Extreme heat is turning into a daily economic shock across Africa and Asia, cutting work hours, raising cooling costs, and worsening health risks for informal workers.

A new compilation of community lessons shows resilience is already being built through local early warnings, heat action plans, nature-based solutions, and worker-led innovations that protect livelihoods while climate hazards intensify.

Heat resilience begins where people live

Extreme heat is no longer a "weather story." It is a productivity story, a public health story, and a household budget story.

Across cities and rural communities, rising temperatures are pushing up the cost of water and cooling, shortening business hours, and making outdoor work increasingly unsafe.

This matters most for informal workers: a global workforce of roughly 2 billion people that is often excluded from official data systems and national climate planning, leaving livelihoods exposed and protections thin.

A special issue drawing lessons from communities in Africa and Asia shows what resilience looks like up close: heat action planning that reaches markets and streets, early warnings that trigger real decisions, and local solutions, from shade and water points to electric mobility and climate-smart farming, that can scale if funded and formalised.

Heat is now an economic hazard

Across Africa and Asia, extreme heat is emerging as a frontline climate risk, one that harms health, disrupts services, and erodes incomes.

Small businesses and informal workers often face the sharpest exposure because their work is outdoors, their margins are thin, and their ability to absorb higher costs is limited.

In urban India, small businesses in Ahmedabad and Guwahati report consistent heat impacts: lower productivity, fatigue, higher household expenses, disrupted food practices, and more uncertain access to drinking water.

Electricity bills commonly rise 25–50% in summer months, forcing coping strategies like reduced operating hours, especially in open markets with little shade.

What the field lessons reveal

The report's core insight is simple: resilience is strongest when communities aren't treated as beneficiaries, but as partners in planning, data, and delivery.

Across the featured cases:

- Urban governance is evolving – India's NDMA Heat Action Guidelines (2024) and early warning upgrades are enabling cities to move from reactive responses to anticipatory heat governance.

- Local networks save time and lives – In Nepal, linking ward offices, municipalities, community volunteers, schools, health posts, and local media improved flood readiness through practical coordination and micro-grants.

- Livelihood resilience is climate resilience – Ghana's community-based producer groups and local leadership models show adaptation works better when it strengthens incomes and restores ecosystems together.

Heat impacts on informal livelihoods (selected evidence)

| Evidence points | What it signals | Where it appears |

|---|---|---|

| Informal workers: 2 billion globally | Scale of exposure outside formal safety nets | Introduction framing |

| Summer electricity bills up 25 % – 50% | Heat → immediate household/business cost shock | Urban India small-business findings |

| Women face a disproportionate burden | Heat risk intersects with care + paid work | Urban India findings |

| Early warning systems aim for coverage by 2027 | Global shift toward people-centred preparedness | EW4All overview |

Why systems fail and what works

The report shows that heat resilience fails when it is treated as an "infrastructure-only" problem. Heat is also a labour, service-access, and information problem—made worse by weak data systems and exclusion of informal workers from planning.

What works, repeatedly, is a whole-of-society approach—where warnings translate into actions, and where municipal codes, finance, and worker protections keep pace with climate reality.

A notable systems example is Early Warnings for All (EW4All): a UN initiative launched in 2022 aiming to ensure everyone is protected by early warning systems by 2027, built on four pillars (risk understanding, hazard monitoring, warning dissemination, preparedness). Tajikistan's rollout shows why political leadership plus local capacity-building matters—especially Pillar 4: preparedness to respond.

The numbers behind practical adaptation

Community adaptation is not just narrative—it's measurable economics.

In Kenya, transport workers organising around electric mobility quantify both emissions and savings. In Ghana, climate-smart agriculture efforts show how resilience can stabilise food systems and incomes. In India, small business heat coping strategies underline why micro-insurance and cooling finance matter.

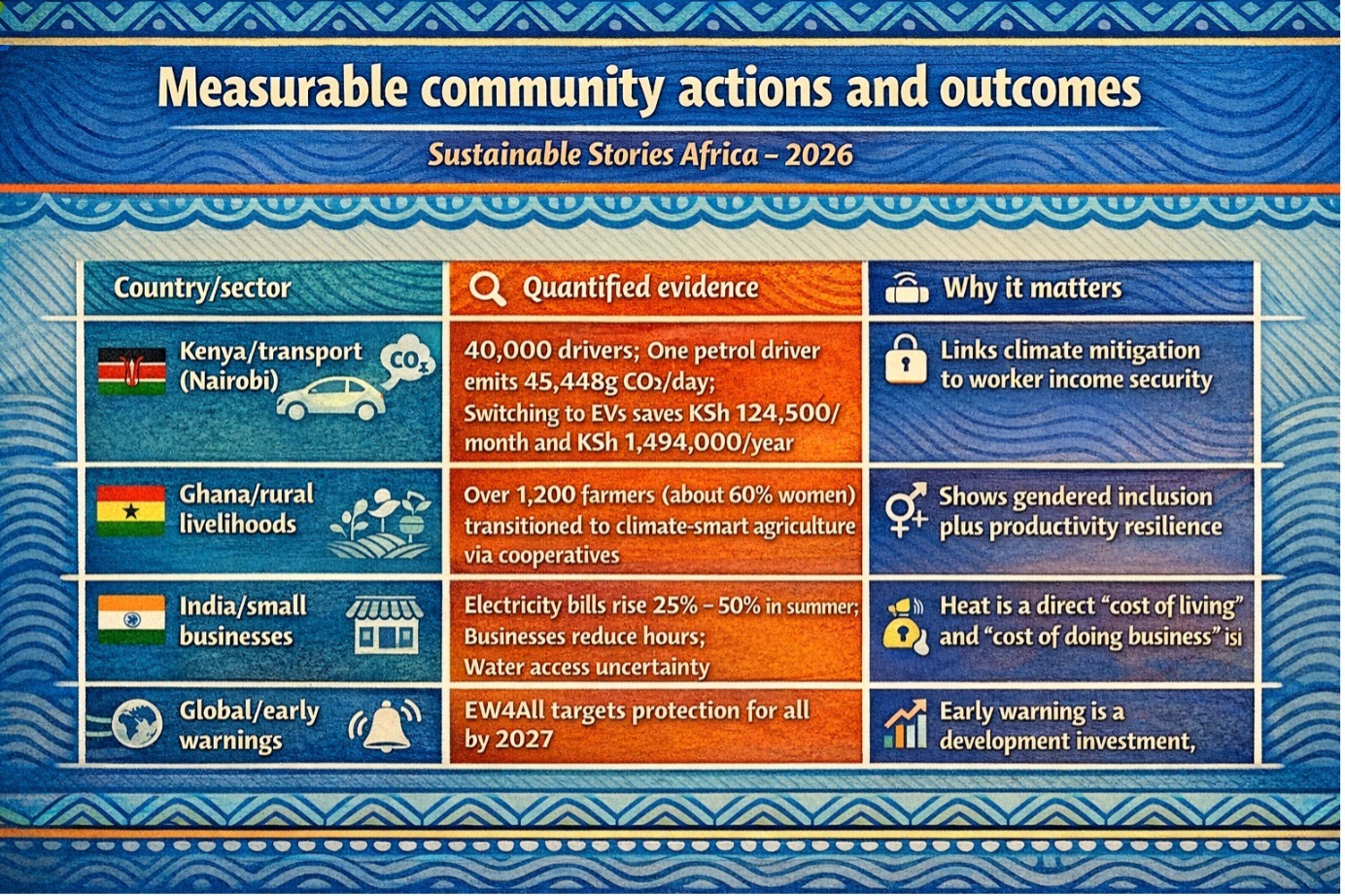

Measurable community actions and outcomes

| Country/sector | Quantified evidence | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Kenya/transport (Nairobi) | 40,000 drivers; one petrol driver emits 45,448g CO₂/day; switching to EVs saves KSh 124,500/month and KSh 1,494,000/year | Links climate mitigation to worker income security |

| Ghana/rural livelihoods | Over 1,200 farmers (about 60% women) transitioned to climate-smart agriculture via cooperatives | Shows gendered inclusion plus productivity resilience |

| India/small businesses | Electricity bills rise 25 % – 50% in summer; businesses reduce hours; water access uncertainty | Heat is a direct "cost of living" and "cost of doing business" issue |

| Global/early warnings | EW4All targets protection for all by 2027 | Early warning is a development investment, not an add-on |

PATH FORWARD – Put resources where risks concentrate

Extreme heat resilience is already being built, from market stalls to farmlands, but scaling depends on finance, data, and governance catching up to lived reality.

Priorities are clear: formalise heat-safe work standards, fund local early warning-to-action systems, expand micro-insurance and cooling finance for small businesses, and place informal workers inside climate planning, not outside the data.