The world spends up to $143 billion annually protecting biodiversity, but needs as much as $967 billion to halt ecosystem collapse by 2030.

The resulting financing gap, estimated to be between $598 and $824 billion annually, exposes a structural mismatch between environmental ambition and capital allocation.

A landmark report, Financing Nature, argues the gap is large but solvable. Reforming harmful subsidies, mobilising private capital, and scaling innovative financial mechanisms could unlock up to $632 billion annually by the end of the decade.

Nature’s $711 Billion Financing Gap

The global economy depends on nature far more than markets currently recognise.

However, funding to protect biodiversity remains drastically insufficient. According to Financing Nature: Closing the Global Biodiversity Financing Gap, current global biodiversity finance totals between $124 and $143 billion annually, while estimated needs reach between $722 and $967 billion per year by 2030.

The resulting annual shortfall, between $598 and $824 billion, means only between 16% and 19% of the required funding is currently mobilised.

More striking still: governments spend between $274 and $542 billion annually on subsidies that are harmful to biodiversity, which is two to four times more than total conservation spending.

The imbalance represents a central conclusion of the report: biodiversity loss is not merely an ecological crisis; it is a failure of capital allocation.

Biodiversity Loss Threatens Global Economic Stability

Nature is economic infrastructure.

The report cites research estimating that $44 trillion of global GDP, representing over half of world output, is moderately or highly dependent on nature.

Other indicators underscore systemic exposure:

- Pollinator loss could reduce agricultural output by $217 billion annually

- Forest carbon sinks alone may hold an implied economic value exceeding $100 trillion

- One-third of pharmaceuticals originate from natural compounds

However, biodiversity finance remains fragmented, underpriced, and politically marginalised.

Without reform, ecosystem degradation risks becoming a macroeconomic shock.

Conservation Finance Covers Only 19%

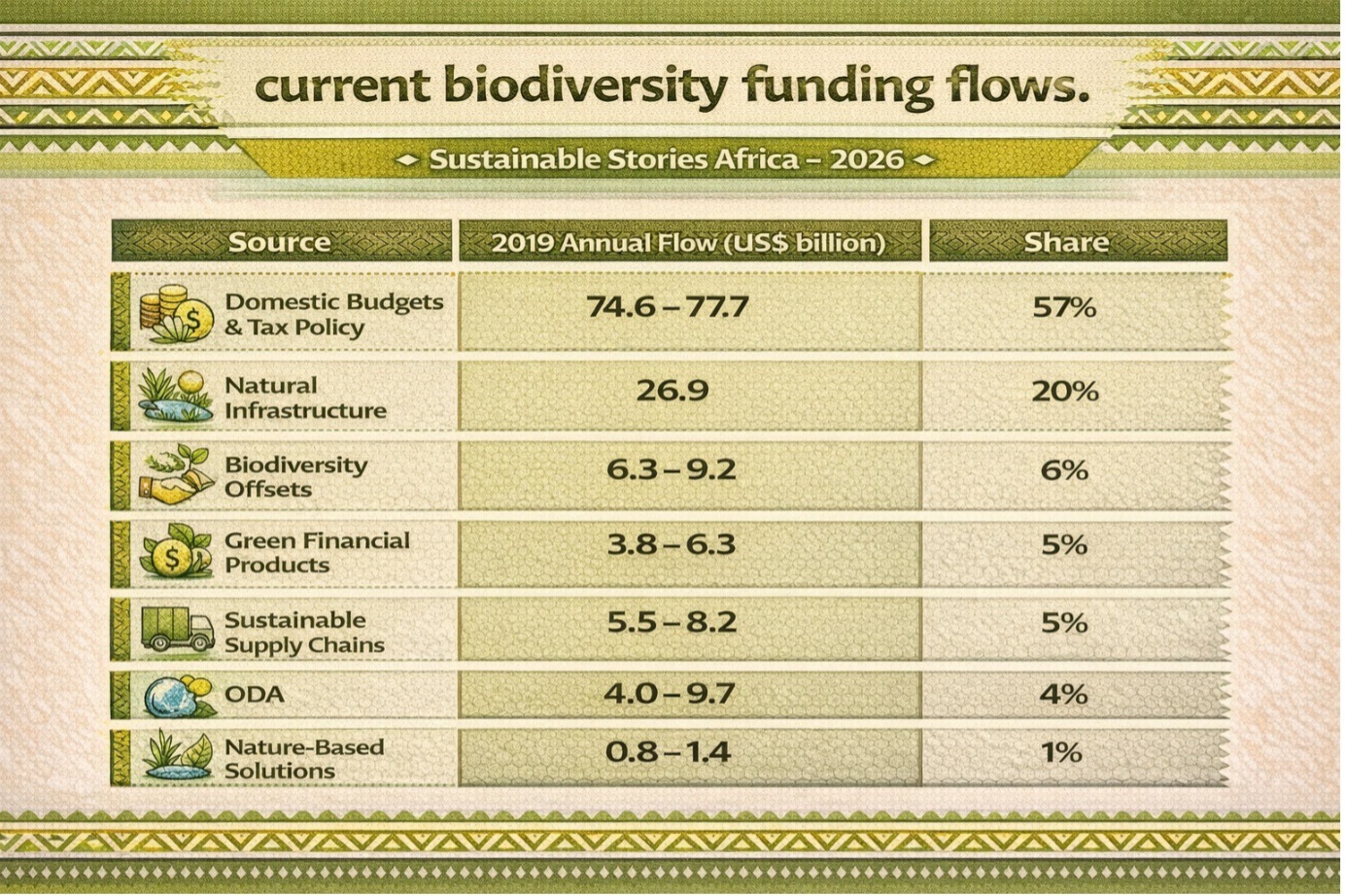

The report disaggregates current biodiversity funding flows:

Source | 2019 Annual Flow (US$ billion) | Share |

|---|---|---|

Domestic Budgets & Tax Policy | 74.6 – 77.7 | 57% |

Natural Infrastructure | 26.9 | 20% |

Biodiversity Offsets | 6.3 – 9.2 | 6% |

Green Financial Products | 3.8 – 6.3 | 5% |

Sustainable Supply Chains | 5.5 – 8.2 | 5% |

ODA | 4.0 – 9.7 | 4% |

Nature-Based Solutions | 0.8 – 1.4 | 1% |

Total: $124 – $143 billion

Projected needs by 2030 include:

- Cropland transition to conservation agriculture: $315 – $420 billion

- Protected areas (30% target): $149 – $192 billion

- Rangeland reform: $81 billion

- Urban water safeguards: $73 billion

- Fisheries transition: $23 – $47 billion

Aggregate need: Between $722 and $967 billion annually (between 0.7 and 1.0% of global GDP)

The scale is daunting; however, it is not unprecedented. Climate finance reached $579 billion annually between 2017 and 2018, according to a comparative analysis cited in the report.

Nine Mechanisms Can Unlock Capital

The report identifies nine financial and policy mechanisms capable of mobilising between $446 and $633 billion annually by 2030.

Key levers:

- Harmful Subsidy Reform – Phasing out biodiversity-damaging agricultural, forestry, and fishery subsidies could reduce annual harmful flows by up to $268 billion.

- Biodiversity Offsets – Scaling global offset implementation could grow from $6 to $9 billion today and between $162 and $168 billion by 2030.

- Natural Infrastructure – Watershed protection and ecosystem service investments could increase from $27 billion to between $105 and $139 billion.

- Green Financial Products – Sustainability-linked instruments could scale to between $31 and $92 billion annually.

- Nature-Based Solutions & Carbon Markets – Could grow from $1 billion to between $25 and $40 billion annually.

If fully implemented and coupled with subsidy reform, the financing gap narrows substantially.

The report argues this is not unrealistic. The required scale is comparable to global beverage spending annually and within the range of capital markets’ existing liquidity.

Governments Must Catalyse Private Capital

The central insight is unequivocal: governments must lead.

The report’s six overarching recommendations include:

- Double the international biodiversity aid by 2030

- Develop National Biodiversity Finance Plans (NBFPs)

- Reform harmful subsidies immediately

- Strengthen regulatory frameworks to de-risk private investment

- Mandate biodiversity risk disclosure by financial institutions

- Mobilise domestic fiscal tools (earmarked taxes, levies, fees)

The private sector, the report argues, will not deploy capital at scale without appropriate policy architecture.

Philanthropy distributes profits. Investment generates them.

Aligning biodiversity conservation with risk management, regulatory compliance, and long-term value creation is therefore essential.

Path Forward – Subsidy Reform to Fund Nature Now

Closing the biodiversity financing gap requires coordinated subsidy reform, scaled private-sector participation, and mandatory biodiversity risk disclosure frameworks.

Governments must double international biodiversity finance and implement National Biodiversity Finance Plans before 2030.

If the nine mechanisms are fully deployed, up to $632 billion annually could be mobilised. Without subsidy reform, however, a residual gap of between $210 and $239 billion will persist, leaving biodiversity targets structurally underfunded.