Not all public investment reduces debt. Some of it quietly increases sovereign risk.

A new World Bank index shows that infrastructure spending lowers borrowing costs only in countries where project quality is high.

For much of Africa, the difference between growth and debt distress lies in the quality of spending rather than the volume.

Africa's Infrastructure Choice: Efficiency Or Exposure

Across Africa, governments face the same dilemma: vast infrastructure gaps, limited fiscal space, and rising sovereign spreads. The instinct is clear: invest more. Build roads, ports, power plants, and schools.

However, the World Bank's research delivers a harsher reality. Public investment can be self-financing only when it is efficient.

Using a Public Investment Quality (PIQ) index extrapolated from 4,600 evaluated World Bank projects across 120 countries (2000–2021), the authors show that the same increase in capital spending can either reduce sovereign risk or worsen debt dynamics, depending on quality.

For Africa, where infrastructure needs are acute and debt vulnerabilities elevated, this distinction is not academic. It is existential.

Spending More Is Not Enough

The headline finding is stark.

High levels of public investment are associated with lower sovereign risk in countries with high investment quality, whilst higher sovereign risk is associated with low investment quality.

In simple terms:

- Good projects can pay for themselves.

- Poor projects compound debt.

The mechanism operates through the classic debt dynamics equation: debt sustainability depends on the relationship between growth (g), interest rates (r), and the primary balance.

High-quality improves long-term growth and reduces borrowing costs. Low-quality investments increase expenditure without lifting productivity, worsening fiscal fundamentals.

For African policymakers juggling infrastructure ambitions and IMF debt sustainability analyses, this is the difference between convergence and crisis.

What the Numbers Reveal

The PIQ index measures de facto project outcomes, not procedures, using standardised six-point project performance ratings from the World Bank's Independent Evaluation Group.

The index controls for project size, supervision, entry quality, and macroeconomic conditions, isolating country-level public investment performance.

Three patterns stand out:

- Low-income countries (LICs) score significantly lower on public investment quality.

- Commodity-exporting economies tend to exhibit lower PIQ scores; consistent with the "paradox of plenty."

- The gap between stronger and weaker performers has widened over time.

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) lags most other EMDE regions on average, though heterogeneity remains substantial.

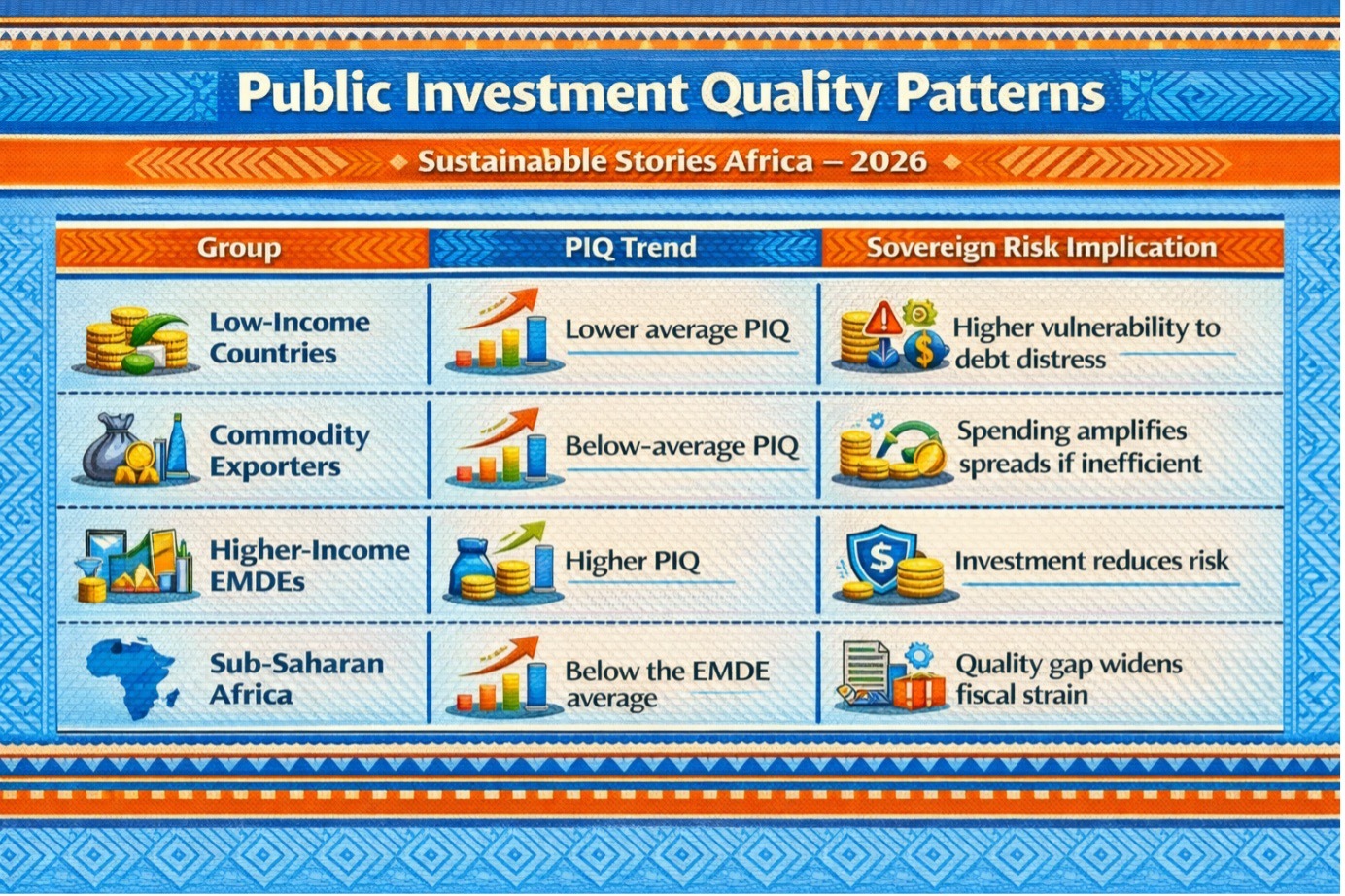

Public Investment Quality Patterns

| Group | PIQ Trend | Sovereign Risk Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Income Countries | Lower average PIQ | Higher vulnerability to debt distress |

| Commodity Exporters | Below-average PIQ | Spending amplifies spreads if inefficient |

| Higher-Income EMDEs | Higher PIQ | Investment reduces risk |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | Below the EMDE average | Quality gap widens fiscal strain |

The fiscal transmission is quantifiable.

A one-standard-deviation increase in public investment is associated with:

- A 3-notch downgrade in sovereign ratings in the lowest-PIQ countries.

- Nearly a 4-notch upgrade in the highest-PIQ countries.

The same spending, radically different outcomes. The effect is strongest in sub-investment-grade countries, precisely where many African economies sit.

What High-Quality Investment Changes

If quality improves, public investment becomes a growth accelerator rather than a fiscal liability.

The research shows that when PIQ is high:

- Public investment reduces CDS spreads.

- Debt-to-GDP ratios decline over time.

- Borrowing costs ease.

In effect, high-quality investment can "fund itself."

In contrast, a low-quality investment:

- Increases debt ratios.

- Raises sovereign spreads.

- Weakens fiscal credibility.

For African economies facing Eurobond maturities and refinancing pressures, this distinction shapes market perception.

A finance minister in West Africa recently put it bluntly: "Investors don't just ask how much we are borrowing. They ask what we are building and whether it works."

Quality is now priced into risk.

Investment Quality and Debt Outcomes

| Investment Quality | Growth Effect | Interest Rate Effect | Long-Term Debt Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| High PIQ | Boosts productivity | Lowers spreads | Debt ratio declines |

| Low PIQ | Weak growth multiplier | Raises spreads | Debt ratio increases |

The numbers reframe the infrastructure debate. It is not "invest or consolidate." It is "invest well or risk insolvency."

Three Shifts for African Policymakers

The policy implications are clear and urgent.

Prioritise Project Appraisal Over Volume

– Strengthen ex-ante appraisal, cost-benefit analysis, and independent evaluation systems. Quantity cannot substitute for quality.

Monitor Lifecycle Performance

– Track projects from appraisal to implementation and maintenance. Weak maintenance erodes returns and debt sustainability.

Align Debt Strategy With PIQ Reform

– Before scaling investment, upgrade procurement systems, transparency, and institutional capacity.

The research explicitly calls for enhanced technical assistance and concessional support for low-income countries struggling with weak public investment management.

For African governments, concessional finance tied to project governance reform may offer the safest path to scaling.

Markets are already distinguishing. Countries that improve institutional quality reduce spreads even before GDP accelerates.

PATH FORWARD – Quality Before Quantity, Growth Before Debt

Africa's infrastructure needs are undeniable. However, the evidence is equally clear: high-quality public investment strengthens fiscal sustainability; low-quality spending, on the other hand, deepens risk.

The next infrastructure cycle must embed stronger project evaluation, governance reform, and debt management frameworks. When quality improves, investment becomes a tool for convergence, not a trigger for crisis.