Ghana's decision to abolish its 15% VAT on mining exploration marks one of its most consequential policy shifts in decades, reshaping competition across West Africa's gold corridor.

Abolished Tax Tilts Ghana's Mining Future

Ghana has scrapped its 15% value-added tax on mining exploration, ending a 25-year policy that industry leaders say quietly crippled the country's competitiveness.

The reversal comes at a time when global mining capital is shifting rapidly across West Africa, and Ghana, long considered a stable mining hub, found itself losing ground to neighbours offering tax-free exploration zones.

For years, early-stage explorers paid VAT on drilling, laboratory tests, and geological assessments, the most expensive phase of resource development, while competitors in Cote d'Ivoire and Burkina Faso enjoyed full exemptions. "It was a clog on the pipeline of projects," said Ghana Chamber of Mines president Michael Akafia. "Explorers simply went elsewhere."

Data Reveals the Cost of Lost Competitiveness

The policy was especially punishing given exploration's high-risk economics: companies spend millions before discovering a viable deposit. Between 2000 and 2024, exploration migration to neighbouring countries surged as Ghana charged 15% on nearly all exploration costs.

Meanwhile, artisanal and small-scale miners (ASM) quietly rewrote Ghana's mining story. Between January and October 2025, ASM exported 81.7 metric tons of gold worth $8.1 billion, surpassing large-scale producers' 74.1 tons worth $6.6 billion for the first time in history.

Ghana's 2025 Gold Output (Jan–Oct)

| Segment | Output (metric tons) | Value (USD) |

|---|---|---|

| Small-Scale / ASM | 81.7 | $8.1B |

| Large-Scale Mines | 74.1 | $6.6B |

This unprecedented shift has emboldened government ambitions to reposition Ghana as a long-term exploration destination, not just a mature mining economy.

Why Ending the VAT Resets the Regional Chessboard

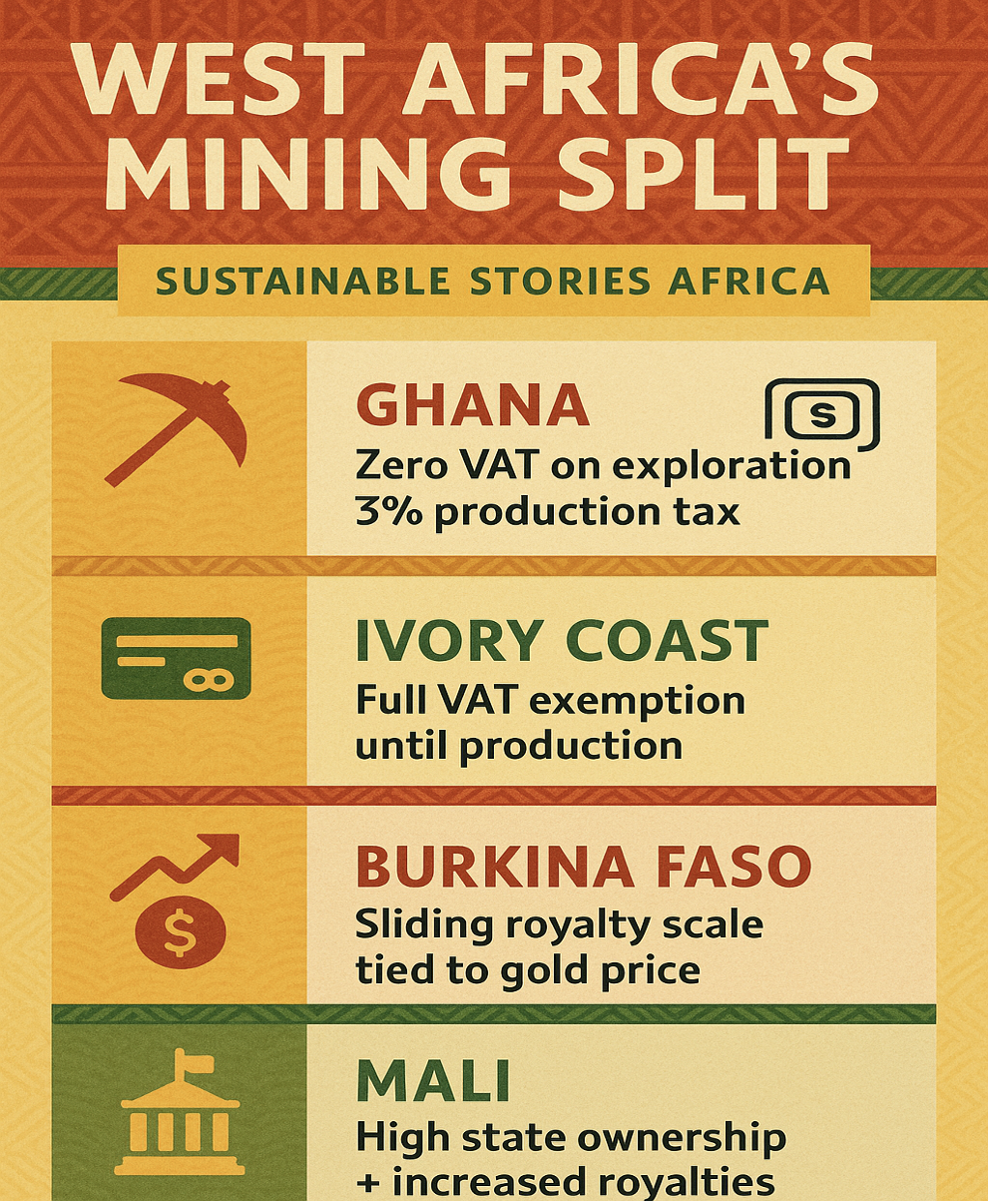

Across West Africa, a fierce mining strategy divide is emerging. Mali and Burkina Faso are tightening fiscal screws: raising royalty rates, increasing state ownership, and even seizing gold shipments. The result? Mali's gold output fell 23% in 2024, but government revenue shot up 52.5%.

Ghana, by contrast, is betting on openness, not extraction pressure, as its long-term competitive edge. It has tripled production tax from 1% to 3% to boost revenues but cut exploration VAT to zero. The message to investors is clear: "Spend more on finding gold here; we'll tax production fairly later."

West Africa's Mining Split

Investors Reconsider Ghana, but Questions Remain

Major operators, such as Newmont, AngloGold Ashanti, Perseus, Gold Fields, now face a more predictable exploration landscape. The government has simultaneously launched audits to boost earnings from existing operations, hoping that increased revenue offsets short-term VAT losses.

But the stakes are higher than tax policy. The broader question is whether Ghana can attract responsible capital without repeating old extractive patterns where foreign profits soared while local communities remained poor. Industry watchers say the next 12–24 months will determine whether Ghana leads or lags in the continent's mining future.

Path Forward – Lower Barriers, Higher Returns, Fairer Outcomes

Ghana's exploration tax reset marks a strategic rebalancing: lower upfront costs for explorers, stronger fiscal tools for the state, and renewed investor interest.

Achieving durable impact requires tight environmental governance, community-centred benefits, and transparent production-stage taxation.

If implemented effectively, Ghana could emerge as West Africa's stable, long-horizon mining destination, offering clarity, competitiveness, and shared prosperity.