Net public finance to developing countries has fallen sharply, even as global crises multiply.

A new analysis by the Development Finance Observatory reveals a 25% decline in net flows over the past decade, driven not only by aid cuts, but by rising debt repayments and a dramatic reversal in Chinese lending.

Multilateral lenders have stepped into the breach. But the data suggests the global development finance architecture is shifting in ways that could redefine Africa’s fiscal future.

The Great Reversal in Global Development Finance

For two decades, development finance flowed steadily into low- and middle-income countries, underwriting investments in health systems, education reform, energy access and infrastructure corridors. That era is ending.

Analysis from the Development Finance Observatory shows that total net flows to low- and middle-income countries declined by 25% between 2010 and 2014, and again between 2020 and 2024.

The drop is not simply about shrinking aid. It reflects rising debt service payments, the collapse of private external lending, and a fundamental reversal in Chinese finance.

The result is a quieter but more consequential shift: developing countries are increasingly financing their futures from constrained domestic budgets, and multilateral institutions are becoming the dominant source of external net support.

A 25% Drop Reshapes Development Finance

The headline figure is stark. The volume of net public external finance available to low- and middle-income countries dropped by a quarter over the past decade.

This decline reflects a widening gap between gross inflows, grants and loans, and the outflows required to service existing debt.

Net flows peaked at $164 billion in 2021 but dropped to $112 billion by 2024, a level not seen since 2012.

However, beneath the aggregate decline lies a divergence:

- Net flows to low- and lower-middle-income countries increased by 14% when upper-middle-income countries are excluded.

- Upper-middle-income countries experienced net negative flows.

This bifurcation suggests heightened vulnerability among middle-income borrowers facing expensive debt service burdens.

China’s Reversal and Private Finance Collapse

The most dramatic shift is what the report calls a “Great Reversal” in China’s finance.

A decade ago, China was a net provider of $48 billion to low- and lower-middle-income countries.

Over the last five years, it has become a net extractor of $24 billion. In 2024 alone, China extracted $12.3 billion, in comparison to every other DAC donor, except the United States.

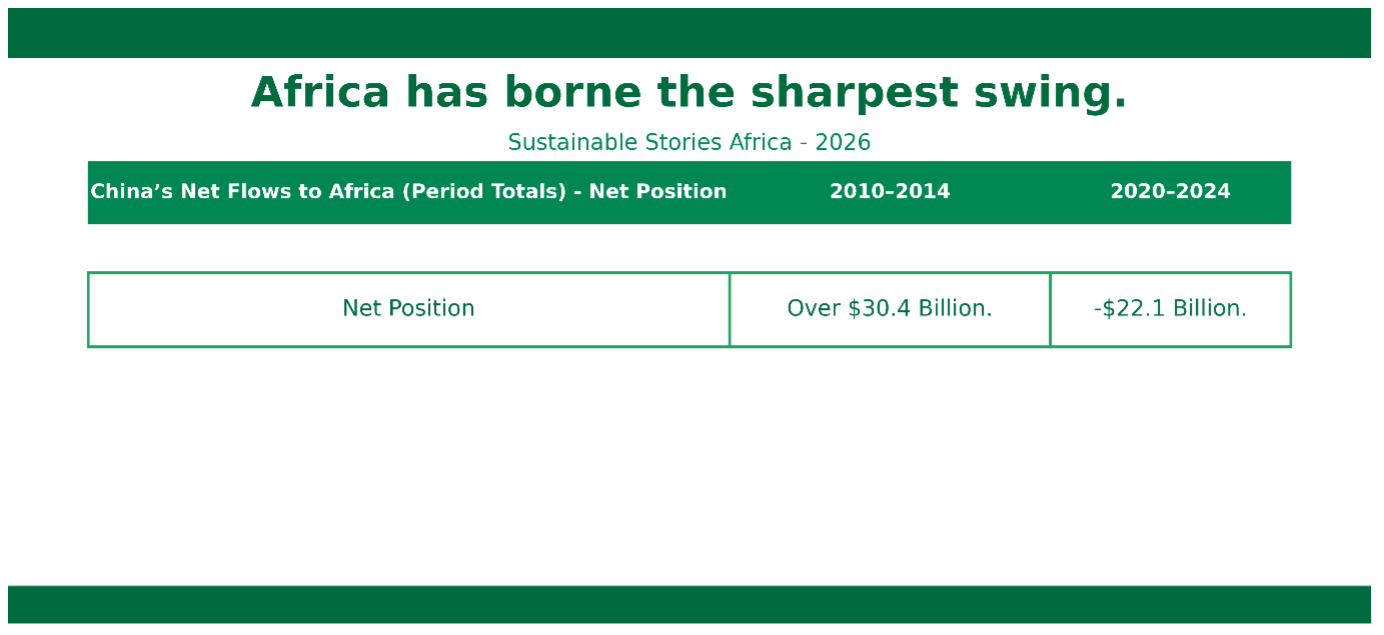

Africa has borne the sharpest swing:

China’s Net Flows to Africa (Period Totals) | 2010–2014 | 2020–2024 |

|---|---|---|

Net Position | Over $30.4 Billion | -$22.1 Billion |

This represents a $52.5 billion reversal.

At the same time, private external public and publicly guaranteed long-term debt collapsed, providing $115 billion in net new resources (2010–2014) to just $7.3 billion in the last five years, falling from 19% of net flows to just 1%.

The composition of development finance has changed as profoundly as the volume.

Multilaterals as the New Bedrock

If one pillar has strengthened amid the retrenchment, it is multilateral finance.

Multilateral institutions, including major multilateral development banks, have increased their financing by 124% and now account for 56% of total net flows, up from 28% a decade ago.

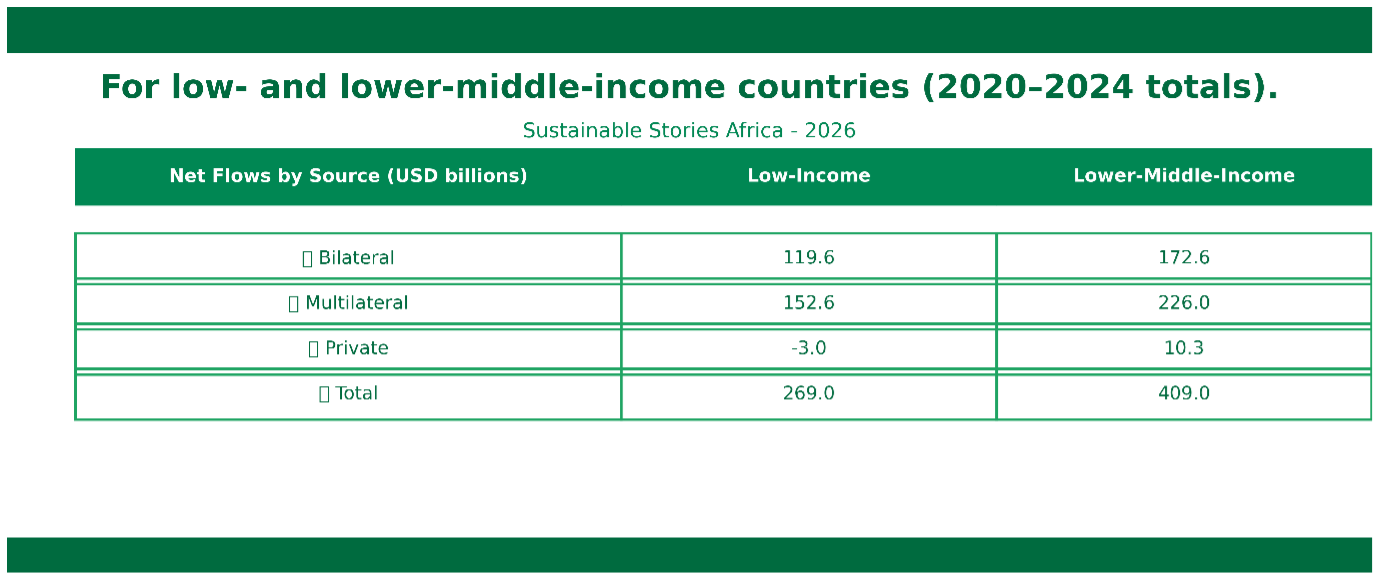

For low- and lower-middle-income countries (2020–2024 totals):

Net Flows by Source (USD billions) | Low-Income | Lower-Middle-Income |

|---|---|---|

Bilateral | 119.6 | 172.6 |

Multilateral | 152.6 | 226.0 |

Private | -3.0 | 10.3 |

Total | 269.0 | 409.0 |

Multilateral institutions provide grants, concessional lending, and technical expertise.

According to a 2024 survey referenced in the report, multilaterals ranked among the most influential and helpful providers for developing country leaders.

In a more fragmented geopolitical environment, multilaterals are emerging not just as lenders, but as system stabilisers.

Why Net Flows Data Matters Now

The report argues that analysing net flows, integrating inflows and debt service outflows, is essential for understanding real fiscal space.

Much public debate focuses on single categories, including Official Development Assistance (ODA), foreign direct investment (FDI), remittances or sovereign debt.

However, policymakers operate within the net reality of what remains after repayments.

The data landscape remains fragmented:

- Aid activity systems (OECD DAC, IATI, TOSSD) capture project-level detail.

- World Bank debt statistics capture aggregate debt flows.

- Adjacent flows like remittances and illicit financial flows sit outside government budgets.

There is no reconciled, timely, country-level view of total external finance. The Development Finance Observatory aims to build that integrated architecture, linking ODA, sovereign debt, private flows, and domestic budgets into a unified knowledge graph.

As aid cuts intensify in 2025 and debt service obligations remain high, this transparency becomes critical.

PATH FORWARD – Rebuilding Clarity, Strengthening Institutions

The global development finance architecture is entering a more frugal era. Multilaterals must continue to expand their concessional capacity, while bilateral donors reassess commitments, considering fiscal pressures.

Debt sustainability frameworks must better anticipate repayment spikes that erode fiscal space.

Equally important is data reform. Integrated, country-level net flow tracking, such as the Development Finance Observatory initiative, can empower finance ministries, journalists, and investors to “follow the money” in real time. In a world of shifting capital, clarity becomes a sense of power.