Africa is adding workers faster than any region in history, about 12 million young people a year, for just 3 million new formal wage jobs. Without a radical shift in how the continent grows, that math points to mounting frustration rather than shared prosperity.

However, a different story is still possible. New analysis has identified five underutilised assets: a young workforce, a 1.3-billion-person market, entrepreneurial firms, digital rails, and vast agricultural potential, which could power millions of dignified jobs if governments transition from fragmented projects to corridor-led strategies that shape markets.

The rising generation, missing quality jobs

Africa’s youth bulge is colliding with a labour market unprepared for its scale. Over the coming decades, the continent’s working-age population is expected to expand by approximately 740 million, with 12 million young people entering the workforce annually against just 3 million new formal jobs.

Without productivity gains, demographic momentum risks deepening fragility rather than driving growth.

However, this surge could be Africa’s greatest asset. Brookings’ Africa Growth Initiative argues that existing strengths, including youthful talent, a continental market, vibrant entrepreneurship, digital expansion and agricultural capacity, can be aligned into corridor-based strategies that convert informality into scale and productivity

Youth boom, but jobs lag behind

Africa is projected to house a quarter of the world’s population by 2050, with its workforce expanding faster than any other region.

The World Bank estimates a net increase of 740 million working-age Africans by mid-century. However, job creation lags: 12 million enter the labour market annually, against just 3 million new formal roles.

This gap is structural. Without productivity gains, workers will remain trapped in low-margin informality, straining social contracts.

As Brookings’ Pierre Nguimkeu argues, Africa needs not only more jobs, but better, productive, stable and dignified work.

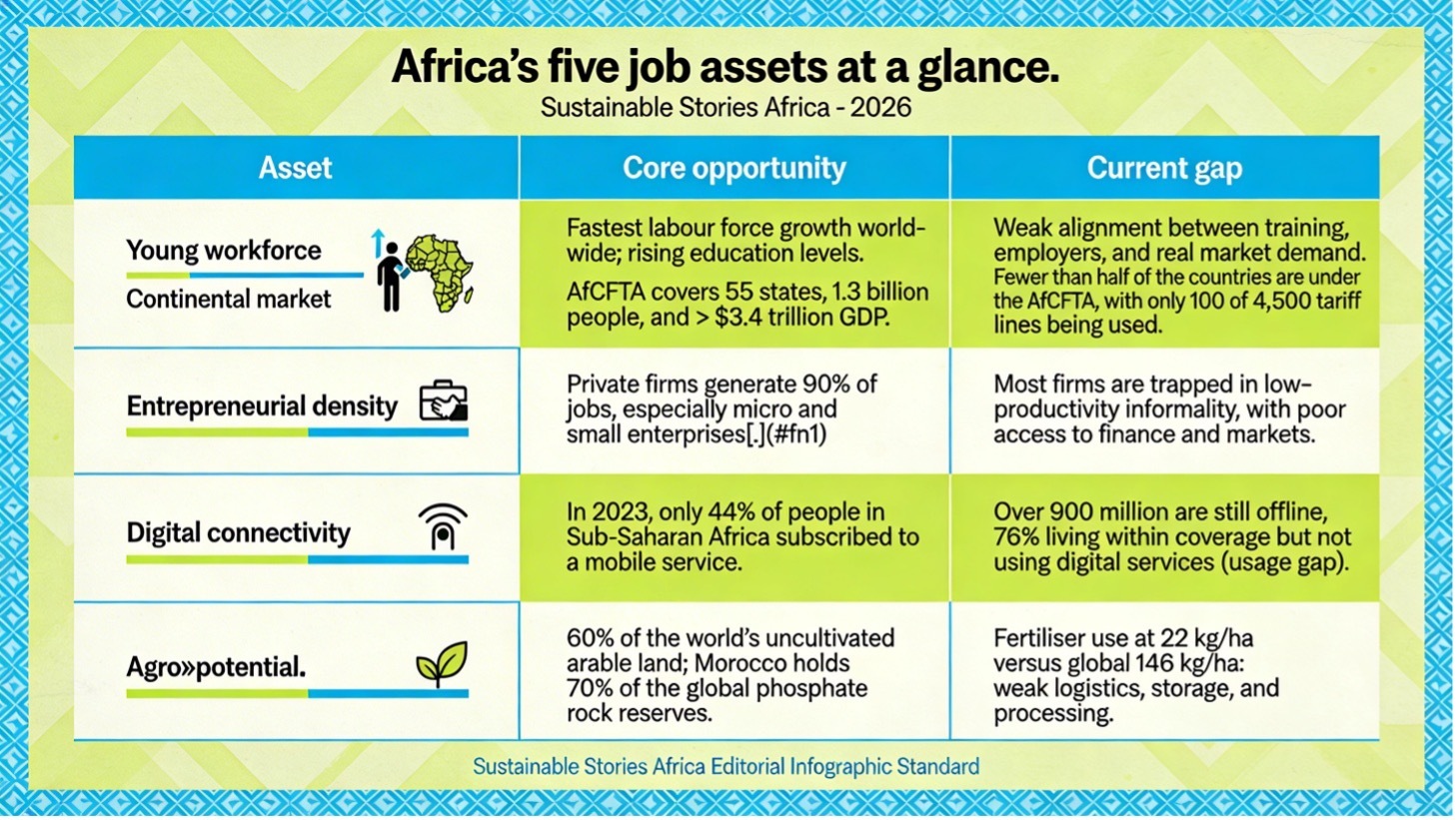

Five assets, one underutilised jobs engine

The Foresight Africa analysis distils the job opportunities into five concrete assets.

Africa’s five job assets at a glance

| Asset | Core opportunity | Current gap |

|---|---|---|

| Young workforce | Fastest labour force growth worldwide; rising education levels. | Weak alignment between training, employers, and real market demand. |

| Continental market | AfCFTA covers 55 states, 1.3 billion people, and > $3.4 trillion GDP. | Fewer than half of the countries are actively trading under the AfCFTA, with only 100 of 4,500 tariff lines being used. |

| Entrepreneurial density | Private firms generate 90% of jobs, especially micro and small enterprises. | Most firms are trapped in low‑productivity informality, with poor access to finance and markets. |

| Digital connectivity | In 2023, only 44% of people in Sub-Saharan Africa subscribed to a mobile service. | Over 900 million are still offline, 76% living within coverage but not using digital services (usage gap). |

| Agro‑potential | 60% of the world’s uncultivated arable land; Morocco holds 70% of the global phosphate rock reserves. | Fertiliser use at 22 kg/ha versus global 146 kg/ha: weak logistics, storage, and processing. |

These assets are not theoretical. AfCFTA offers a platform for a 1.3‑billion‑person integrated market, with strong intra-African demand already visible in agro-processing, logistics, light manufacturing, and tradable services.

Private firms already create approximately 90% of Africa’s jobs, even if most are small and constrained by infrastructure and finance. Mobile subscriptions reached approximately 527 million people by 2023, while digital commerce is central to propel benefits up to 80 million young Africans by 2030.

Agriculture, still the largest employer, offers opportunities for yield gains, value additions, and rural industrialisation, from fertiliser to cold chains to processing clusters.

Where the system is breaking down

The analysis is blunt about why these strengths are not translating into mass, decent jobs.

- Training systems focus on access, not employability; firms complain of skills gaps while graduates struggle to find work.

- AfCFTA is ratified but underused; fewer than half of member states were trading under its preferences as of late 2025.

- Informality is treated as a nuisance to be registered away, rather than a productivity problem to be solved with bundled support, digital rails, procurement ladders, and basic business services.

- Digital divides are less about coverage than affordability, skills, and relevant services; 76% of Africans live under a mobile signal but cannot or do not use data services.

- Agro‑systems are starved of inputs, storage, and processing capacity; Africa’s fertiliser use is one‑seventh of the global average, while post‑harvest losses remain high.

In short, the ingredients of a jobs engine exist, but they sit in silos, separated by policy fragmentation, weak infrastructure, and thin coordination.

From fragmented projects to connected pathways

The report’s most compelling contribution is to highlight how these assets can reinforce each other if policy is sequenced around corridors, markets and people rather than sectors alone.

- Skills to careers, not just classrooms – skill‑to‑career compacts would tie curricula, training providers and employers to clear competency standards, apprenticeships and verified placement outcomes, shifting incentives from enrolment to employability.

- Corridors rather than isolated industrial parks – AfCFTA corridors, where transport, energy, logistics, customs and skills investments are layered together, can create “good jobs zones” that allow firms to scale, specialise and pay better wages.

- Upgrading informality into productivity – Digital IDs, e‑payments, and e‑invoicing can help micro‑enterprises build transaction histories, access credit, and climb “procurement ladders” from micro‑contracts to larger tenders.

- Digital jobs with protections – With online gig work already accounting for up to 12% of labour in emerging economies, and with Sub‑Saharan Africa experiencing the fastest growth rate in postings, a basic quality framework, skills, fair pay rules, grievance channels and portable social protection can turn precarious gigs into stepping stones.

- Agro‑industry is a mass employer – Smarter fertiliser blends, better distribution, expanded irrigation, cold chains and processing clusters tied to economic corridors can simultaneously lift farm incomes and create off‑farm wage jobs in storage, logistics and food processing.

Taken together, this is not a call for one more youth strategy, but for a different development logic: use integration and technology to turn Africa’s vast informal and rural economies from subsistence to scale.

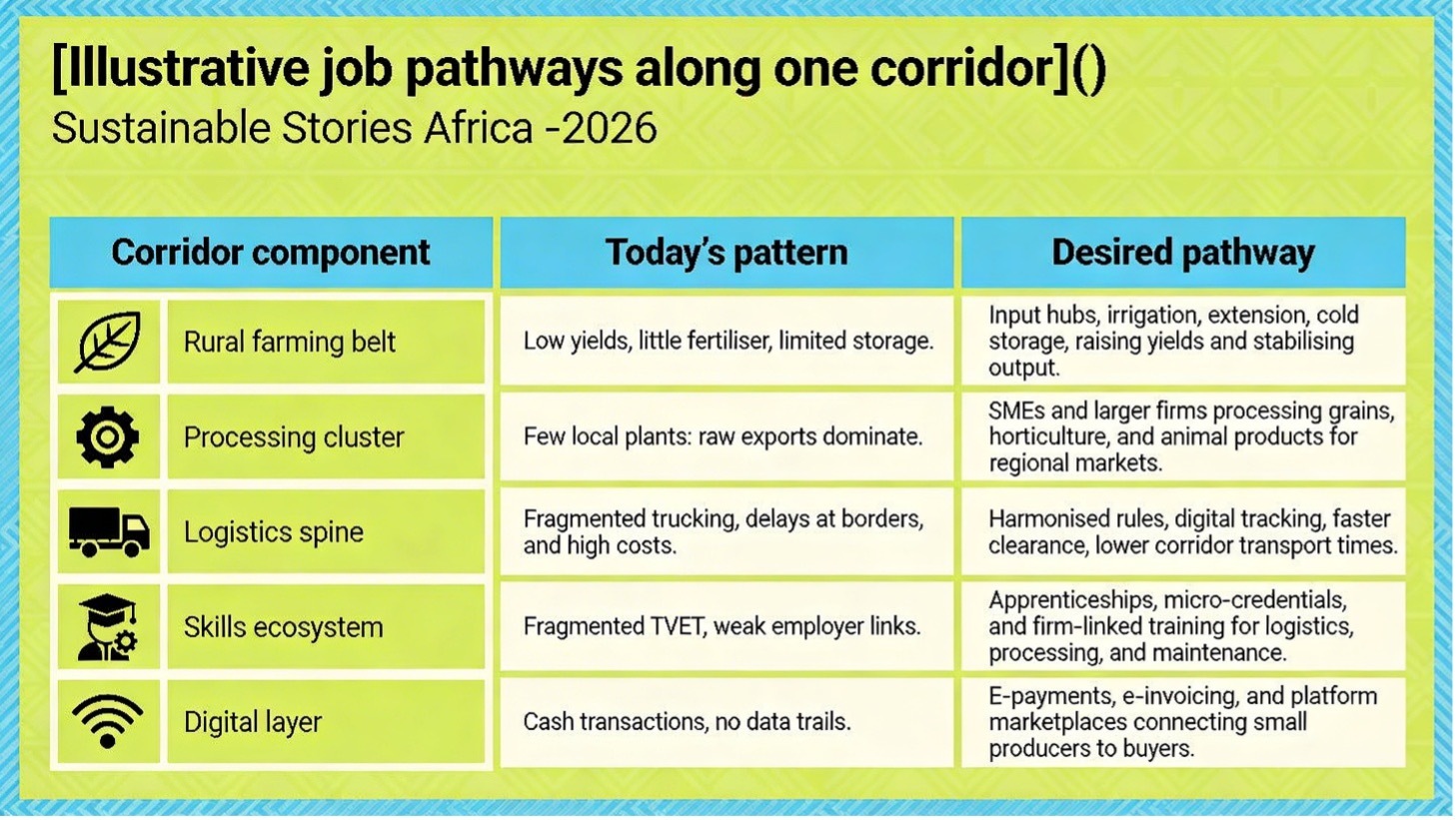

Illustrative job pathways along one corridor

| Corridor component | Today’s pattern | Desired pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Rural farming belt | Low yields, little fertiliser, limited storage. | Input hubs, irrigation, extension, cold storage, raising yields and stabilising output. |

| Processing cluster | Few local plants: raw exports dominate. | SMEs and larger firms processing grains, horticulture, and animal products for regional markets. |

| Logistics spine | Fragmented trucking, delays at borders, and high costs. | Harmonised rules, digital tracking, faster clearance, lower corridor transport times. |

| Skills ecosystem | Fragmented TVET, weak employer links. | Apprenticeships, micro‑credentials, and firm‑linked training for logistics, processing, and maintenance. |

| Digital layer | Cash transactions, no data trails. | E‑payments, e‑invoicing, and platform marketplaces connecting small producers to buyers. |

Such corridors won’t solve everything. However, they offer a tangible way to bundle reforms, investment and learning in places where they compound, rather than adding scattered pilot projects to an already crowded landscape.

What must leaders, businesses and partners do?

The Foresight analysis provides insights into a simple yet demanding message: Africa does not need more declarations; it needs a few hard choices, held over time.

Four decisions that will determine whether Africa’s youth dividend pays out

- Rewire education around employability – Governments and employers should design skill‑to‑career compacts, fund apprenticeships at scale, and publish placement and earnings outcomes so young people can see which programmes actually lead to work.

- Make AfCFTA a reality along specific corridors – Rather than treating integration as a legal exercise, countries can select high-potential corridors and sectors, such as agro‑processing, light manufacturing and tradable services, and align infrastructure, customs, regulations and investment promotion around them.

- Treat informality as an upgrading agenda – Rather than one-off registration drives, ministries can partner with fintechs, business associations and city authorities to roll out digital rails, procurement ladders and basic business services for micro-enterprises.

- Embed job quality in digital and agro strategies – Digital‑economy plans and agricultural transformation strategies should be judged not just by GDP or export numbers, but by how many decent, protected jobs they create for young women and men.

None of this will be easy, and the window is not indefinite. However, the story is not yet written. Africa’s five assets already exist; the question is whether leaders will connect them fast enough to turn demographic pressure into a workforce dividend, rather than a generation of disappointment.

Path Forward – Connecting assets into dignified work

Africa’s youth surge, continental market, vibrant firms, digital rails and agricultural base can become a single jobs engine if leaders transition from fragmented projects to corridor-based and market‑shaping strategies that reward productivity and inclusion.

The priority now is to rewire skills systems, enforce AfCFTA along key corridors, upgrade informality with digital tools and procurement ladders, and embed job quality in digital and agro‑industrial plans.