The world is no longer in a water crisis. It is in a state of water bankruptcy.

A new UN flagship report warns that many water systems cannot return to historical baselines, marking a structural shift in global hydrological stability.

With four billion people facing severe water scarcity annually and droughts costing $307 billion each year, researchers say the era of temporary "crises" is over.

Global Water Bankruptcy Redefines Scarcity Risk

The world has crossed a dangerous threshold in water security, according to a flagship report released by UN researchers, who warn that many regions are no longer experiencing a temporary "water crisis" but a condition of structural "water bankruptcy."

"For much of the world, 'normal' is gone," said Kaveh Madani, Director of the UN University Institute for Water, Environment and Health. "This is not to kill hope but to encourage action and an honest admission of failure today to protect and enable tomorrow."

The shift in language signals a deeper warning: water systems in several regions may not realistically recover to historical levels due to over-extraction, pollution and irreversible ecosystem loss.

From Crisis to Bankruptcy

The report reframes global water stress as insolvency plus irreversibility.

- Insolvency: Withdrawing and polluting water beyond renewable inflows and safe depletion limits.

- Irreversibility: Permanent damage to wetlands, lakes and aquifers that prevents restoration.

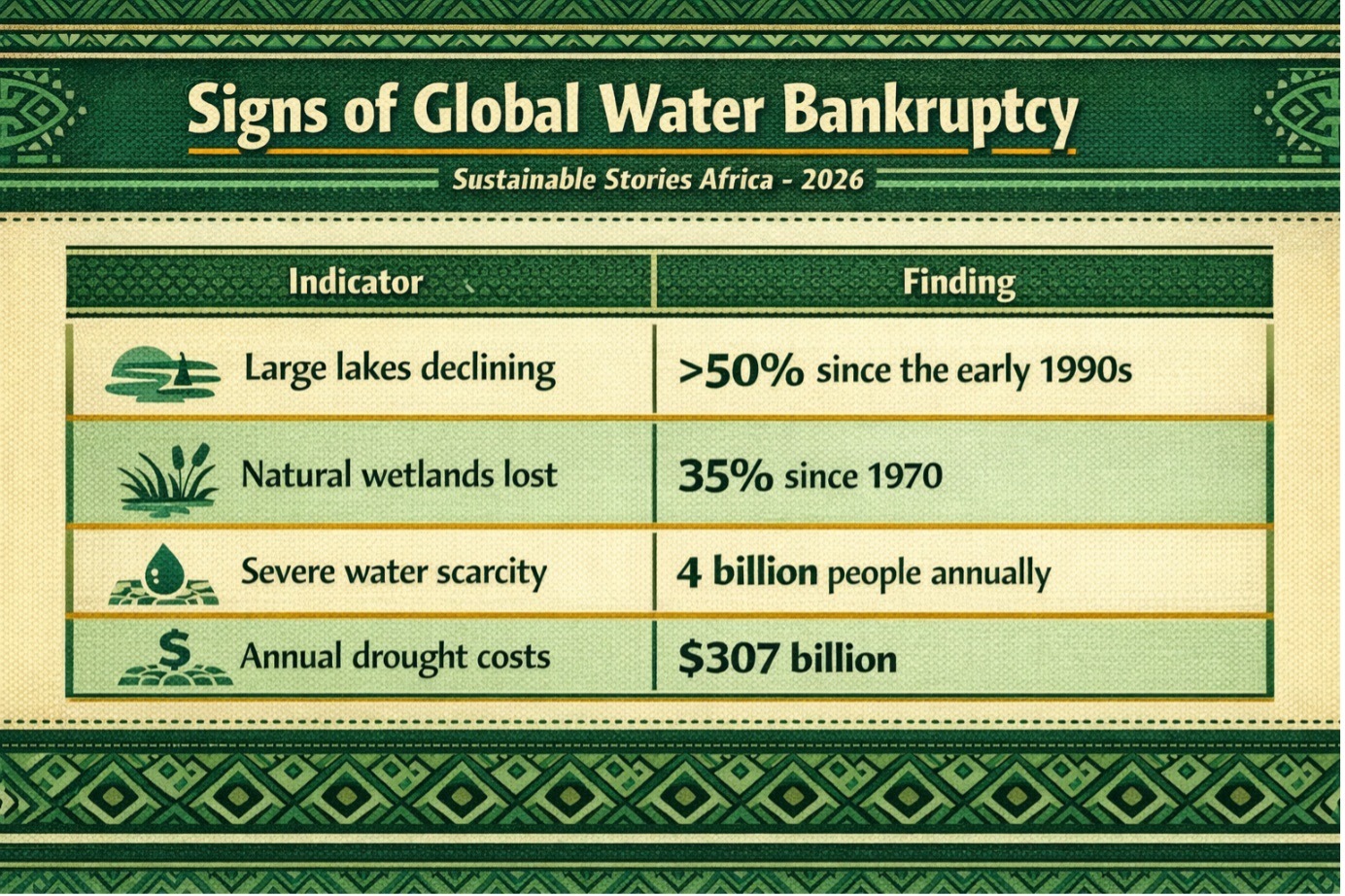

More than half of the world's large lakes have declined since the early 1990s. Around 35% of natural wetlands have been lost since 1970.

Signs of Global Water Bankruptcy

| Indicator | Finding |

|---|---|

| Large lakes declining | >50% since the early 1990s |

| Natural wetlands lost | 35% since 1970 |

| Severe water scarcity | 4 billion people annually |

| Annual drought costs | $307 billion |

Nearly 75% of the global population now lives in water-insecure or critically water-insecure countries.

Unequal Burdens, Global Interdependence

Mr Madani emphasised that not all systems are bankrupt, but enough are interconnected through trade, migration and geopolitics to shift global risk.

The burdens fall disproportionately on smallholder farmers, Indigenous Peoples, low-income urban residents, women and youth. Meanwhile, the gains from overuse often accrued to more powerful actors.

Water bankruptcy, the report argues, is not an isolated mismanagement; it is a systemic imbalance with economic and social spillovers.

A Structured Recovery Blueprint

Despite the severity, researchers insist that bankruptcy is not the end; it is the beginning of the restructuring required.

"It is the start of a structured recovery plan: you stop the bleeding, protect essential services, restructure unsustainable claims, and invest in rebuilding," Mr Madani said.

The framework calls for:

- Protecting remaining water-related natural capital.

- Aligning policies with hydrological realities.

- Ending short-term crisis management approaches.

The analogy is financial: acknowledge insolvency, stabilise essentials, then rebuild sustainably.

Shift From Crisis to Management

The report urges governments to transition from reactive emergency measures to structured bankruptcy management, grounded in transparency about irreversible losses.

"If we continue to manage these failures as temporary 'crises' with short-term fixes, we will only deepen ecological damage and fuel social conflict," Mr Madani warned.

Water governance must now match the scale of depletion, not the memory of abundance.

Path Forward – Stabilise Systems, Restructure Water Claims

Governments must admit hydrological insolvency where it exists, protect essential water services, and align allocation with renewable limits.

Subsidies and extraction practices that exceed natural replenishment must be restructured.

Bankruptcy is not surrender; it is discipline. Managing water as a finite natural capital, rather than an endlessly renewable resource, is now the central test of global resilience.

Culled From: https://news.un.org/en/story/2026/01/1166800