Nigeria’s rivers are carrying more than water. They are carrying fragments of its development model.

A nationwide review highlights that microplastics are present in lagoons, inland rivers, seafood, sachet water, table salt and treated municipal supplies, signalling a slow-moving environmental crisis with implications for food security, public health and economic resilience.

Nigeria’s Waters Under Plastic Siege

Across Nigeria’s lagoons, rivers and coastal creeks, scientists are detecting a contaminant invisible to the naked eye but increasingly impossible to ignore: microplastics.

Defined as plastic particles smaller than 5 mm, these fragments now permeate surface waters, sediments, fisheries, and even packaged drinking water consumed daily by millions.

The comprehensive 2026 review synthesising data for the periods between 2014 and 2026 concludes that microplastics are widespread across all geopolitical zones, with southern coastal systems recording the highest concentrations.

What began as a marine litter problem has evolved into a systemic challenge of aquatic contamination.

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, generates an estimated 2.5 – 3.0 million metric tonnes of plastic waste annually.

With formal recycling rates below 15%, the majority of this material follows a linear trajectory: production, use, disposal, and leakage into drains, rivers and wetlands.

Invisible Particles, Visible Consequences

Microplastics now dominate aquatic pollutant profiles globally, accounting for between 60% and 95% of estimated plastic debris in water bodies.

Globally, only between 9% and 10% of plastics are recycled. Nigeria reflects this global imbalance, but with heightened vulnerability due to rapid urbanisation and limited waste infrastructure.

The review identifies fibres and fragments, largely polyethene (PE), polypropylene (PP) and polyester, as the dominant polymers in Nigerian waters. These originate from degraded packaging, sachet water films, textiles, fishing gear and industrial inputs.

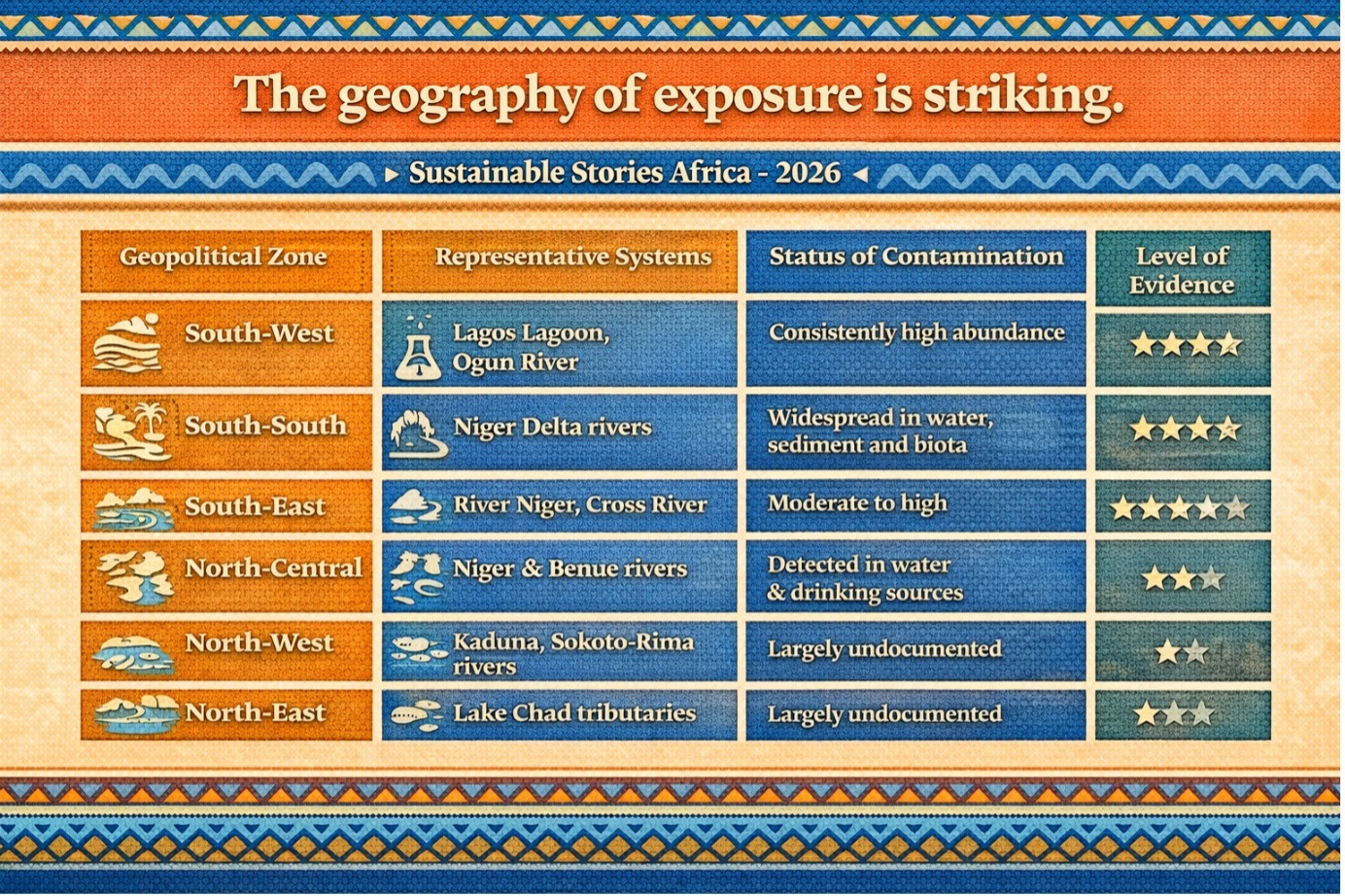

The geography of exposure is striking:

Geopolitical Zone | Representative Systems | Status of Contamination | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

South-West | Lagos Lagoon, Ogun River | Consistently high abundance | High |

South-South | Niger Delta rivers | Widespread in water, sediment, and biota | High – Moderate |

South-East | River Niger, Cross River | Moderate to high | Moderate |

North-Central | Niger & Benue rivers | Presence confirmed | Low – Moderate |

North-West | Kaduna, Sokoto-Rima | Detected in water & drinking sources | Low |

North-East | Lake Chad tributaries | Largely undocumented | Very Low |

The pattern suggests a south–north gradient, with inland systems functioning as both recipients and transport corridors.

From Rivers To Dinner Plates

The most alarming findings relate to biota and human exposure.

The studies report the presence of microplastics in the gastrointestinal tracts of fish of commercially important species.

Fibres dominate ingestion profiles, and histological changes, including inflammation and tissue damage, have been documented.

Drinking water is not exempt. Research detected microplastics in sachet water, bottled water, and treated municipal supplies.

A study in Kaduna identified particles in raw water (153 particles/L), treated water (25 – 36 particles/L), and even table salt.

In River Osun, concentrations reached 22,079 particles/L, which is among the highest recorded for river water globally.

Sediments function as long-term sinks, especially in mangroves and lagoons, while rainy seasons redistribute particles inland to the coast.

The economic implications extend beyond ecology. The pollution by plastic costs the global economy an estimated $13 billion annually in tourism losses, while damages for West Africa are estimated to be between $10,000 and $330,000 per metric tonne of plastic waste.

A Circular Economy Alternative Is Possible

Encouragingly, global policy experiments show that plastic leakage is reversible.

In Ireland, a €0.15 levy reduced the consumption and use of plastic bags by 90%. Wales achieved a 96% reduction after introducing a five-pence charge.

The European Union has mandated restrictions on single-use plastics by 2030.

Nigeria has initiated phased bans on select single-use plastics and strengthened its National Policy on Plastic Waste Management. However, implementation gaps persist.

UNEP estimates that a circular economy approach could reduce plastic waste by between 40% and 50% and avoid up to 9.1 million metric tonnes of CO₂ emissions.

The pathway is clear: source reduction, extended producer responsibility, wastewater filtration upgrades, data-driven monitoring and the integration of informal waste pickers into formal systems.

Treat Plastic As Infrastructure Policy

Microplastics are not merely an environmental nuisance. They are a governance signal.

They reveal structural deficits in urban planning, waste financing and potable water access. Sachet water dominance, which accounts for between 40% and 50% of visible urban plastic waste, is a fundamental failure in the water infrastructure system.

Three urgent steps emerge:

- National Harmonised Monitoring Framework – Standardise sampling, polymer identification (FTIR/Raman), and reporting protocols across all zones.

- Wastewater & Stormwater Controls – Install microfibre capture technologies and improve drainage management.

- Producer Accountability & Circular Incentives – Mandate extended producer responsibility and incentivise recyclable packaging redesign.

Nigeria’s fisheries, wetlands and coastal tourism industries depend on the integrity of the ecosystem. Without decisive intervention, microplastics may quietly erode economic and biological resilience.

The science is no longer emerging. It is converging.

Path Forward – Build Data, Enforce Policy

Nigeria must transition from fragmented studies to a coordinated national surveillance system spanning all river basins.

Harmonised monitoring, polymer fingerprinting, and public reporting will strengthen evidence-based regulation.

Policy must move from announcement to enforcement. Scaling circular-economy incentives, upgrading wastewater infrastructure, and aligning producer responsibility schemes will determine whether Nigeria bends its plastic trajectory or watches its rivers carry the cost downstream.