The world economy is heading toward its weakest long-term growth stretch in three decades.

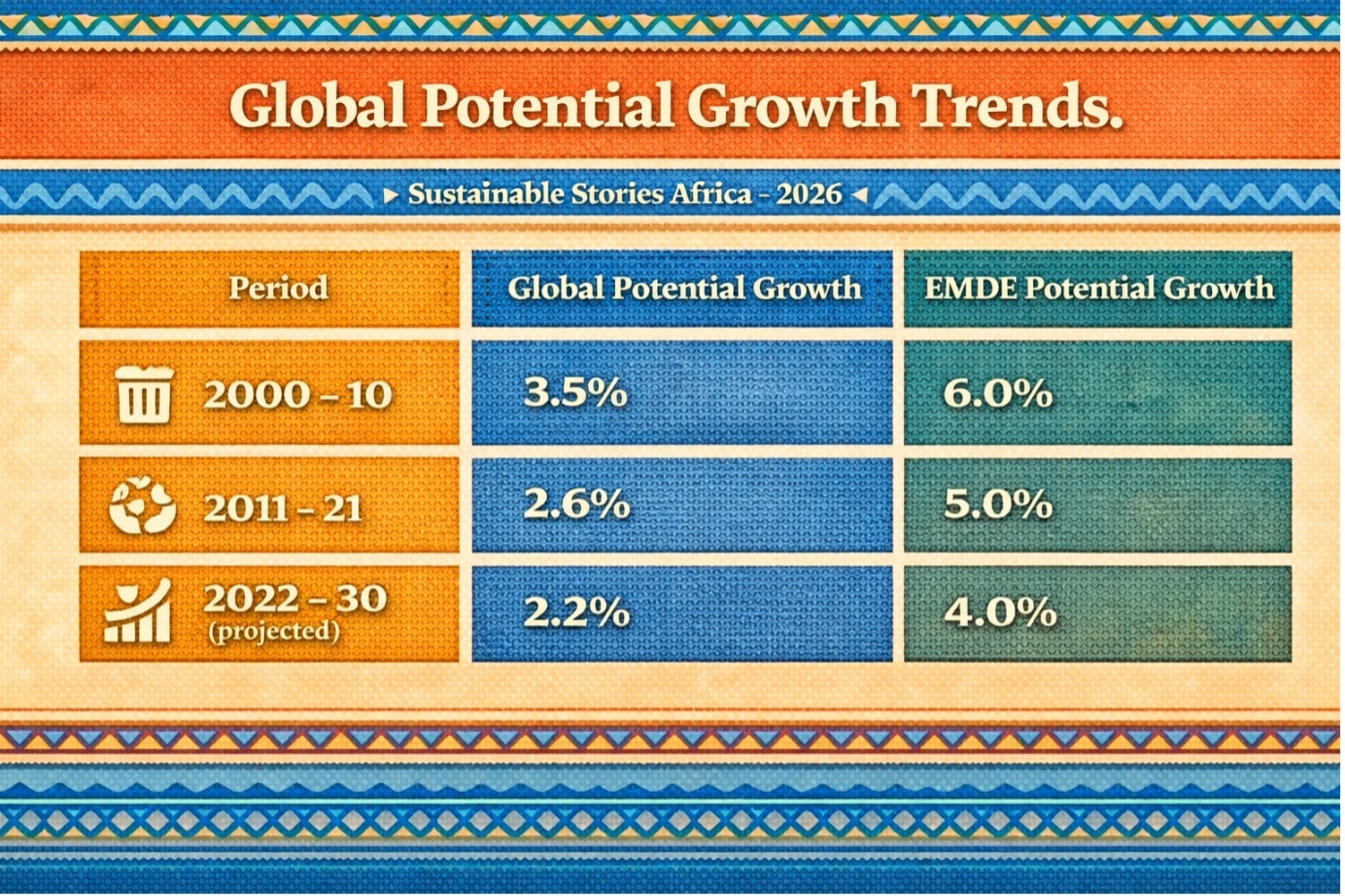

According to the World Bank’s report Falling Long-Term Growth Prospects, potential global GDP growth could slow to just 2.2% annually through 2030, down sharply from 3.5% in the early 2000s.

For emerging markets, the slowdown is deeper still. Investment, productivity and labour-force growth, once reliable engines of convergence, are all losing momentum, threatening poverty reduction, climate goals and fiscal stability.

Lost Decade Looms for Global Growth

The global economy is approaching a structural turning point. Growth is no longer merely cyclical; it is steadily decelerating at its core.

The World Bank’s latest flagship analysis (Pages 55 – 225) warns that potential GDP growth, the economy’s “speed limit”, is on track to fall to a three-decade low of 2.2% annually through 2030, down from 2.6% between 2011 and 2021 and 3.5% between 2000 and 2010.

This is not a temporary dip. It is a broad-based slowdown affecting advanced economies and emerging markets. 80% of advanced economies and 75% of EMDEs grew more slowly between 2011 and 2021 than between 2000 and 2010.

The implications stretch beyond GDP figures. Slower growth weakens poverty reduction, limits fiscal space, constrains climate financing and risks undermining debt sustainability. The question now is not whether growth is slowing; it is how governments respond.

A Structural Slowdown Takes Hold

The numbers are stark. Global growth declined from 4.5% in 2010 to a projected 1.7% in 2023.

Emerging markets and developing economies, once the drivers of global expansion, have seen potential growth decline from 6% between 2000 and 2010 to 5% between 2011 and 2021, and a further decline to 4% this decade.

The report concludes unequivocally: the slowdown is structural, not temporary. Productivity growth is weakening. Investment growth has halved compared to the previous two decades. Working-age population growth has declined in the last three decades. In short, the engines of prosperity are sputtering simultaneously.

What Is Driving the Weakness?

The report identifies four interlinked drivers behind the slowdown:

- Investment Deceleration: – Investment growth in EMDEs is projected at just 3.5% annually, roughly half the recorded average of between 2000 and 2021. Weak capital formation dampens productivity and future output.

- Total Factor Productivity (TFP) Weakness: – TFP growth is expected to record its slowest pace since 2000. Technological diffusion, innovation, and factor reallocation have all slowed.

- Demographic Headwinds: - The growth of the global labour force has decelerated sharply. Ageing populations in advanced economies and slowing workforce expansion in EMDEs constrain output potential.

- Trade Stagnation: - From the 1990s to 2011, trade growth was twice as fast as GDP. Today, it barely aligns with the output growth. Trade costs, logistics frictions, and rising policy uncertainty are weighing on the level of integration.

The cumulative effect? Slower income convergence. Between 2000 and 2010, EMDE per capita income growth exceeded that of advanced economies by 3.4 percentage points annually. Between 2011 and 2021, that gap narrowed to 2.0 percentage points.

That erosion matters for Africa and other developing regions seeking structural transformation.

Global Potential Growth Trends

Period | Global Potential Growth | EMDE Potential Growth |

|---|---|---|

2000 – 10 | 3.5% | 6.0% |

2011 – 21 | 2.6% | 5.0% |

2022 – 30 (projected) | 2.2% | 4.0% |

The Policy Upside Scenario

The report does not end in a gloomy path. It outlines a coordinated reform push capable of lifting potential global growth by 0.7 percentage points, raising it to roughly 2.9% annually.

The six priority levers include:

- Increasing investment, particularly climate-aligned infrastructure

- Strengthening macroeconomic frameworks

- Cutting trade costs

- Capitalising on services-led growth

- Boosting labour force participation, especially among women

- Strengthening global cooperation

Notably, raising female labour force participation to match the best historical 10-year gains could lift global potential growth by 0.2 percentage points by 2030.

Climate-aligned investments alone could increase growth potential by as much as 0.3 percentage points annually while enhancing resilience.

The message is clear: reform dividends exist, but they require synchronised action.

A Coordinated Push or a Lost Decade

The report frames the moment as a crossroads. Without decisive reform, the 2020s risk becoming a “lost decade” for global development.

Governments must replicate their most significant historical reform episodes, improving business climates, deepening financial markets, investing in human capital, and aligning fiscal and monetary policy.

For emerging markets, especially across Africa, the imperative is sharper: slower potential growth constrains poverty reduction, debt repayment capacity and climate adaptation financing.

This is not simply about raising GDP. It is about preserving development momentum. The policy window remains open but is narrowing.

Path Forward – Coordinated Reforms to Restore Global Growth

Reviving long-term growth requires a coordinated investment push grounded in macroeconomic stability, institutional reform and climate-aligned capital deployment.

Governments are being urged to strengthen trade facilitation, expand female labour participation, and modernise services sectors to unlock productivity gains.

If implemented collectively, these reforms could enable global potential growth of 0.7 percentage points by 2030, reversing the structural slowdown and restoring development momentum.