Africa produces more than 300 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas and accounts for 8.5% of global LNG supply; however, millions remain poor due to a lack of consistent energy availability.

The State of African Energy 2026 report makes one thing clear: gas and LNG will shape the continent’s industrial future, but only if monetisation strategies align with domestic power, infrastructure and climate goals.

For Nigeria, the question is no longer whether gas matters, but whether it can anchor a just transition.

Gas, LNG and the Just Transition Imperative

Africa’s gas story is accelerating. Production has surpassed 300 bcm, with LNG exports positioning the continent as a strategic supplier to Europe and Asia.

However, domestic utilisation lags, infrastructure gaps persist, and energy access remains uneven.

Pages 55–70 of The State of African Energy 2026 Outlook Report present a critical inflexion point: gas production is rising, but “finding demand” and balancing export ambitions with domestic obligations will define whether Africa’s gas boom becomes an industrial revolution, or another extraction cycle.

For Nigeria, with 113 Tcf of recoverable gas in the Niger Delta basin, this moment intersects directly with its Energy Transition Plan and Decade of Gas agenda. The opportunity is vast. So are the risks.

Africa’s Gas Surge Meets Demand Reality

Africa today accounts for 8.5% of global LNG supply (34.7 MMt in 2024) while producing over 300 bcm of natural gas annually. In terms of discovered underdeveloped gas resources, the continent ranks second globally.

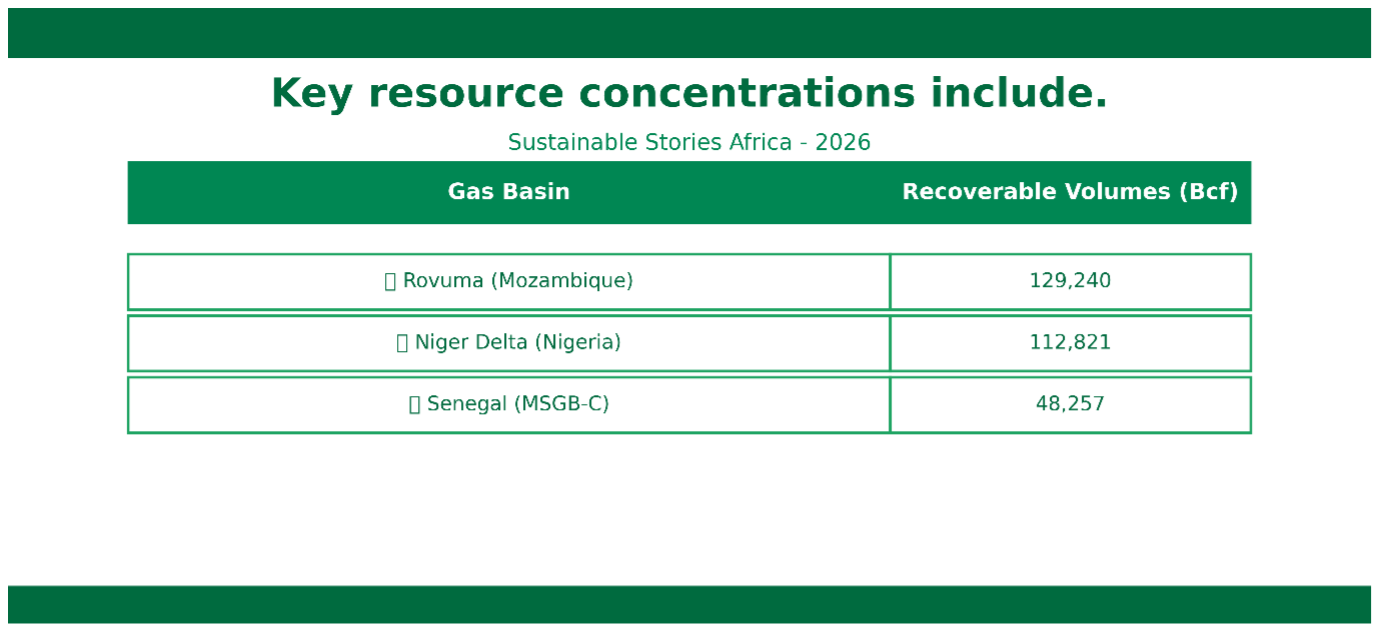

Key resource concentrations include:

Gas Basin | Recoverable Volumes (Bcf) |

|---|---|

Rovuma (Mozambique) | 129,240 |

Niger Delta (Nigeria) | 112,821 |

Senegal (MSGB-C) | 48,257 |

However, the report highlights a paradox: production growth does not automatically translate into domestic development.

LNG provides a route to monetisation, but domestic market obligations, infrastructure constraints and counterparty risk complicate execution.

Africa’s gas boom is not demand-constrained globally, but domestically misaligned.

Monetisation, Infrastructure and the Nigerian Question

The report highlights that gas-to-power remains the primary domestic demand across Africa.

However, domestic markets remain limited, with the power sector often acting as the dominant off-taker, leaving the petrochemicals, fertiliser, ammonia and transport sectors underdeveloped.

Nigeria illustrates this tension clearly.

- Gas flaring remains significant across Algeria, Nigeria and Libya, with Nigeria flaring 6.5 Bcm in 2024.

- LNG export infrastructure exists and continues expanding.

- Domestic transmission infrastructure remains uneven.

- Counterparty risks in power markets constrain upstream investment appetite.

The report’s case studies from Angola, Senegal and Mauritania emphasise similar bottlenecks: the lack of regional gas transport networks, an underdeveloped domestic industry, and tension between export pricing and domestic affordability.

For Nigeria, the challenge is sequencing:

- Export LNG to secure foreign exchange

- Simultaneously scale gas-to-power

- Expand industrial gas use (fertiliser, methanol, CNG, ssLNG)

- Reduce flaring and methane intensity

This balancing act sits at the heart of a just transition.

Gas as a Bridge to Industrial Sovereignty

The report projects that natural gas will account for 45% of Africa’s total power generation by 2050. In a continent where per capita electricity consumption was just 500 kWh in 2024, compared to 3,700 kWh globally, gas offers baseload reliability essential for industrial take-off.

Gas enables:

- Grid stability alongside renewables

- Fertiliser and ammonia production

- Mining decarbonisation in resource-rich economies

- CNG transition in transport (notably Nigeria)

- LNG-powered maritime trade

Africa contributes only 5% of global energy-related emissions, despite hosting 19% of the world’s population. This low baseline provides policy space to leverage gas as a transitional fuel while scaling renewables.

For Nigeria, gas underpins:

- The Energy Transition Plan’s emissions pathway

- Flare commercialisation programmes

- Domestic LPG expansion

- The Decade of Gas industrialisation strategy

However, the report is explicit: without infrastructure, including pipelines, processing hubs, and regional transport corridors, gas remains a stranded potential.

Aligning LNG Exports with Domestic Equity

The global context is tightening.

New emissions regulations, including the EU Methane Regulation and IMO frameworks, are increasing scrutiny on gas intensity and transparency. LNG competitiveness will increasingly depend on upstream decarbonisation and methane management.

Nigeria’s upstream sector faces elevated levels of emissions intensity, with flaring accounting for nearly half of total upstream emissions. Monetising associated gas presents both climate and economic dividends.

To align LNG growth with a just transition, policy priorities must include:

- Strengthening domestic gas pricing frameworks

- Accelerating pipeline infrastructure (AKK, OB3 expansions)

- Deepening regional power pool integration

- Scaling CNG and LPG penetration

- Embedding methane monitoring compliance into upstream operations

- Creating fiscal stability under the Petroleum Industry Act

Gas cannot be an export-only narrative. It must power factories, fertiliser plants, data centres, transport systems and homes.

Otherwise, Africa risks repeating the oil-era paradox: exporting value while importing development.

PATH FORWARD – Gas As Catalyst, Not Commodity

Africa’s gas opportunity is historic, but fragile. LNG expansion must be matched by domestic infrastructure investment, methane transparency and industrial policy coherence.

Nigeria’s Energy Transition Plan should embed gas as a transitional enabler, not a permanent dependency.

The path forward demands synchronised export growth and domestic equity, monetising resources while electrifying citizens.

Gas must power industrial transformation, reduce flaring, stabilise grids and unlock inclusive prosperity.