health.

ESR Correlations and Investment Insight

| Income Group | Correlation: ESR–Credit Rating | ESR–ESG Score Correlation | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Income | +0.47 | +0.72 | ESRs reinforce credit strength |

| Upper-Middle | –0.13 | +0.01 | Undervalued by current models |

| Lower-Middle | +0.13 | +0.58 | ESR-adjusted resilience evident |

| Low-Income | –0.08 | +0.35 | High social returns are undervalued |

Investing in Dignity, Measuring Stability

The promise of ESR-driven investing is both moral and material. For Africa's rising markets, it could unlock fairer access to finance, thereby aligning investor returns with inclusive growth outcomes.

An ESR-tilted index, as proposed in the World Bank report, reallocates bond portfolio weights toward countries demonstrating efficient social spending relative to income. This rewards nations like Namibia, Kenya, and Ghana, which have invested in health and education despite fiscal strain, over those with higher GDPs but weaker human rights performance.

Such a model democratises capital. It shifts investor focus from raw income to impact efficiency. How well governments translate each dollar into dignity. As Anne-Marie Brook of the Human Rights Measurement Initiative noted, "Countries that invest in their people build financial trust faster than those that rely on extractive growth."

Redesigning Africa's Sovereign ESG Map

The call to action is clear: integrate human rights data into sovereign investment decisions.

African debt managers, ESG funds, and policymakers must collaborate to ensure the continent's sustainability narratives are backed by measurable social outcomes. This involves:

- Mainstreaming ESR indicators in national budget planning.

- Aligning sovereign bond issuances with social rights targets.

- Partnering with ESR data providers like HRMI for transparency.

- Engaging investors to adopt ESR-tilted indices in Africa-focused portfolios.

For multilateral lenders and rating agencies, it's a wake-up call. As global ESG norms evolve, Africa's voice must shape how "sovereign sustainability" is defined not as a postscript to economic growth, but as its foundation.

Capital, Rights, and Resilience

Africa's next debt era must reward responsibility — not just repayment. By embedding Economic and Social Rights into the fabric of sovereign financing, the continent can shift from reactive borrowing to proactive sustainability.

The World Bank's insight shows the path: human rights are not moral luxuries but measurable predictors of long-term fiscal health. For Africa, that may be the most equitable investment strategy of all.