As we await Africa's Development Dynamics report for 2026, which highlights the 2025 activities of Africa, 2024 was locked in a new kind of energy risk: record-breaking heat drove electric demand far beyond historical norms just as climate swings reshaped wind, solar and hydropower output worldwide.

For the Global South, especially Africa, the year exposed how quickly "energy transition" ambitions can collide with climate reality.

Across regions, seasonal forecasts quietly proved their worth, correctly flagging dangerous spikes in cooling demand and swings in renewable output months in advance.

The bigger story is clear: climate intelligence is no longer a 'nice-to-have', it is fast becoming the backbone of resilient, equitable power systems.

Heat, anomalies and a grid on edge

The year 2024 was the warmest ever recorded, with global near‑surface temperatures averaging 1.55 °C above the pre‑industrial baseline, and that heat translated directly into electricity demand.

Temperature‑based energy‑demand rose 4% above the 1991–2020 mean and exceeded 20% in heat‑sensitive regions such as Western and Central Africa, South‑East Asia and parts of South America, signalling a structural shift in cooling needs. This is according to the 2025 Africa's Development Dynamics – Infrastructure, Growth and Transformation report released by the African Union (AU) and the OECD Development Centre (OECD).

At the same time, climate variability reshaped renewable energy performance, not just capacity additions. Wind and solar capacity factors were modestly positive at the global level in 2024; however, the averages contrast with sharp regional divergences, while hydropower swung from a global deficit in 2023 to a positive anomaly in 2024, underscoring how rainfall and river flows can make or break power systems in a warming world.

For system planners, the combination was combustible: more people relying on electricity during longer, hotter seasons, and a generation mix increasingly exposed to the same climate forces driving demand.

In that context, the report by the World Meteorological Organisation and the International Renewable Energy Agency reads less like an annual statistical digest and more like an emerging playbook for climate‑informed grids.

Where climate hits hardest

The report's four core indicators, wind and solar capacity factors, precipitation‑based hydropower and energy‑degree‑days demand show how unevenly climate risk landed in 2024.

Southern Africa, for instance, recorded some of the strongest anomalies worldwide: wind capacity factors rose between 8% and 16%, and solar between 2% and –6% on average; however, hydropower output remained below normal for a third straight year while demand reached record levels in most countries outside South Africa.

Across Western and Central Africa, annual energy‑demand anomalies exceeded 20%. This was driven by extreme heat and limited access to affordable cooling, in systems where solar and hydro capacity remain scarce relative to need.

In South Asia, India recorded a 16% surge in electricity demand in October, just as both wind and solar outputs underperformed, underscoring how overlapping climate stresses can squeeze supply margins even in a large, fast-growing power market.

Hydropower‑reliant regions saw some of the largest swings. In Central America and Mexico, a combined hydropower fleet of more than 20 GW, year‑on‑year variability reached 20%, which was equivalent to the annual consumption of roughly 3.5 million households, highlighting the exposure of dams to El Niño‑linked drought.

Eastern Africa, by contrast, benefited from above‑average rainfall and corresponding hydropower gains, likely shaped by a weakening El Niño and a moderately positive Indian Ocean Dipole.

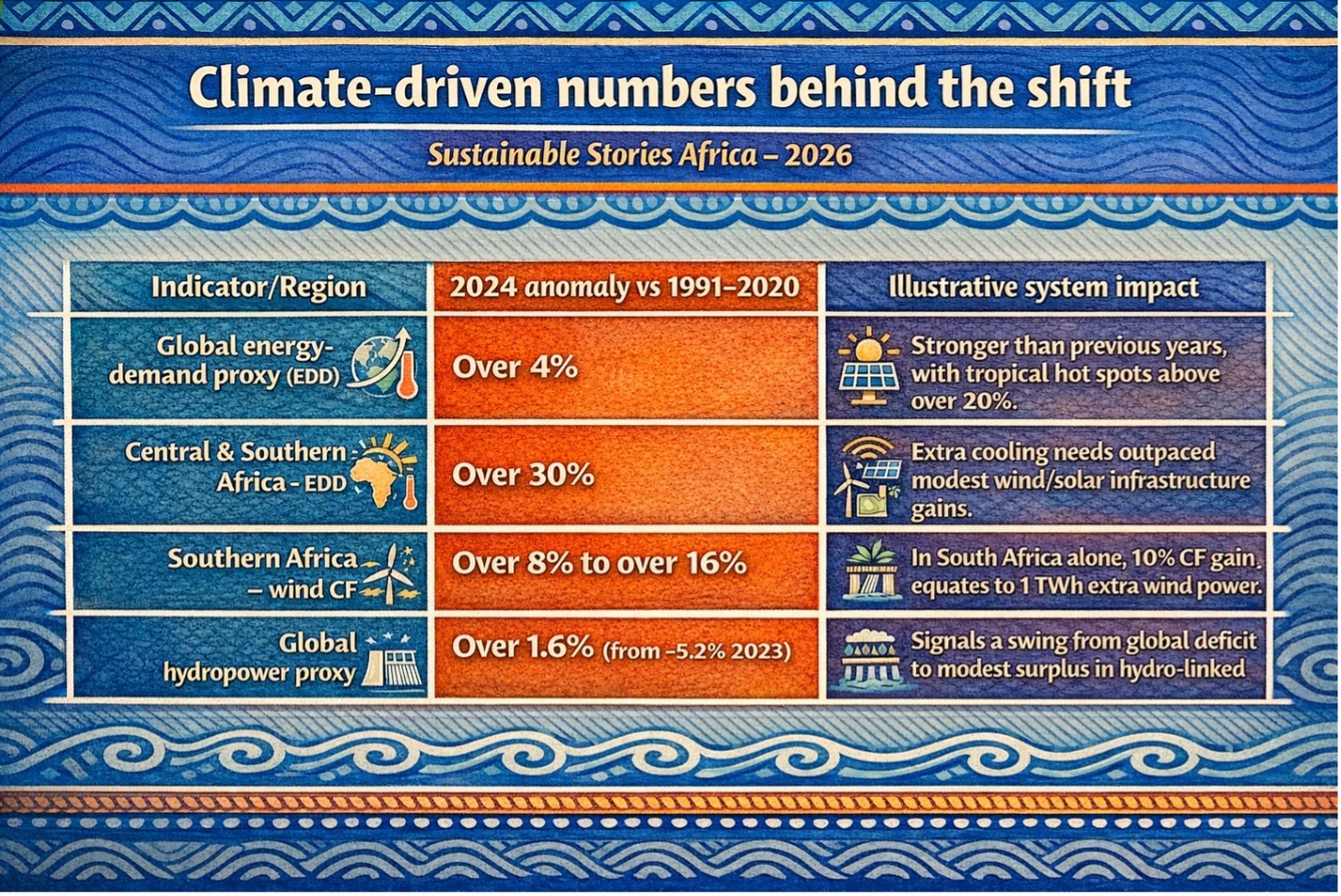

Climate‑driven numbers behind the shift

| Indicator / Region | 2024 anomaly vs 1991–2020 | Illustrative system impact |

|---|---|---|

| Global energy‑demand proxy (EDD) | Over 4% | Stronger than previous years, with tropical hot spots above over 20%. |

| Central & Southern Africa – EDD | Over 30% | Extra cooling needs outpaced modest wind/solar infrastructure gains. |

| Southern Africa – wind CF | Over 8% to over 16% | In South Africa alone, 10% CF gain equates to 1 TWh extra wind power. |

| Global hydropower proxy | Over 1.6% (from -5.2% 2023) | Signals a swing from global deficit to modest surplus in hydro‑linked precipitation. |

Turning variability into resilience

Against this backdrop, the economic case for resilient renewables is strengthening rather than weakening. By 2024, global installed renewable power had reached 4,448 GW, with solar photovoltaics and wind providing over two‑thirds of the record 584 GW capacity addition in a single year.

Costs have continued to reduce onshore wind projects delivered electricity at around $0.034 US per kWh and utility‑scale solar around $0.043 per kWh in 2024, making them 53% and 41% cheaper, respectively, than the lowest‑cost fossil alternatives. For African and other emerging markets, that cost gap represents a rare alignment of climate, development and fiscal priorities, provided systems are designed to handle variability.

The report outlines how seasonal climate forecasts are starting to close that gap between risk and opportunity. A July 2024 forecast, issued in June 2024, anticipated unusually high energy demand and lower than average solar performance across Africa, demonstrating that three‑to‑six‑month lead times can inform reservoir operations, maintenance schedules and cross‑border trading decisions before stress shows up on the grid.

Data, forecasts and regional services now

The authors identify four operational priorities that move climate intelligence from research into routine power‑sector practice.

- Close critical data gaps fast – Many countries still lack consistent measurements of hub‑height wind speeds, solar irradiance and even basic installed capacity and generation statistics, weakening models and investment decisions.

- Build regional climate‑energy services – Climate‑informed energy atlases and early‑warning systems are urgently needed in underserved regions such as Africa, which holds vast wind, solar and hydro potential but only about 1.5% of global renewable capacity.

- Integrate seasonal forecasts into operations – Utilities and system operators can start using seasonal outlooks to refine maintenance windows, flexible generation planning and demand‑response programmes, especially as heat‑driven cooling loads grow.

- Embed climate risk into NDCs and investment – Countries preparing the next round of Nationally Determined Contributions are encouraged to make energy targets explicitly climate‑risk‑informed, aligning grid expansion and generation plans with COP28 goals to triple renewables and double efficiency by 2030.

For African power pools and other regional markets, these steps translate into concrete pathways. Enhanced platforms sharing data, cross-border planning informed by shared climate diagnostics, and early warning protocols for droughts, heatwaves or ENSO transitions can reduce volatility in both supply and demand while improving investor confidence.

Path forward – Mapping priorities, keeping 1.5 °C alive - Resilient transitions need climate‑ready grids

The report's core warning is clear: tripling renewables will mean little if grids remain built for a climate that no longer exists.

Embedding wind, solar, hydro and demand signals into routine planning, backed by improved observations and seasonal forecasts, can curb curtailment, prevent blackouts and stretch scarce public financing.

For Africa, where capacity stands at 1.5% of the global total despite its world-class resources, climate-informed investment this decade will determine whether systems gain resilience or lock in new vulnerabilities.