Low- and middle-income countries are under pressure to create millions of jobs annually; however, formal employment lags labour force growth.

A World Bank guidebook distils evidence from over 100 rigorously evaluated programs showing that well-designed labour market interventions can raise earnings by up to five times the average impact.

The message is clear: employment solutions work, but only when they are tailored, integrated and aligned with market realities.

Jobs Gap Demands Smarter Solutions

Each year, millions of young people in low- and middle-income countries enter labour markets that are not creating enough quality jobs. Formal wage employment is failing to keep pace with demographic expansion.

In low-income countries, nearly nine working-age individuals enter the labour force for every new wage job created.

At the same time, informality remains stubbornly high, youth unemployment persists, and women’s labour force participation shows limited structural progress.

Growth and educational attainment have improved, but employment outcomes have not kept up.

A World Bank guidebook, What Works for Work, argues that the problem is not a lack of tools. It is a matter of design, context, and execution.

Proven Programs Deliver Outsized Impacts

The evidence is striking.

A meta-analysis of 102 randomised controlled trials finds that the best employment programs generate impacts three to five times larger than the average intervention.

The top 10% of programs show employment gains nearly 4.8 times above average, and earnings gains 3.8 times higher.

Contrary to common scepticism, labour market programs are more effective in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income ones.

Youth-focused interventions in LMICs deliver impacts roughly twice as strong as comparable programs in advanced economies.

Impact is not theoretical. In Bangladesh, a vocational training program, the “Plus” program”, increased earnings by 304%.

In North Macedonia, a wage subsidy program increased employment by 87% and income by 93%.

Uganda’s Women’s Income Generating Support program increased employment by 103%.

The message: results at scale are possible.

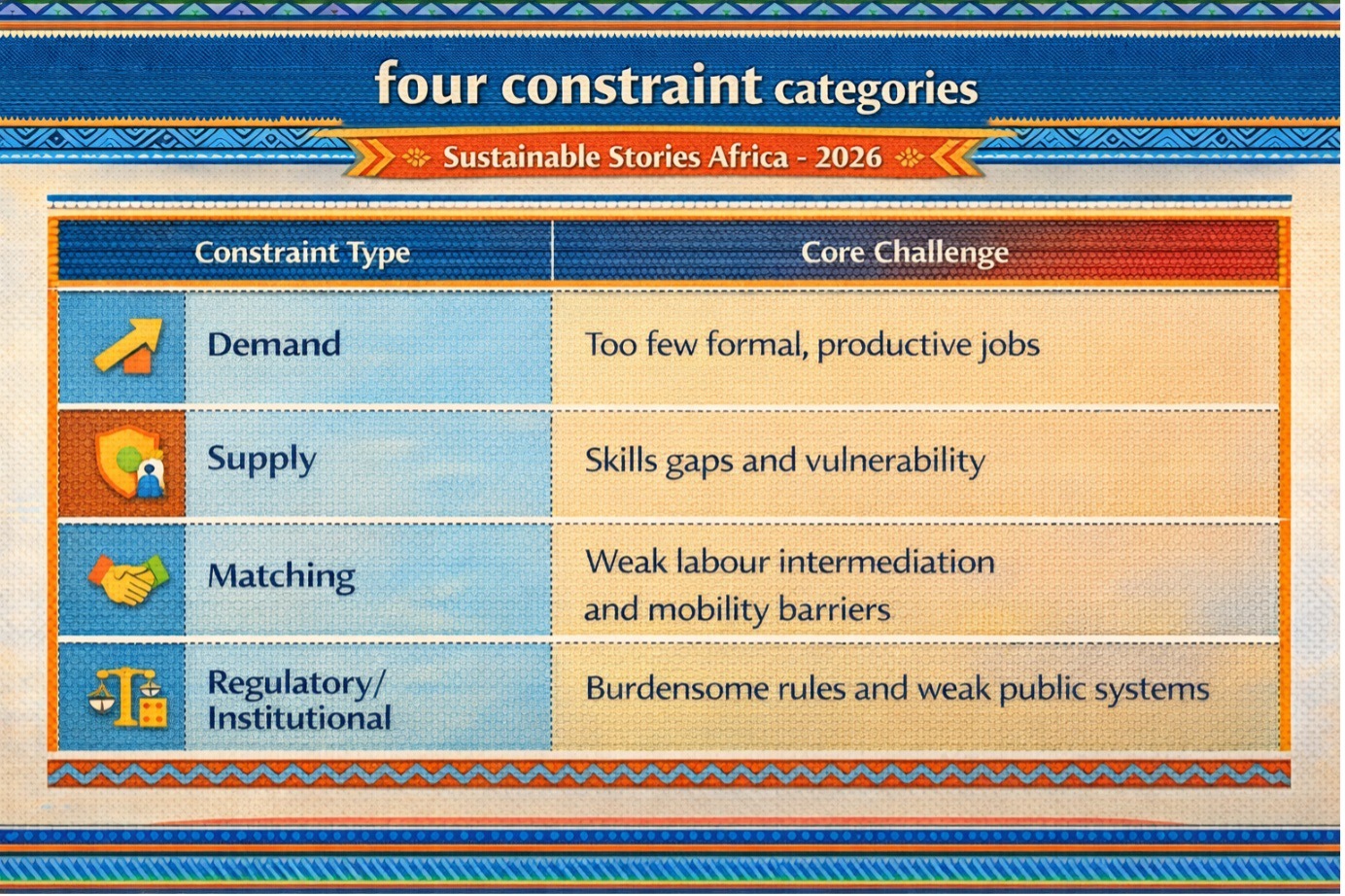

Diagnosing the Real Constraints

The guidebook structures the employment challenge around four constraint categories:

Constraint Type | Core Challenge |

|---|---|

Demand | Too few formal, productive jobs |

Supply | Skills gaps and vulnerability |

Matching | Weak labour intermediation and mobility barriers |

Regulatory/Institutional | Burdensome rules and weak public systems |

In low-income countries, up to 71% of workers are undereducated for their jobs. Only 25% of firms in low-income countries have formal training, compared to 41% in high-income countries.

Meanwhile, informal recruitment dominates. In many middle-income economies, firms rely heavily on personal networks rather than public employment services, limiting access for marginalised groups.

Infrastructure compounds the problem. Where rural road access is weak, informality is higher.

Mobility constraints and migration costs, sometimes equivalent to one year’s wages, prevent workers from relocating to areas of opportunity.

However, the evidence shows these constraints are not destiny. Programs that address them systematically can move labour markets.

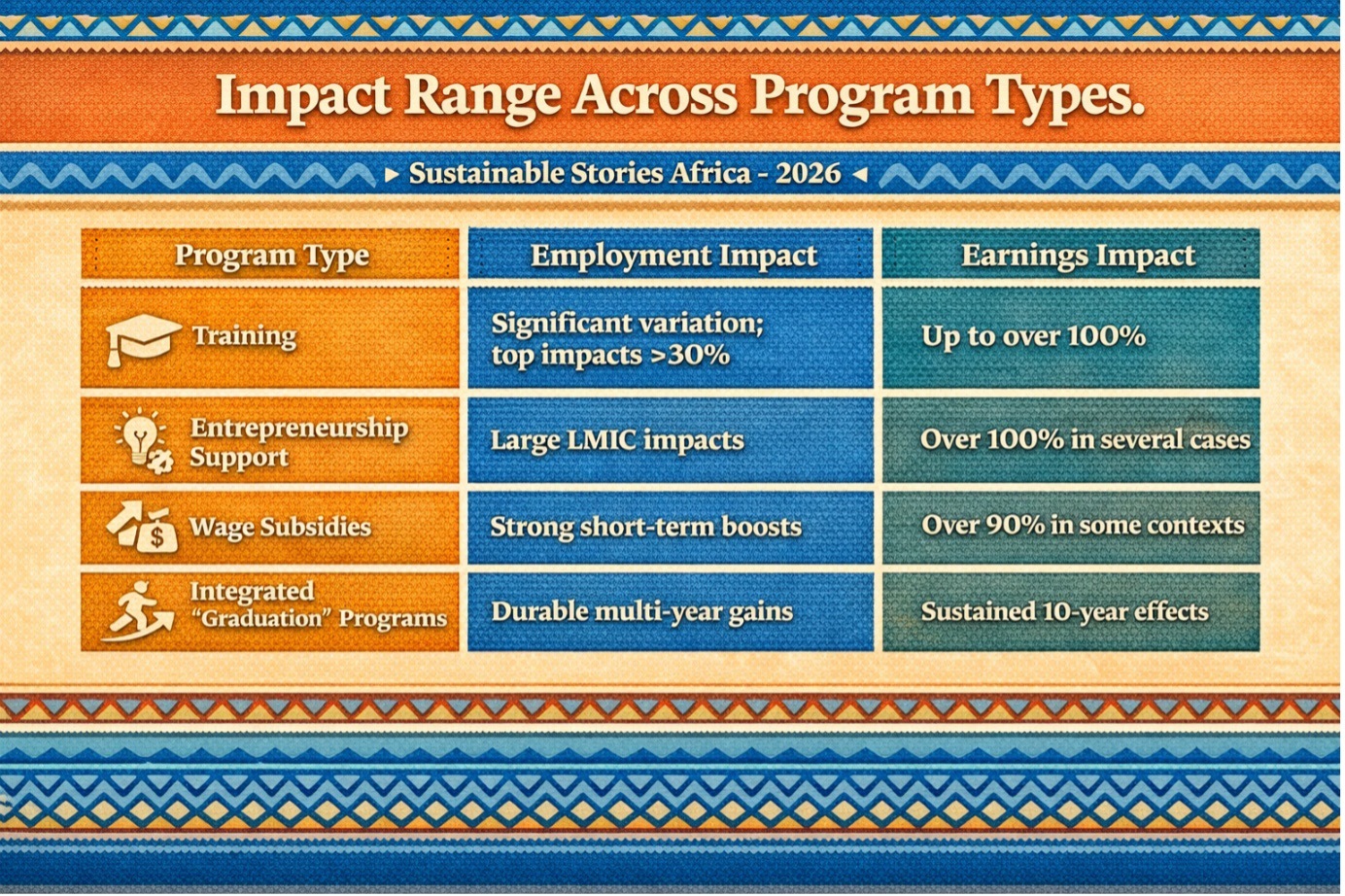

Impact Range Across Program Types

Program Type | Employment Impact | Earnings Impact |

|---|---|---|

Training | Significant variation; top impacts >30% | Up to over 100% |

Entrepreneurship Support | Large LMIC impacts | Over 100% in several cases |

Wage Subsidies | Strong short-term boosts | Over 90% in some contexts |

Integrated “Graduation” Programs | Durable multi-year gains | Sustained 10-year effects |

Design Principles That Multiply Impact

The guidebook distils five design principles that separate high-performing programs from mediocre ones:

- Tailor to context and worker profile: – Interventions must respond to whether workers face high opportunity, high readiness, or low opportunity, low readiness environments.

- Be comprehensive and cross-sectoral: – Programs combining training, mentorship, and capital support outperform single-component models.

- Align incentives: – Performance-based contracts for providers and monetary incentives for participants increase engagement and outcomes.

- Engage the private sector: – Employer involvement ensures skill relevance and improves hiring conversion.

- Integrate with social protection: – Linking employment services with income support enhances participation among vulnerable groups.

The payoff can be substantial.

Kenya’s Youth Employment and Opportunities Project cost $374 per beneficiary and generated annual earnings gains of $387, recouping costs within 10 months.

Ethiopia’s graduation program, though more expensive at $1,249 per participant, generated long-term returns exceeding $10,000 in PPP-adjusted benefits.

Even in fragile settings, programs can be effective. In Afghanistan, a graduation intervention program produced a 32% increase in income after five years. In Côte d’Ivoire’s post-conflict areas, formal apprenticeships raised youth earnings by 15% four years later.

These are not pilot curiosities. They are scalable models.

From Diagnosis to Scaled Solutions

The guidebook proposes a structured eight-step framework:

- Define the target group

- Diagnose binding constraints

- Map opportunity–readiness profiles

- Engage employers

- Select proven interventions

- Integrate complementary supports

- Align incentives

- Pilot, learn, and scale

This sequencing moves policy from aspiration to institutionalised reform.

Governments facing shrinking fiscal space cannot afford trial-and-error programming. Evidence-based employment strategies offer both short-term gains and long-term structural dividends.

The choice is no longer whether labour market programs work. The question is whether policymakers will adopt what works.

PATH FORWARD – Scale Evidence, Align Incentives

The priority now is institutionalisation. Governments must embed diagnostic frameworks into national job strategies, ensure cost-benefit assessments accompany program rollout, and align employment services with private-sector demand.

If scaled thoughtfully, employment solutions can transform demographic pressure into productive opportunity. The tools exist.

The next step is disciplined execution, anchored in data, incentives, and context-sensitive design.