The Gambia is growing again, but its public debt story is far from over. Debt has fallen from its pandemic-era peak; however, key indicators still flash red, and every dalasi spent on interest is one less for clinics, classrooms or climate resilience.

With external debt service expected jump from 2025, the country stands at a crossroads: either deepen reforms that turn debt into development or slip back into a cycle where borrowing quietly strangles future growth.

Debt Relief Gains, New Risks Rising

Public debt in The Gambia has been reducing, but remains at the heart of the country's economic vulnerability. Total public debt reduced by 14.42% from 83.2% of GDP in 2022 to 71.2% in 2024, helped by stronger domestic revenue and lower net domestic borrowing.

However, the country is classified as high risk of external and overall debt distress, with service obligations consuming a significant proportion of public resources. This is according to the World Bank Group Spring 2025 report – The Gambia Public Debt: An Achilles Heel?

The real pressure point commenced in 2025, when external debt service deferrals expired, and foreign payments are projected to increase from 2.0% of GDP in 2024 to an average of 2.7% in 2025–2028.

Forecasts suggest this alone could shave around 1.2 percentage points off annual growth over the period, effectively taxing the future to pay for yesterday's bills.

A Decade Of Borrowing, A Narrower Fiscal Path

Over the past decade, The Gambia has heavily favoured borrowing to fund development because households and the tax system have not generated enough savings to meet its ambitions.

From 1966 to 2023, domestic savings averaged 4% of GDP, compared with 17.4% for Sub-Saharan Africa and 11% for ECOWAS, while investment hovered around 15% GDP, also below regional benchmarks.

Tax revenues have also lagged, averaging 10.2% of GDP between 2017 and 2023, well below the 15% "tipping point" generally believed to be the minimum for critical public investments.

Combined with rigid spending, Gambia has witnessed an average fiscal deficit of 4.7% of GDP over the period, close to the ECOWAS average but above Sub‑Saharan Africa, and this has pushed the government to borrow heavily at home and abroad.

When Debt Crosses The Growth Red Line

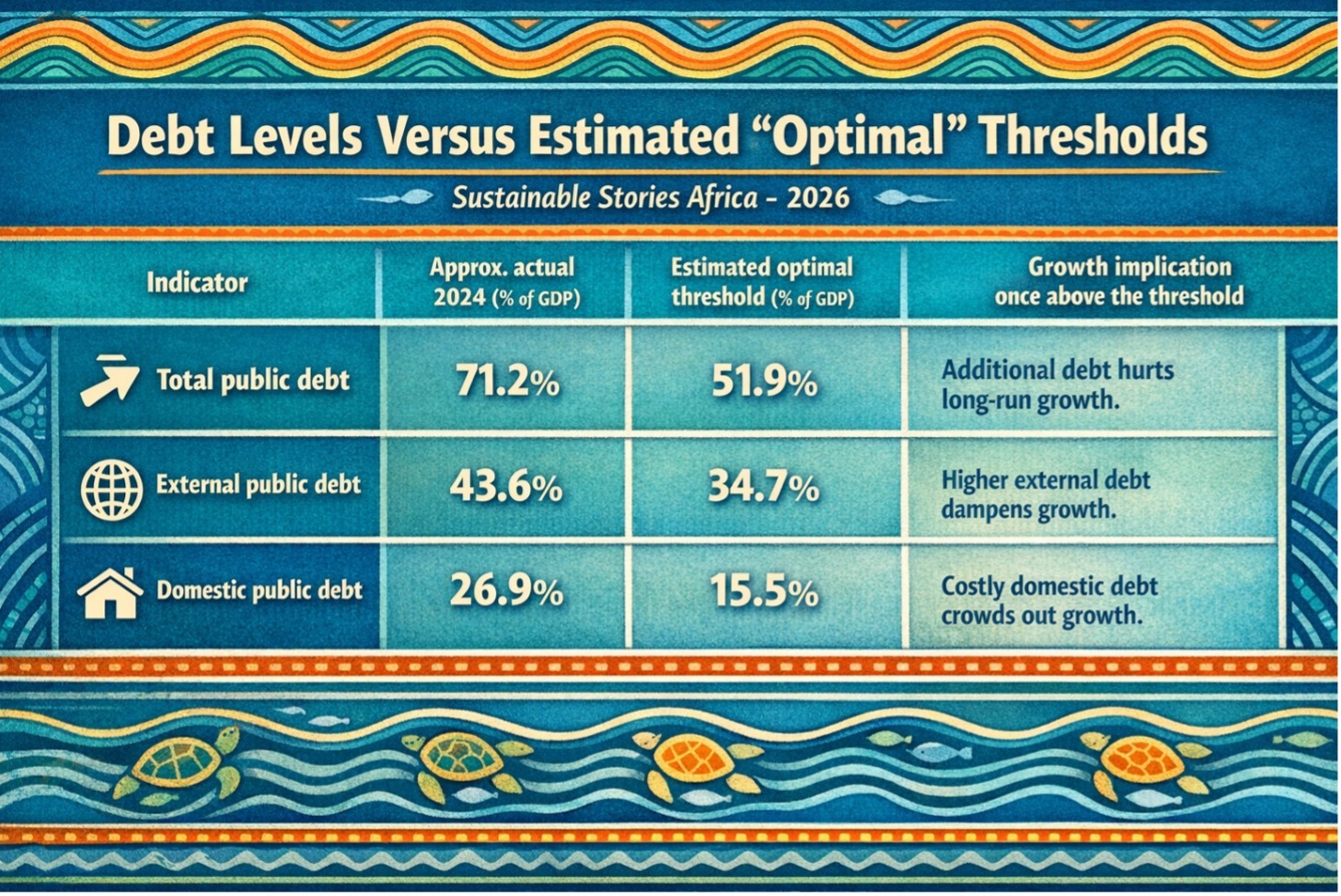

The report's most sobering conclusion is numerical: beyond certain thresholds, The Gambia's public debt ceases to support growth and starts to undermine it.

Debt Levels Versus Estimated "Optimal" Thresholds

| Indicator | Approx. actual 2024 (% of GDP) | Estimated optimal threshold (% of GDP) | Growth implication once above the threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total public debt | 71.2% | 51.9% | Additional debt hurts long‑run growth. |

| External public debt | 43.6% | 34.7% | Higher external debt dampens growth. |

| Domestic public debt | 26.9% | 15.5% | Costly domestic debt crowds growth. |

At moderate levels, public borrowing can lift growth by financing infrastructure and supporting recovery; beyond those thresholds, the marginal effect turns negative as interest costs rise and investment is crowded out.

Debt service ratios are already above standard sustainability benchmarks, with external debt service to revenue reaching 31.9% in 2023, beyond the 18% to 23% range commonly used for high‑risk countries.

Domestic debt, mostly held by commercial banks, accounts for 80% of total interest payments despite being only a third of the debt stock, reflecting higher local interest rates. That tilt makes borrowing at home particularly expensive and leaves less room to finance productive private activity.

How Debt Chokes Investment, Credit and Jobs

Debt affects the Gambian economy through three main transmission channels: public investment, private investment and interest rates.

- High debt servicing costs averaging around 6.5% of GDP between 2021 and 2024 – have constrained fiscal space, with domestic debt service alone consuming roughly 23% of the domestically financed budget, nearly matching combined health and education allocations.

- Research summarised in the report suggests that when total public debt rises above between 71% and 72% of GDP, both public and private investment are adversely affected, as uncertainty and higher rates discourage capital formation.

- Banks, holding government securities that are safe and lucrative, have fewer incentives to lend long‑term to businesses, weakening financial deepening, limiting job‑creating investment and reinforcing a "lazy banking" equilibrium.

Climate shocks add a further twist to the debt–growth story. Severe flooding in 2022 affected over 50,000 people and caused an estimated $80 million in damage. Modelling studies suggest real GDP growth can remain between 2% and 3.1% below pre‑disaster levels for up to five years after major events.

Each shock pushes up emergency spending, undermines revenue and quietly reloads fiscal risks, often financed by more borrowing.

What's Driving The Debt Dependence?

Beneath the debt ratios lies a structural financing problem.

- Savings and revenue gaps – With households struggling on per capita incomes of $861 in 2023, most income goes to basic consumption, limiting formal savings and taxable capacity.

- Low domestic revenue and high grant dependence – Domestic revenue rose from 12.5% of GDP in 2023 to 14.0% in 2024; however, grants accounted for a third of total revenues between 2017 and 2023, with 80% of capital spending externally financed.

- Loss‑making state‑owned enterprises (SOEs) – Budget support to SOEs reached an estimated 5% of GDP in 2020, while net arrears to the government were 3.6% of GDP, forcing repeated bailouts, particularly in the energy sector.

- Trade and price shocks – A narrow export basket and volatile import prices widened the merchandise trade deficit by 168.46% from 14.9% of GDP in 2002 to almost 40% in 2022, much of it backstopped by external borrowing.

- Missed opportunity in remittances – Remittances have surged to above 20% of GDP in recent years; however, 80% is used for consumption, with just 7% going into savings and 4% into business investments.

The result is a development model that leans on debt to bridge nearly every structural gap, from energy, infrastructure, climate resilience, basic services, and leaves little room to manoeuvre when conditions tighten.

From High‑Risk To High‑Intent Fiscal Strategy

Turning this vision into reality will require deliberate, sequenced policy choices over the next three to five years.

Illustrative Reform Levers And Potential Fiscal Payoffs

| Reform lever | Indicative potential impact (% of GDP, where stated) | Channel of relief |

|---|---|---|

| Reduce tax incentives and exemptions | Up to 4% to 5% (foregone revenue) | Higher domestic revenue, less need to borrow |

| Scale up e‑registration, e‑filing, e‑pay | Around 1% to 2% (typical low‑income gains) | Better compliance and collection |

| Improve spending efficiency (big sectors) | Up to about 4.9 in potential savings | More space for priority, growth‑enhancing outlays |

| Rationalise SOE transfers and guarantees | Several points of GDP in reduced support over time | Lower fiscal risks, fewer surprise bailouts |

| Deploy climate‑resilient debt instruments | Country‑specific, but can smooth shocks and amortisation | Lower crisis borrowing after disasters |

The government has begun taking necessary steps in this direction, including adopting a revised policy for waiving duties, preparing domestic revenue mobilisation strategies and updating debt transparency frameworks.

However, the challenge is sustaining the execution, particularly politically sensitive reforms such as SOE restructuring, subsidy targeting, and the stricter vetting of new loans against growth and climate priorities.

Path Forward – Safeguarding Growth, Rebalancing Risk

The Gambia's next chapter will be written in the space between its debt limits and its development ambitions.

Keeping borrowing below growth-damaging levels, while scaling investments in people, climate resilience and productive sectors, will require a tighter, more transparent fiscal social contract.

That means raising domestic revenues, spending habits, curbing SOE-related losses and deploying climate-smart financing tools so that, over time, public debt shifts from Achilles heel to stabilising anchor for a fairer, more resilient economy.