Africa's clean energy transition is often framed as inevitable. It is framed as negotiable. New evidence shows that without justice, equity, and political realism, the continent's transition risks deepening poverty rather than reducing emissions.

This is not an argument against renewables. It is an argument for sequencing, inclusion, and policy honesty, recognising Africa's energy poverty, development needs, and fragile social contracts before imposing transition pathways designed elsewhere.

Transition Without Justice Is Not Progress

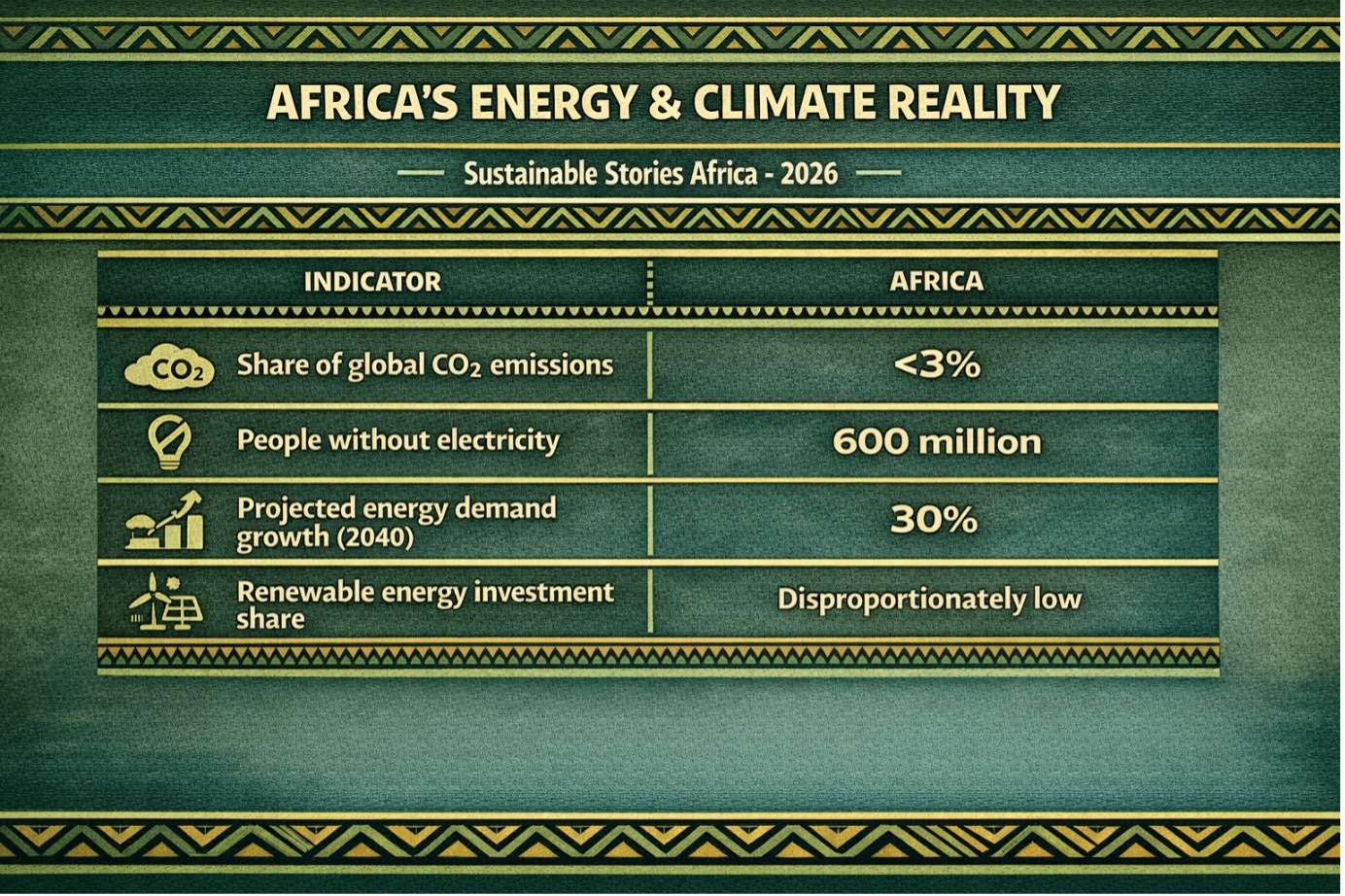

Africa sits at the centre of a global contradiction. The continent contributes less than 3% of historical greenhouse-gas emissions; however, it faces some of the world's most severe climate impacts.

At the same time, it holds vast reserves of fossil fuels and critical minerals essential to the global clean-energy transition. This dual reality places Africa under pressure to decarbonise while still struggling to electrify.

A growing body of research now warns that this tension cannot be resolved through only technology. A detailed policy and justice review on Africa's clean energy transition argues that without fairness, inclusion, and context-specific policy design, "clean" energy risks becoming socially disruptive rather than transformative.

The report's central message is clear: Africa's transition must be incremental, pragmatic, and just. Energy security, affordable access, and economic development are not obstacles to climate action; they are prerequisites for its legitimacy.

Africa's Energy Crisis Is Structural

Africa's energy challenge is not a future risk; it is a present emergency. Almost 600 million Africans still lack access to electricity, while many who are connected face an unreliable, expensive supply.

In several countries, electricity access remains below 20%, even as populations grow and urbanise rapidly.

Energy demand in Africa is projected to rise by nearly 30% by 2040, far outpacing global averages.

However, the continent's share of global renewable-energy investment remains disproportionately low. This mismatch between rising demand and constrained supply defines Africa's transition dilemma.

The study argues that forcing a rapid fossil-fuel exit without addressing access, affordability, and reliability risks continues to entrench inequality.

Energy poverty is itself a form of injustice, one that climate policy cannot afford to ignore.

Why Imported Transitions Don't Translate

Much of today's clean-energy discourse is shaped by Global North experiences, where energy systems are mature, grids are stable, and social safety nets cushion many forms of disruption. Africa's reality is fundamentally different.

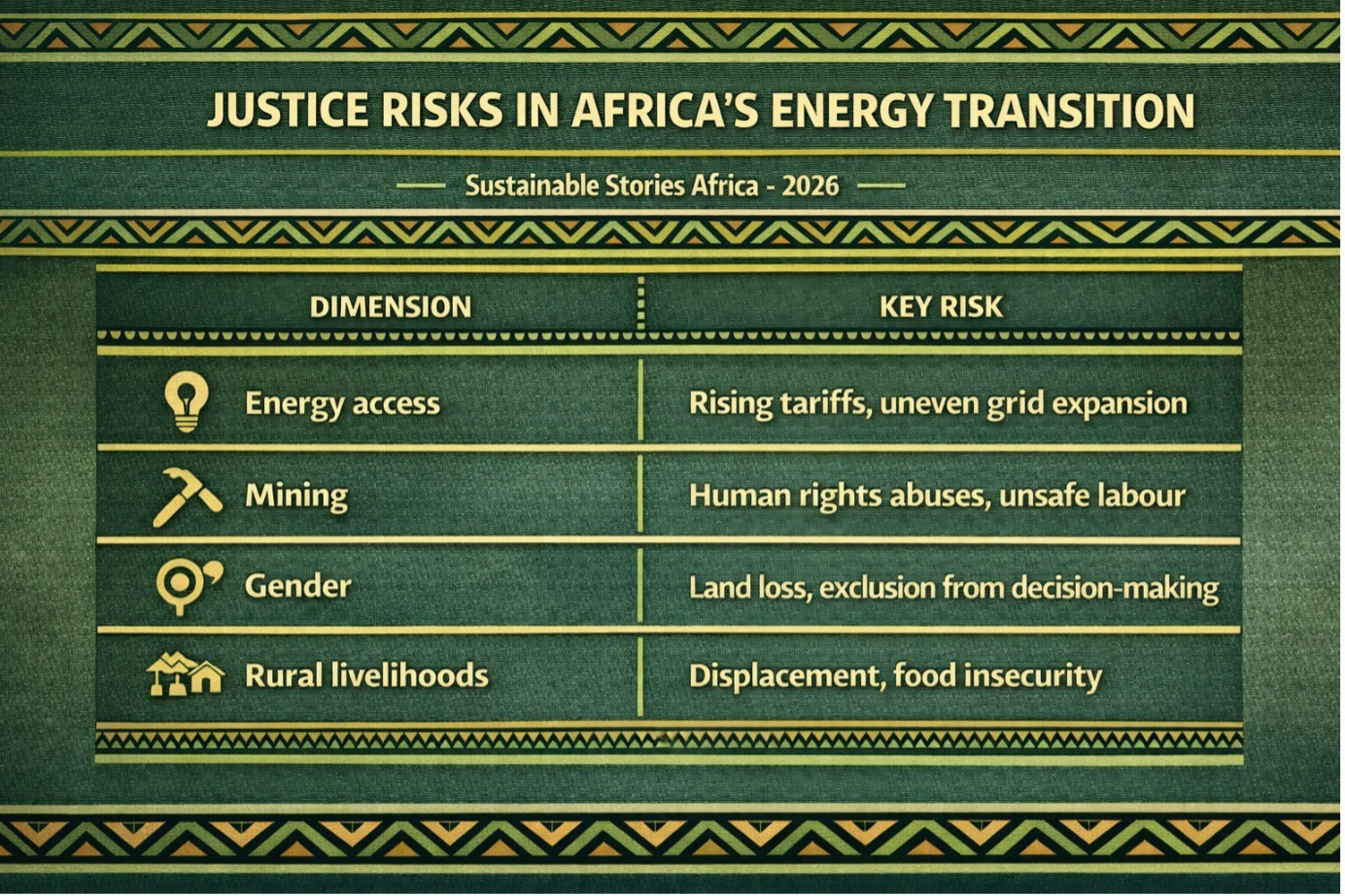

The research highlights how energy justice should consider who bears the costs and who captures the benefits of transition. Rural communities, indigenous groups, and low-income households are often excluded from decision-making, yet disproportionately affected by land acquisition, mining activity, or rising energy tariffs linked to "clean" projects.

Cultural and socio-economic dynamics further complicate transition pathways. In many African contexts, traditional fuels such as firewood and charcoal remain dominant not by choice, but by necessity—because they are accessible and affordable. Clean alternatives that ignore these realities risk rejection, not adoption.

Africa's Energy & Climate Reality

| Indicator | Africa |

|---|---|

| Share of global CO₂ emissions | <3% |

| People without electricity | 600 million |

| Projected energy demand growth (2040) | 30% |

| Renewable energy investment share | Disproportionately low |

Justice Makes Transition Economically Viable

A just energy transition is not a moral add-on. It is an economic strategy. The report makes a compelling case that inclusive energy systems can simultaneously advance poverty reduction, job creation, and climate resilience.

Renewable energy, when deployed thoughtfully, can expand access through mini-grids, support agricultural productivity through solar irrigation systems, and lead to a reduction of household health burdens linked to indoor air pollution.

Evidence cited in the study shows that a 1% increase in renewable-energy consumption could lift Africa's long-term economic growth by nearly 2%.

Crucially, justice also applies upstream. Over 70% of global cobalt supply comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo, with a significant share mined under hazardous conditions, including child labour. A transition that cleans grids while exploiting miners is neither ethical nor sustainable.

Gender equity emerges as another fault line. Women provide up to 80% of agricultural labour in parts of Africa, yet frequently lose land or decision-making power when energy projects expand. Ignoring this reality risks turning clean energy into a driver of food insecurity rather than resilience.

Justice Risks in Africa's Energy Transition

| Dimension | Key Risk |

|---|---|

| Energy access | Rising tariffs, uneven grid expansion |

| Mining | Human rights abuses, unsafe labour |

| Gender | Land loss, exclusion from decision-making |

| Rural livelihoods | Displacement, food insecurity |

Policy Must Sequence, Not Shock

The study rejects "one-speed" transition models. Instead, it calls for incremental, low-carbon development pathways that balance climate goals with economic realities.

This includes continued, time-bound use of oil and gas where necessary to fund development, while accelerating renewable energy where they deliver immediate social value.

Evidence-based policymaking is central. Governments are urged to integrate justice assessments into energy planning, examining the distributional impacts of projects as they are approved.

Gender-inclusive governance, community consultation, and human-rights safeguards in mineral supply chains are presented not as optional extras, but as core policy requirements.

The Russia–Ukraine energy shock is cited as a cautionary tale: even advanced economies revert to coal when security is threatened. Africa, with weaker safety nets, cannot afford abrupt transitions that compromise reliability or affordability.

PATH FORWARD – Justice Is Africa's Transition Anchor

Africa's clean-energy transition will succeed only if it is just, inclusive, and grounded in lived realities.

Energy access, affordability, and economic growth must advance alongside decarbonisation, not after it.

The path forward lies in pragmatic sequencing: scaling renewables where they reduce poverty today, protecting vulnerable groups, and aligning climate ambition with development justice.