By Omid Hamidkhani – Alternative Fuels Development Consultant

Nigeria's transition from PMS to Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) is more than a fuel switch; it is a structural reform shaped by subsidy removal, rising fuel costs and the search for cleaner, locally sourced energy solutions.

However, the long-term success of this transition will not be determined by only economics. It will depend on one decisive factor: public confidence anchored in safety standards, inspection discipline and institutional enforcement.

CNG Reform Tests Governance and Trust

Nigeria's shift from PMS to Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) has emerged as one of the most consequential reforms in its evolving energy landscape. With the removal of fuel subsidy and rising PMS prices reshaping transport economics, policymakers face both pressure and opportunity: to deliver a cleaner, more affordable and locally available alternative.

CNG presents a compelling case. Nigeria holds abundant natural gas reserves and is expanding its distribution infrastructure. If executed properly, the reform could lower transport costs, reduce emissions and stimulate industrial activity across the value chain.

However, like any systemic energy transition, its durability will depend not merely on resource availability, but on governance, safety enforcement and sustained public trust.

Subsidy Reform Creates Structural Opening

The removal of the PMS subsidy has altered Nigeria's fuel economics in a way that makes CNG adoption not just desirable, but necessary. The fiscal burden of sustaining large subsidy payments could no longer continue indefinitely.

This policy shift has created a window for reform, one that aligns affordability, environmental responsibility and domestic resource utilisation.

CNG offers:

- Lower operating costs for transport users

- Reduced emissions

- Domestic energy security

- Industrial value-chain expansion

Nigeria is structurally positioned to lead Africa's cleaner mobility shift, if the transition is executed with discipline.

The Engine Analogy – Policy as Spark

The national CNG rollout resembles the operation of an internal combustion engine. An engine requires ignition to operate independently.

In the same way, CNG adoption requires an initial spark, provided by the government through:

- Early incentives

- Clear policy direction

- Infrastructure investment

- Institutional coordination

Once momentum builds, private investors, fleet operators and vehicle owners begin to scale the market organically. Over time, state intervention reduces as the market becomes economically self-sustaining.

This ignition phase is decisive. Poor design at the beginning can stall adoption; disciplined implementation can create compounding growth.

Safety Determines Public Acceptance

Economic logic alone will not drive mass adoption. Public confidence is foundational.

The recurring question remains: "Is it really safe?"

International experience provides evidence. During a 2005 aeroplane crash incident in Tehran, a CNG bi-fuel vehicle exposed to extreme heat did not explode.

|  |

Photo: Aftermath of an aeroplane crash in Iran (2005). A CNG vehicle nearby remained intact; the cylinder's safety device functioned properly, preventing any explosion or rupture.

Its Pressure Relief Device (PRD) activated correctly, venting gas safely and preventing rupture. The system functioned exactly as international safety standards intended.

This real-world example to show a fundamental principle: Standard-compliant CNG systems are inherently safe, even under catastrophic conditions.

For Nigeria, the policy implication is clear: safety compliance must not be optional or diluted during rapid rollout.

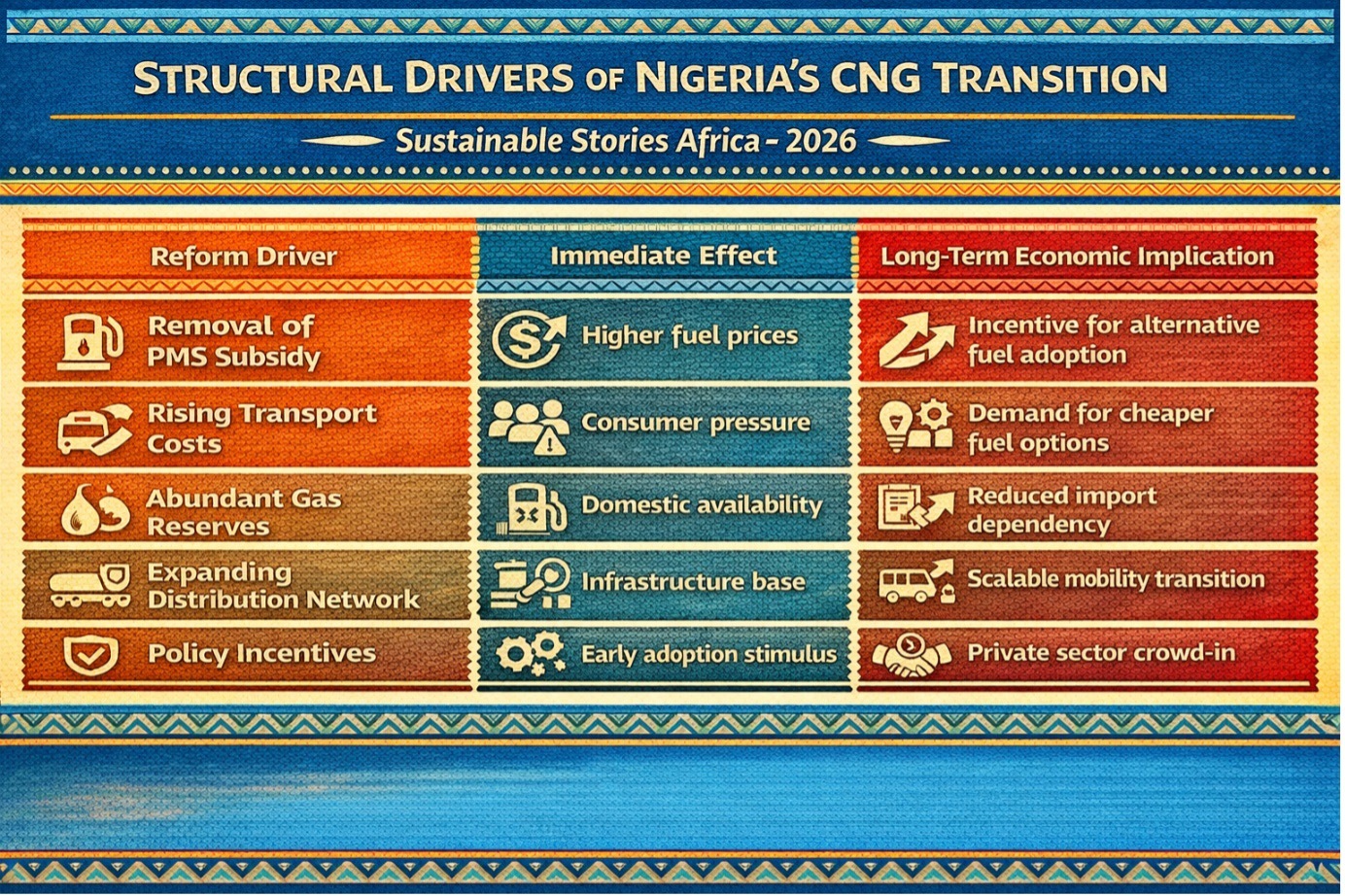

Structural Drivers of Nigeria's CNG Transition

| Reform Driver | Immediate Effect | Long-Term Economic Implication |

|---|---|---|

| PMS Subsidy Removal | Higher fuel prices | Incentive for alternative fuel adoption |

| Rising Transport Costs | Consumer pressure | Demand for cheaper fuel options |

| Abundant Gas Reserves | Domestic availability | Reduced import dependency |

| Expanding Distribution Network | Infrastructure base | Scalable mobility transition |

| Policy Incentives | Early adoption stimulus | Private sector crowd-in |

Standards, Inspection and Enforcement

Using certified kits and cylinders is necessary, but not sufficient.

Periodic inspection and re-testing are mandatory under international standards and manufacturer recommendations, particularly for CNG cylinders.

Corrosion creates a significant risk in humid environments such as Nigeria. A cylinder that is safe at installation can deteriorate over time without proper inspection and calibration.

The documented example of a severely corroded cylinder resulting from a lack of periodic inspection underscores the risk of complacency.

Key safety pillars include:

- Internationally certified components

- Traceable installation processes

- Mandatory periodic inspections

- Certified re-testing cycles

- Regulatory enforcement mechanisms

Without these measures, isolated safety failures could undermine public confidence and stall adoption entirely.

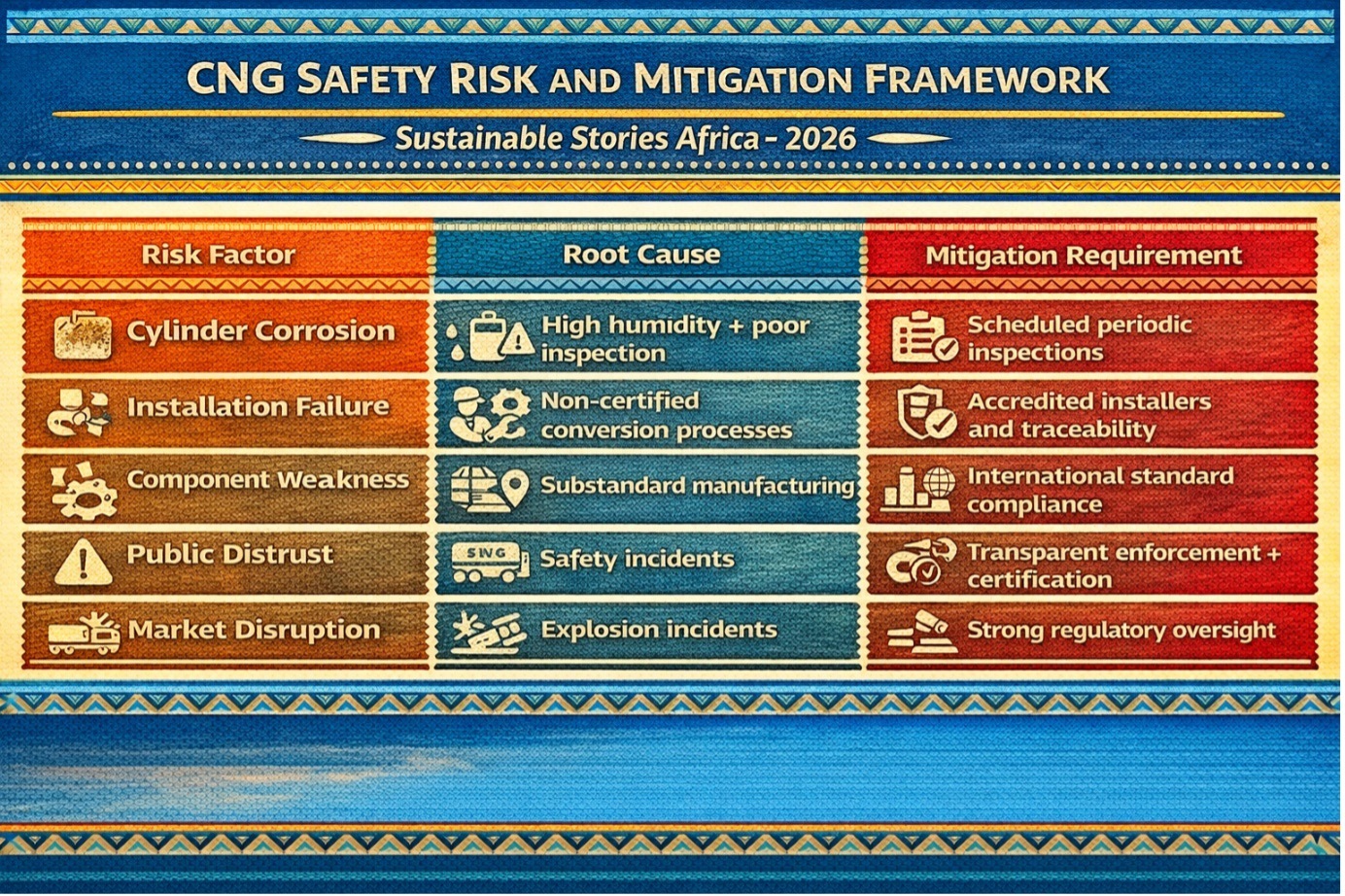

CNG Safety Risk and Mitigation Framework

| Risk Factor | Root Cause | Mitigation Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| Cylinder Corrosion | High humidity + poor inspection | Scheduled periodic inspections |

| Installation Failure | Non-certified conversion processes | Accredited installers and traceability |

| Component Weakness | Substandard manufacturing | International standard compliance |

| Public Distrust | Safety incidents | Transparent enforcement + certification |

| Market Disruption | Explosion incidents | Strong regulatory oversight |

Path Forward – Ignite Growth Through Enforced Safety Discipline

Nigeria's government and private sector have made commendable strides in accelerating rollout initiatives for CNG. The direction is clear and economically rational.

However, long-term success will depend on consistent enforcement of safety standards, strict quality assurance of components and conversion processes, and timely periodic inspections.

If safety precautions are neglected and incidents occur, public confidence will erode quickly. Economic advantages alone cannot restore trust once it is compromised.

The CNG transition represents a pivotal opportunity for Nigeria's energy reform agenda. But like the engine analogy that defines its rollout, without proper ignition and disciplined maintenance, performance may not be sustained.

Safety is not a technical footnote. It is the ignition point of the entire reform.