Africa's fight for fair credit ratings is entering a new phase. As sovereign ESG investing rises, a quiet bias still lurks that wealthier countries score higher, even when poorer nations outperform them on sustainability efforts.

The World Bank's Demystifying Sovereign ESG calls for a radical rethink, one that puts development realities, not income privilege, at the heart of sovereign creditworthiness.

Unmasking Bias in Sovereign ESG Scores

In the evolving architecture of sustainable finance, one uncomfortable truth persists: global ESG ratings are not built for equality.

According to the World Bank's Demystifying Sovereign ESG, sovereign sustainability scores are deeply correlated with income levels—rewarding wealth rather than performance. This "ingrained income bias" systematically undervalues African economies that achieve more with less, while inflating the ratings of richer peers with weaker policy efficiency.

The implications are profound. When the cost of borrowing rises for reasons unrelated to governance or environmental action, entire regions face higher debt burdens. For African governments already navigating climate vulnerability and post-COVID fiscal strain, this flawed metric system locks them into an unequal playing field.

When Wealth Masquerades as Sustainability Strength

The Demystifying Sovereign ESG report's central finding is striking: sovereign ESG scores track income, not impact.

Across six major data providers - MSCI, FTSE Russell, Robeco, Sustainalytics, V.E (Moody's), and RepRisk, the World Bank found that average correlations between sovereign ESG scores and national income (GNI per capita) range from 58% to 85%.

The Environmental (E) pillar is the most inconsistent, while the Social (S) and Governance (G) pillars show higher alignment, but still skew upward with income. This means that poorer nations, no matter how progressive their policies, are structurally rated lower.

"Sovereign ESG scores are converging not because countries are performing similarly, but because income dominates the model," the report notes.

For investors, this distortion means ESG data often reinforces—not corrects—global financial inequality.

Correlation Between ESG Scores and National Income

ESG Provider | Correlation with GNI per Capita | Most Biased Pillar | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

FTSE Russell / Beyond Ratings | 69.8% | Environmental | High-income skew |

MSCI | 83.2% | Governance | Penalises frontier markets |

Robeco | 85.2% | Social | Over weights institutional maturity |

Sustainalytics | 72.0% | Environmental | Favours developed economies |

V.E (Moody’s) | 58.5% | Environmental | Moderate bias, mixed transparency |

RepRisk | 70.5% | Governance | Reputational tilt |

Inside the Mechanics of Sovereign ESG Scoring

The sovereign ESG ecosystem, mapped in the report's "financial ecosphere," is a dense web of issuers, data providers, investors, and regulators. But it's also one marked by methodological opacity.

Unlike corporate ESG, where divergence between rating agencies is well documented, sovereign ESG shows convergence, which is not driven by accuracy but by common bias.

Most providers use overlapping datasets such as the Yale Environmental Performance Index (EPI), the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index (ND-GAIN), and the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), all of which correlate strongly with income.

As a result, African countries are trapped in a feedback loop: weak data access → lower ratings → higher borrowing costs → less fiscal space to improve real ESG outcomes.

A parallel study by Morgan Stanley Investment Management (2019) found that standard ESG scores systematically penalise developing countries, proposing an income- and momentum-adjusted approach as a remedy.

The ESG Ecosphere – A circular system built on unequal data foundations

A circular diagram showing:

- Core: Sovereign Issuer (Government)

- Middle ring: ESG Data Providers (MSCI, V.E, Robeco, Sustainalytics)

- Outer ring: Credit Rating Agencies, Asset Managers, Institutional Investors.

- Regulatory layer: OECD, UN, WBG

Redefining Fairness in ESG Ratings

The opportunity lies in decoupling sustainability from wealth.

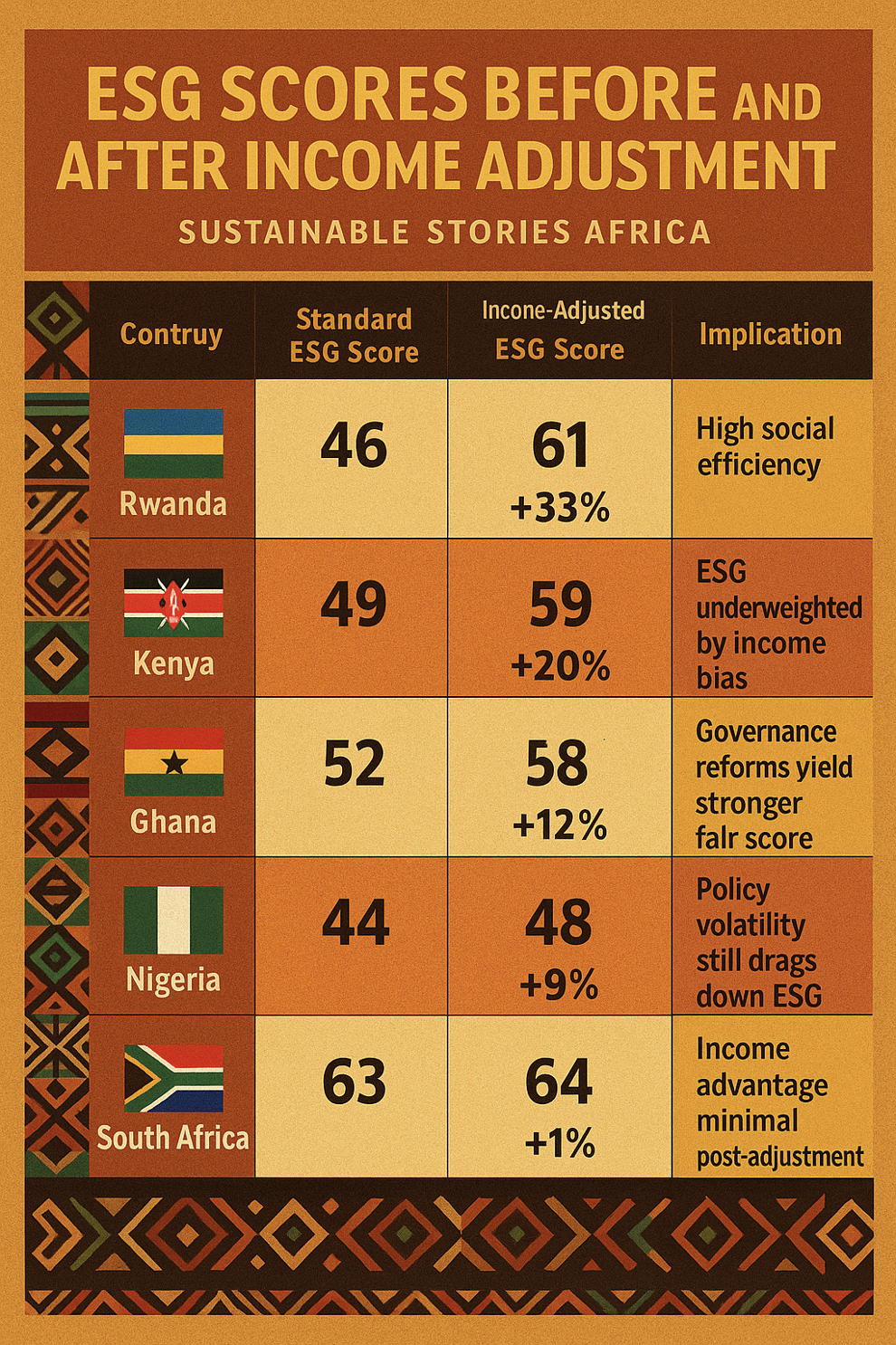

World Bank researchers propose an income-adjusted methodology that neutralises the GDP effect and instead rewards the efficiency of policy delivery. In this model, low-income countries that achieve high outcomes per resource unit, such as Rwanda or Namibia, gain the recognition they deserve.

When adjusted for income, the gap between African and OECD ESG scores narrows dramatically. Frontier markets that demonstrate resilience and reform see improved sustainability profiles, providing investors with a more authentic signal of long-term stability.

As the report notes: "Adjusting for national income transforms ESG from a mirror of wealth into a measure of effort."

For Africa, this shift could mean lower borrowing costs, greater access to sustainable capital, and a more just global financial order.

ESG Scores Before and After Income Adjustment

Country | Standard ESG Score | Income-Adjusted ESG Score | Change (%) | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Rwanda | 46 | 61 | +33% | High social efficiency |

Kenya | 49 | 59 | +20% | ESG underweighted by income bias |

Ghana | 52 | 58 | +12% | Governance reforms yield stronger fair score |

Nigeria | 44 | 48 | +9% | Policy volatility still drags down ESG |

South Africa | 63 | 64 | +1% | Income advantage minimal post-adjustment |

Building Africa's Sovereign ESG Identity

Africa cannot wait for global rating agencies to correct course. Regional institutions from the African Development Bank to the African Union's Green Recovery Action Plan must pioneer an African-led sovereign ESG framework that accounts for development realities and local data contexts.

This means:

- Developing open ESG data repositories aligned with continental benchmarks.

- Embedding income-adjusted scoring into green bond certifications.

- Collaborating with global ESG providers for methodology transparency.

- Training African financial analysts in sovereign sustainability assessment.

The World Bank's call for "transparency, forward-looking data, and local adaptation" offers a foundation; however, Africa's financial sovereignty depends on localising those principles.

Equity, Effort, and Sustainable Sovereignty Ahead

To make ESG truly fair, methodologies must measure effort, not affluence. For Africa, this means replacing external bias with local credibility, and redefining sovereign sustainability as the capacity to thrive within constraints.

By investing in transparent data, regional frameworks, and income-adjusted models, African nations can transform ESG from a gatekeeper into a gateway, one that finally reflects their real value in a changing financial world.