Aid is shrinking just as Africa’s investment needs and debt pressures intensify, forcing a hard reset. The new development playbook is less about pleading for concessional flows and more about mobilising domestic resources: taxes, natural capital, diaspora giving, and credibility in global capital markets.

If Africa gets the mix right, value addition, transparent contracts, and better ratings, today’s crunch can become tomorrow’s sovereignty dividend. If it doesn’t, the financing gap will continue to turn budgets into a means of survival.

Africa’s new development math in 2026

Picture a finance ministry team, late-night spreadsheets open, trying to stretch public money across roads, power, health, and jobs, while donor envelopes arrive smaller than last year’s.

That’s the lived policy reality behind Brookings’ Foresight Africa 2026 MOBILIZING AFRICA’S RESOURCES FOR DEVELOPMENT Section: sub-Saharan Africa needs at least $245 billion in additional financing each year, even as external funding tightens and debt service crowds out social spending.

The shift is not merely fiscal; it is the centre of political economy. Africa can either convert its natural wealth, tax capacity, and diaspora ties into predictable development finance or remain exposed to volatile aid cycles, punitive borrowing costs, and resource extraction that fails to build shared prosperity.

Aid retreat meets Africa’s capital crunch

Africa enters 2026 with resilience, but not enough financing to match its ambitions. Sub-Saharan Africa was projected to grow at approximately 4.1% in 2025, with minimal growth in 2026; however, the region still faces a financing gap averaging $245 billion annually.

The pressure is amplified by a contraction of aid historically. Official development assistance fell 9% in 2024 and was projected to decline between 9% and 17% in 2025, particularly due to the dissolution of USAID and other donor cutbacks.

Meanwhile, expensive capital and rising distress are shrinking policy room: more than 50% of Africa’s low-income countries are in, or at high risk of, debt distress, and annual debt-service spending in the region exceeded $101 billion in 2025, money that competes directly with health, education, and social protection.

Here’s the uncomfortable headline for sustainability analysts: Africa’s development constraints are no longer primarily technical; they are increasingly about who controls capital, how risk is priced, and whether natural wealth is transformed into durable public value rather than exported as raw rent.

How the financing gap is widening

The report’s diagnosis is blunt: domestic savings in sub-Saharan Africa have averaged under 20% of GDP, investment has hovered just over 20% of GDP, which is below the roughly 30% investment rate often needed to finance development over time.

External financing cannot substitute the difference, as it increases volatility and can intensify current-account stress, balance-of-payments risk, and debt vulnerabilities, especially in an era of higher interest rates and risk aversion.

So, the financing debate turns inward, toward three domestic levers with outsized relevance for ESG-minded development:

- Tax capacity and governance

- Plugging illicit leakages

- Turning natural capital into investable public wealth.

On taxation, Brookings notes a structural gap: sub-Saharan Africa’s taxation capacity is around 20% of GDP; however, tax revenues average about 15% of GDP, partly due to informality and narrow bases.

Governance reforms, including anti-corruption, transparency, and stronger revenue administration, could raise revenues by 3.9 percentage points, increasing capacity and mobilising almost $94 billion on average over five years.

On leakages, UNCTAD estimates Africa loses around $90 billion annually through illicit financial flows, an argument for coordinated action on multinational tax avoidance and fairer global tax rules (via efforts like the OECD Inclusive Framework and the UN tax cooperation process).

And then there is the continent’s biggest balance-sheet item: sub-Saharan Africa’s natural resource wealth was estimated at over $6 trillion in 2020, with renewables valued at around $5.17 trillion and non-renewables at around $840 billion, amounts suggested to be greatly undervalued given recent discoveries.

Turning natural wealth into public value

The opportunity is not extraction; it is conversion. Africa holds at least 30% of the proven reserves of critical minerals; however, much is exported with limited local value addition, which reduces job opportunities, learning, and fiscal benefits.

The report highlights the scale of the potential mineral revenue cycle: the IMF estimates that global revenues from extracting copper, nickel, cobalt, and lithium could total $16 trillion over 25 years, with sub-Saharan Africa positioned to capture over 10%, nearly $2 trillion.

However, the report highlights a climate-finance realism that many global narratives avoid: Africa holds 7.2% of proven oil reserves and 7.5% of proven gas reserves and contributes between 3% and 4% of global CO2 emissions despite accounting for 20% of the world’s population.

That asymmetry underpins a proposed “dual track” approach, which involves developing some fossil resources and reinvesting a share of the proceeds into renewables, especially as renewables (solar, wind, hydropower, geothermal) could supply over 80% of new power generation capacity; however, financing constraints slow deployment.

The governance subtext is just as important as the energy mix: poorly negotiated contracts and weak oversight have historically limited public returns. The report highlights estimated annual losses of between $470 and $730 million in corporate tax revenues from profit shifting in the mining sector alone.

Beyond minerals and energy, the financing story becomes institutional: sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) can convert nonrenewable revenues into long-term financial assets, and sub-Saharan Africa’s existing SWFs hold around $100 billion in assets under management; however, many resource-intensive countries still lack them.

What leaders must do in 2026

- First, treat domestic resource mobilisation as a delivery agenda, not a slogan: scale tax compliance and administration while protecting equity, because the gap between 15% revenue and 20% capacity is real money that can fund human capital and infrastructure.

- Second, renegotiate the “resource bargain” around transparency and value addition, progressive fiscal terms, public reporting, and enforcement, so price booms translate into budgets, local procurement, and investable infrastructure, not just offshore rents.

- Third, convert diaspora affinity into structured capital: the report frames diaspora philanthropy as a resilient channel, including cash, goods, skills, and knowledge for social benefit and notes donor cuts are pushing countries to diversify flexible social-sector financing.

It also highlights practical tools (used elsewhere) that African governments can adapt with trust-building: matching-grant models (e.g., Mexico’s 3x1, Moldova’s PARE 1+1), diaspora bonds (successful in Israel and India), and collective giving platforms, while acknowledging persistent roadblocks like weak information, platform trust deficits, and restrictive ecosystems.

- Fourth, lower the “Africa risk premium” with data and strategy, not indignation: the sovereign credit ratings viewpoint notes that since UNDP’s early efforts, 34 African countries have been rated and 21 countries have raised $155 billion through Eurobonds; however, only three are investment grade as of end-October 2025.

The UNDP also estimates that 16 African countries pay more in debt service than they should, as their ratings are lower than they could be. This amounts to an estimated loss of over $74 billion, highlighting that the potential benefits of ratings reform, improved data, and credible macroeconomic frameworks can translate into fiscal space.

- Finally, back African-led architecture to change the rules: the viewpoint urges support for the African Union’s Africa Credit Ratings Agency (AfCRA), alongside stronger in-country capacity and more context-fit methodologies by global ratings agencies.

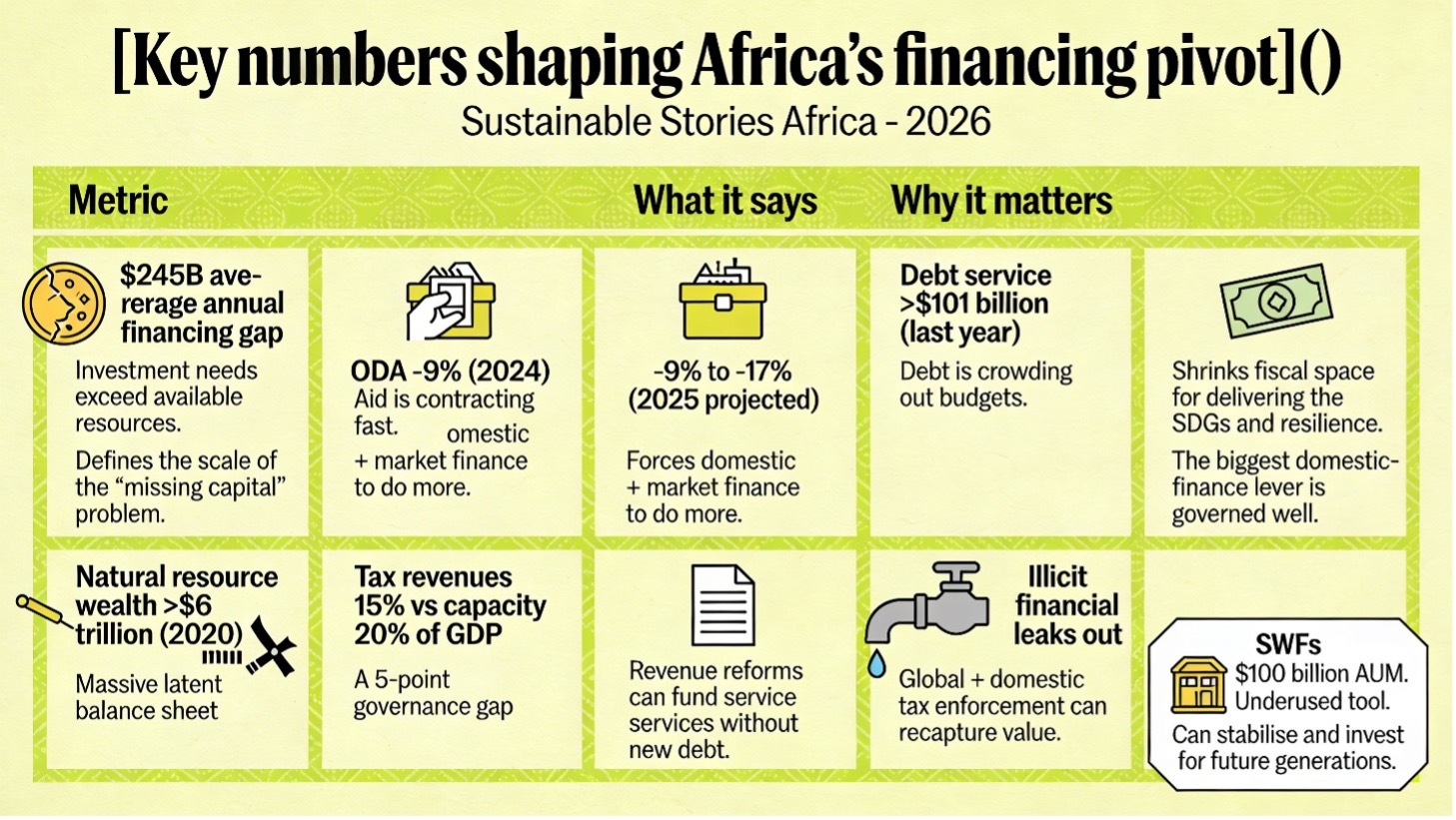

Key numbers shaping Africa’s financing pivot

| Metric | What it says | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| $245B average annual financing gap | Investment needs exceed available resources. | Defines the scale of the “missing capital” problem. |

| ODA -9% (2024), -9% to -17% (2025 projected) | Aid is contracting fast. | Forces domestic + market finance to do more. |

| Debt service >$101 billion (last year) | Debt is crowding out budgets. | Shrinks fiscal space for delivering the SDGs and resilience. |

| Natural resource wealth >$6 trillion (2020) | Massive latent balance sheet | The biggest domestic-finance lever is governed well. |

| Tax revenues 15% vs capacity 20% of GDP | A 5-point governance gap | Revenue reforms can fund services without new debt. |

| Illicit financial flows $90 billion/year | Money leaks out | Global + domestic tax enforcement can recapture value. |

| SWFs $100 billion AUM | Underused tool | Can stabilise and invest for future generations. |

Path Forward – Five moves to finance Africa’s future

Cut the leakage: raise tax collection toward capacity, curb illicit flows, and publish resource contracts. Turn extraction into transformation: negotiate progressive terms, invest in local processing, and reinvest proceeds into renewable buildout.

Build credibility: by strengthening data systems for ratings, expanding SWFs with independent oversight, and structuring diaspora capital through trusted platforms and instruments.

Align all three with one test; does it create fiscal space and decent jobs without sacrificing resilience?