Africa's solar expansion is accelerating, driven by falling costs and climate urgency. However, as utility-scale solar spreads across rural landscapes, questions are emerging about its local environmental footprint.

From land use and biodiversity to water demand and community livelihoods, solar power brings both risks and opportunities. With the right planning, Africa can harness clean energy while protecting ecosystems, but without it, green ambition could carry unintended consequences.

Solar Growth Meets Local Realities

Africa's solar revolution is gathering pace. Falling technology costs, rising electricity demand and global climate commitments have made large-scale solar photovoltaic (PV) plants a central pillar of the continent's energy future.

Globally, solar PV already accounts for 42% of the installed renewable energy capacity and 77% of new renewable energy additions, with costs now 41% lower than fossil fuels.

However, as solar farms expand across Africa's landscapes, a more complex conversation is emerging, one that extends beyond megawatts and climate targets.

Large-scale solar plants reshape land use, affect wildlife habitats, alter microclimates and influence water availability. These local impacts, positive and negative, now sit at the heart of the energy transition debate.

IRENA's 2026 assessment makes one thing clear: solar power is not just an energy technology; it is a land-use decision, an environmental intervention and a community issue.

The challenge for Africa is not whether to build solar, but how to build it sustainably.

Solar Power, Environmental Trade-Offs

Solar PV is central to the global climate agenda. By 2050, it is expected to deliver 37% of renewable electricity and avoid 3.2 gigatonnes of CO₂ annually. However, large-scale solar plants interact with local ecosystems in ways that are often overlooked.

Construction typically involves land clearing, excavation and fencing activities that can disrupt vegetation, degrade soil and fragment wildlife habitats. In China's Gansu Province, native vegetation cover declined from an estimated 10–15% to less than 2% following the development of large-scale solar projects. Ecological recovery has been gradual, with partial regeneration observed only after at least three years.

Solar farms have also been built inside Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs), with over 200 projects globally located in sensitive ecosystems by 2020. These areas are essential for wildlife conservation and ecological services.

Africa's solar ambitions must therefore balance climate gains with ecological responsibility.

Land Use: Less Competition Than Feared

One of the most persistent concerns around solar PV is land competition with agriculture. Yet evidence suggests these fears are often overstated.

Globally, solar PV occupied just 3–7 million hectares in 2023—less than 0.1% of agricultural land. Even by 2050, it is expected to use only 0.2%–1.5% of global farmland.

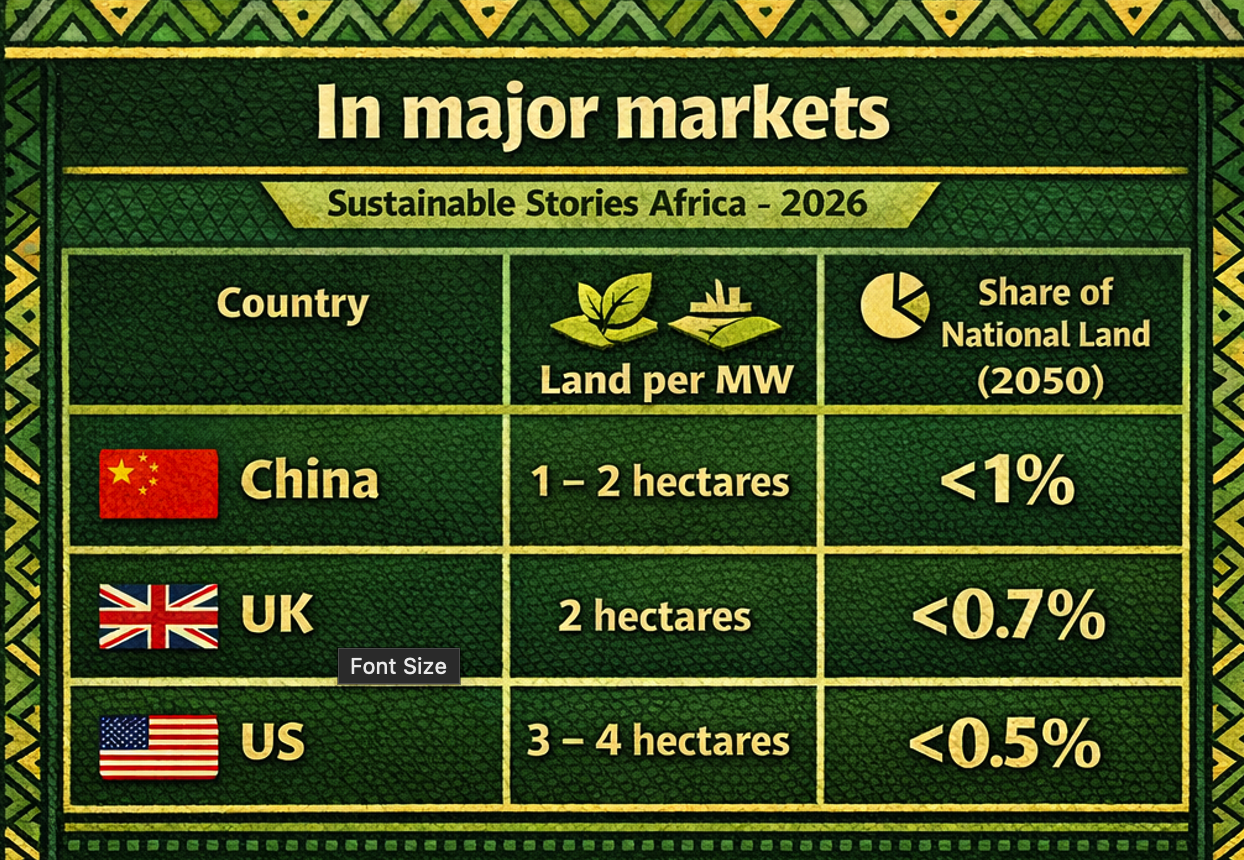

In major markets:

| Country | Land per MW | Share of National Land (2050) |

|---|---|---|

| China | 1 – 2 hectares | <1% |

| UK | 2 hectares | <0.7% |

| US | 3 – 4 hectares | <0.5% |

Ironically, land used for golf courses often exceeds that used for solar farms by several multiples in countries such as the United States, Japan and Australia.

For Africa, where land scarcity varies widely, integrated planning and community engagement remain essential, especially in small island states and densely populated regions.

When Construction Disrupts Nature

Solar PV construction can trigger a cascade of environmental impacts:

- Vegetation loss and slow recovery

- Soil erosion and compaction

- Flooding risks during rainy seasons

- Disturbance to wildlife breeding

- Habitat fragmentation

In sloping or desertified regions, excavation can damage biological soil crusts that prevent erosion and sandstorms. Without proper restoration, projects may accelerate land degradation instead of reversing it.

Forested areas are especially sensitive. Forests host over 80% of terrestrial biodiversity, yet solar projects built in wooded zones can contribute to deforestation and ecosystem disruption.

Wildlife at Risk

Solar infrastructure brings new hazards for wildlife:

- Bird collisions with panels and powerlines

- Electrocution from grid infrastructure

- Invasive species from replanting

- Fenced areas blocking animal movement

In California, solar plants were linked to 2.49 bird deaths per MW per year. Birds often mistake reflective panels for water, leading to fatal consequences.

Power lines associated with solar farms also increase fire risks and service disruptions, compounding both ecological and economic costs.

Solar Can Restore, Not Just Replace

Despite these risks, solar PV can also deliver powerful environmental co-benefits—when designed thoughtfully.

Cooling the Land

Solar panels reduce ground temperatures by 0.5–1°C during hot seasons, easing heat stress on soil and crops.

Saving Water

Evaporation under panels drops by 9–24%, improving water efficiency. In Tanzania, agrivoltaic projects cut irrigation demand by 13.8%.

Boosting Soil Health

Soil moisture increases by 15–39%, while organic matter and nutrients rise by over 80% in some Chinese projects.

4. Restoring Degraded Land

In Gonghe County, China, vegetation cover rose from <2% to over 55% within a decade of solar deployment on degraded land.

These gains demonstrate that solar farms can act as environmental restoration tools, not just energy assets.

Agriculture and Solar Can Coexist

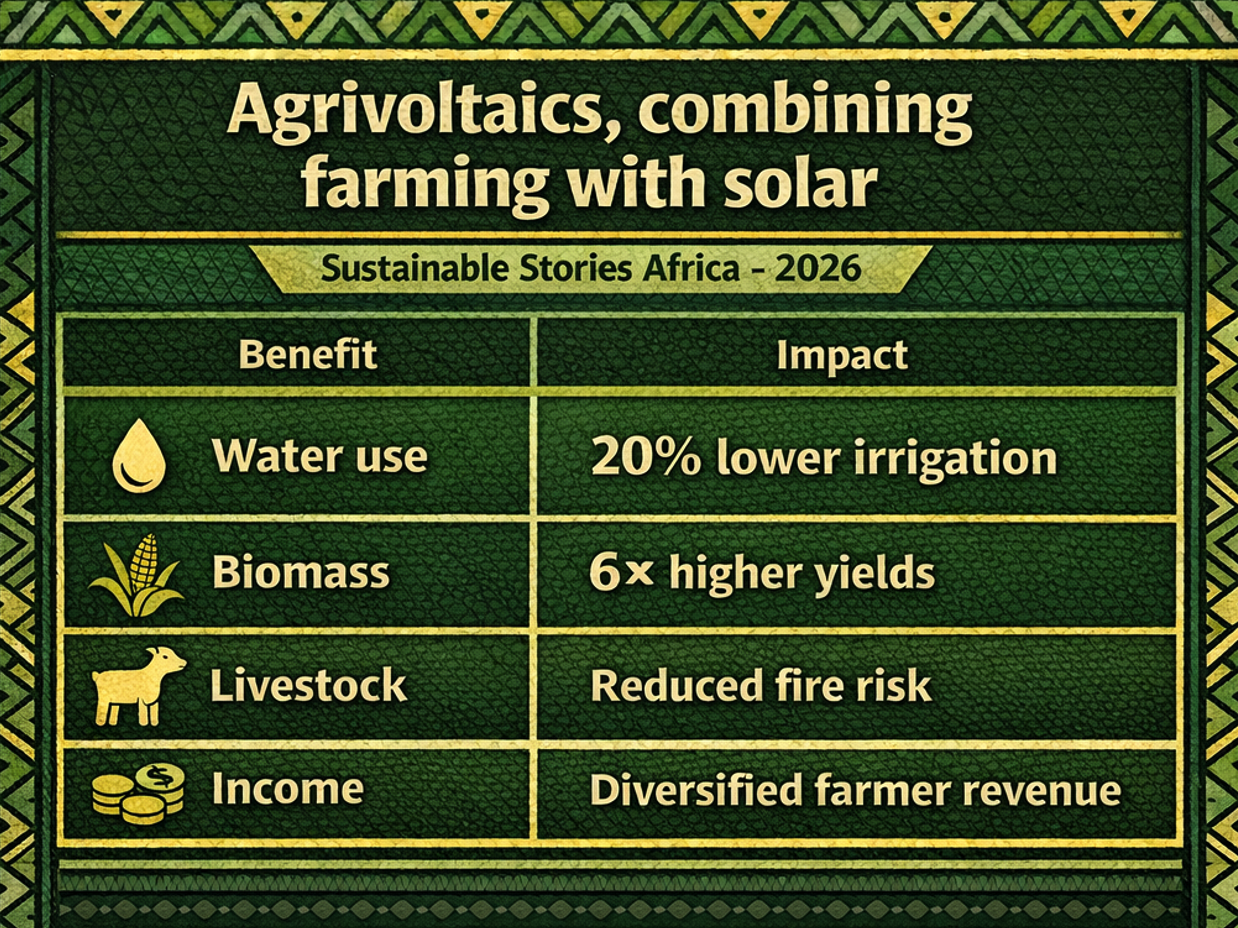

Agrivoltaics, combining farming with solar, offers a powerful solution:

| Benefit | Impact |

|---|---|

| Water use | 20% lower irrigation |

| Biomass | 6× higher yields |

| Livestock | Reduced fire risk |

| Income | Diversified farmer revenue |

Solar grazing and crop cultivation under panels can enhance food security while maintaining energy production. In dry African regions, this synergy could prove transformative.

Hidden Impacts in the Supply Chain

Environmental risks extend beyond project sites.

By 2030, solar PV manufacturing will require:

- 2.6 million tonnes of aluminium

- 0.18 million tonnes of copper

- 4,000 tonnes of silver

If sourced from virgin mining, these materials could cause habitat loss, water pollution and geohazards.

At the end of life, improperly handled panels release toxic substances such as hydrogen fluoride and heavy metals like lead and zinc into the soil and groundwater.

Countries such as Australia, China, the EU and the US now ban landfill disposal of solar panels and promote recycling—creating green jobs in the process.

Policy Must Lead the Transition

IRENA outlines a clear framework for sustainable solar deployment:

Key Policy Tools

- Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEA)

- Cumulative Impact Assessments (CIA)

- Biodiversity mapping

- Integrated land-use planning

- Financial incentives for co-benefits

Six Nature-Positive Principles

- Accelerate nature-positive siting

- Co-utilise land

- Conserve and restore ecosystems

- Monitor and adapt

- Extend plant lifecycles

- Engage local communities

However, barriers remain:

- Higher upfront costs

- Limited technical expertise

- Weak land-use policies

- Lack of industrial standards

Without reform, community opposition, legal delays and environmental damage could slow Africa's solar momentum.

PATH FORWARD – Power, Nature, Planning, People, Protection, Progress

Africa's solar future must integrate biodiversity protection, community engagement and circular economy principles into every project stage.

With stronger environmental assessments, inclusive land-use planning and incentives for co-benefits, solar PV can deliver clean energy while restoring ecosystems and strengthening local livelihoods.