Artificial intelligence is increasing much faster than any technology before it. However, history tells us that what happens next is rarely neutral.

AI choices will redraw Africa's future

The Industrial Revolution did not merely introduce steam engines. It redrew the map of prosperity. As the UNDP's The Next Great Divergence Report (Part 1) reminds us, by the late nineteenth century, life expectancy in early industrial economies increased, while in colonised regions it dramatically declined.

The twentieth century then brought a partial "Great Convergence," driven by the diffusion of medicine, education, and global trade.

Today, artificial intelligence presents a similar structural inflexion point.

While the report centres on the Asia-Pacific, its diagnosis of uneven technological diffusion is deeply relevant to Africa.

The continent enters the AI era with profound internal diversity: tech hubs in Nairobi, Lagos, Cape Town, and Cairo coexist with regions still struggling with reliable electricity and broadband.

The lesson from history is clear: technology does not equalise on its own. It amplifies existing institutional strength or fragility.

The Next Divergence May Be Digital

Part 1 of the UNDP report traces how transformative technologies historically generated both divergence and convergence. Steam power, electricity, containerization, and the internet first rewarded early adopters with capital and institutional depth.

Artificial intelligence, described as a new "general-purpose technology", may follow the same arc, only faster.

Africa must confront a difficult possibility: AI could increase global abundance while concentrating its gains among digitally prepared economies.

In 1800, global income gaps were relatively modest. By 1950, the life expectancy gap between Norway and Afghanistan had reached nearly half a century. Divergence unfolded gradually, then became entrenched.

AI's timeline is compressed.

The question is whether Africa enters this wave as a participant or as a dependent consumer of imported intelligence.

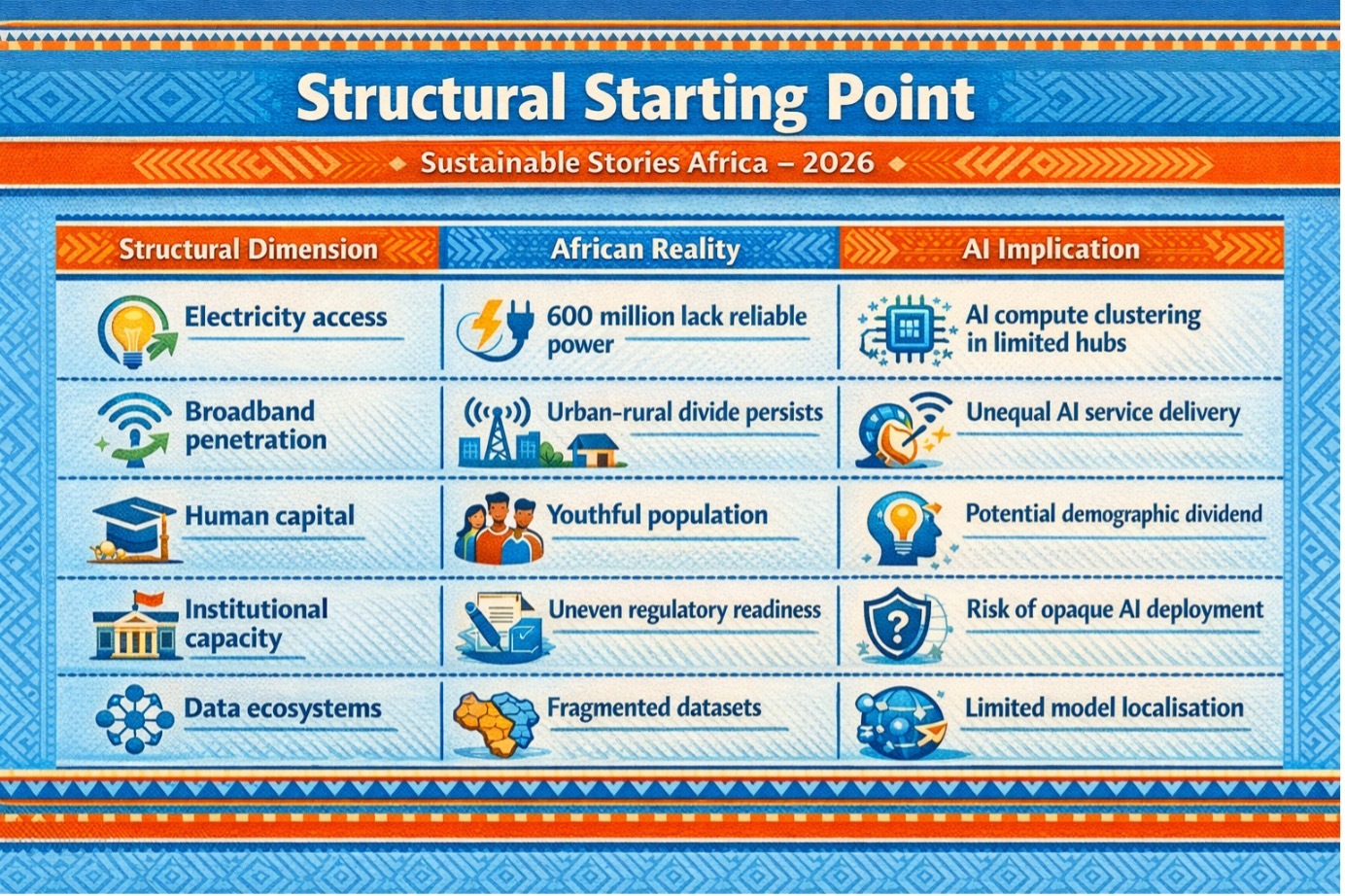

Structural Starting Points Matter

The report emphasises that technological revolutions reward early investment in infrastructure, skills, and governance.

Africa's structural baseline presents both strengths and vulnerabilities:

Structural Starting Point

| Structural Dimension | African Reality | AI Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity access | 600 million lack reliable power | AI compute clustering in limited hubs |

| Broadband penetration | Urban-rural divide persists | Unequal AI service delivery |

| Human capital | Youthful population | Potential demographic dividend |

| Institutional capacity | Uneven regulatory readiness | Risk of opaque AI deployment |

| Data ecosystems | Fragmented datasets | Limited model localisation |

History shows diffusion narrows gaps only when institutions adapt.

The report's analysis of within-country inequality, where the top 10% capture disproportionate gains, should resonate strongly in Africa. In many economies, digital wealth is already concentrated in urban spaces.

Without intervention, AI could reinforce:

- Urban over rural inclusion

- Large firms over SMEs

- Skilled labour over informal workers

- Imported models over local datasets

Africa risks what might be termed "algorithmic peripheralization."

What Convergence Could Look Like

But history also offers hope.

The diffusion of vaccines, literacy, and trade networks ignited the twentieth century's Great Convergence. Technology eventually spread, but only after a deliberate public investment.

Imagine an African AI strategy grounded in inclusion:

- AI-assisted diagnostics in rural clinics, reducing TB and maternal mortality

- Local-language tutoring systems expanding literacy

- Climate forecasting models improving drought resilience

- Credit scoring innovations expanding SME financing

- Agricultural advisory systems increasing yields

In Lagos, a fintech founder recently noted: "Our biggest barrier isn't innovation. It's infrastructure and trust."

That insight mirrors the report's central framing: technology is not destiny. Policy choices determine distribution.

Convergence requires intentional diffusion.

Five Strategic Imperatives for Africa

Drawing from the historical lessons outlined in Part 1, Africa's AI pathway should rest on five priorities:

- Invest in Hard Foundations – Electricity, fibre, cloud infrastructure, and local data centres are prerequisites, not luxuries.

- Build Soft Capacity in Parallel – AI literacy, regulatory capacity, and institutional readiness must align with investments in hardware.

- Prevent Data Colonisation – African datasets should be governed locally, with clear standards on consent, sovereignty, and access.

- Align AI with Development Strategy – AI must support national priorities, such as agriculture, health, and financial inclusion, rather than abstract innovation targets.

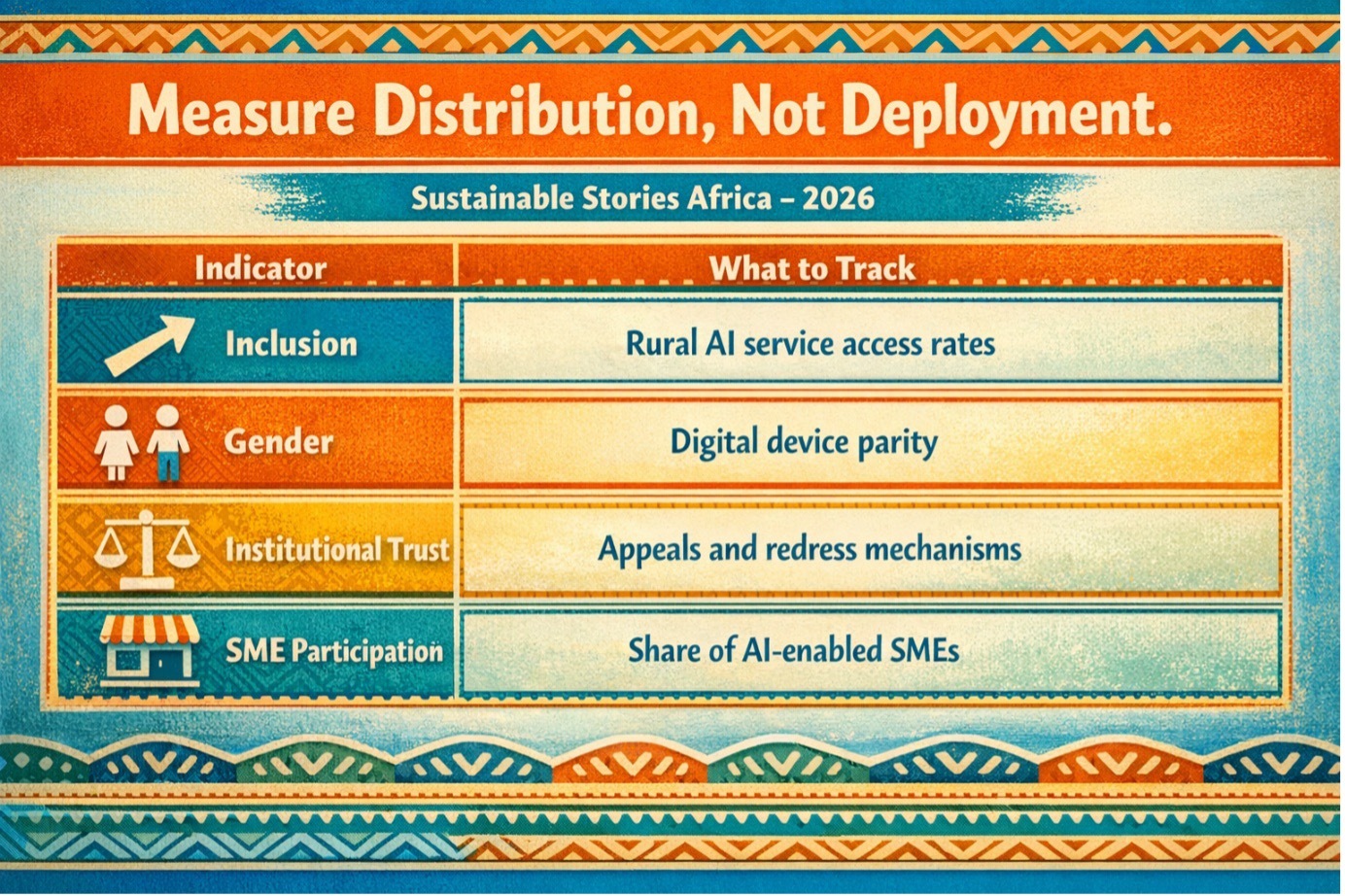

Measure Distribution, Not Deployment

| Indicator | What to Track |

|---|---|

| Inclusion | Rural AI service access rates |

| Gender | Digital device parity |

| Institutional trust | Appeals and redress mechanisms |

| SME participation | Share of AI-enabled SMEs |

Deployment numbers alone do not equal development. Distribution metrics define justice.

PATH FORWARD – Choose Convergence Before Code Hardens

Africa is not condemned to technological marginalisation. However, neither is inclusion automatic.

The Industrial Revolution widened gaps before they narrowed. AI will move faster. The window for shaping outcomes is shorter.

If African leaders treat AI as public infrastructure, governed with transparency, inclusion, and sovereignty, the continent can compress development timelines.

If not, the next great divergence may be digital. The choice is political. The clock is technological.