Across the global South, agriculture rests on healthy forests, soils, water and wildlife. However, it is steadily degrading the very biodiversity that underpins food security.

From Latin America to Africa and Asia, land clearing, chemical-intensive farming and poor water management are pushing ecosystems toward dangerous tipping points, weakening the natural systems that stabilise yields and rural livelihoods.

A report on Agriculture Rooted in Biodiversity reframes nature as core infrastructure, not a policy afterthought. The message is stark: unless agricultural policy, finance and extension systems pivot decisively toward nature-positive practices, productivity, incomes and climate resilience will erode together.

Agriculture's Biodiversity Blind Spot

Agriculture now drives nearly 75% of negative impacts on land-based biodiversity, even as it relies on healthy ecosystems for pollination, water regulation, soil formation and climate stability.

According to the report Agriculture Rooted in Biodiversity, between 2001 and 2022, most global deforestation has stemmed from conversion to crops and cattle, with losses concentrated in Latin America, Africa and Asia-Pacific. Consumption in high‑income countries displaces a large share of this damage through imports and exporting biodiversity loss to the Global South.

However, more than 50% of the critical natural assets that underpin agriculture, such as forests, wetlands and other ecosystems providing irreplaceable services, remain largely intact, while a further share is degraded but still restorable.

The choices governments, financiers and agribusinesses make over the next few decades will determine whether these landscapes continue to buffer food systems, or tip into collapse.

Food Systems on Fragile Ground

Agriculture is simultaneously a victim and primary driver of biodiversity loss. It accounts for around 75% of adverse impacts on terrestrial biodiversity, threatens up to 85% of species at risk of extinction, and has contributed to a steep decline in monitored wildlife populations since 1970.

Deforestation illustrates the feedback loop. Large‑scale commodity agriculture dominates forest conversion in the Brazilian Amazon and Indonesia, while in Africa smallholder expansion is the leading cause of forest loss.

However, only about 50% of cleared land ends up in productive agriculture; the rest is tied up in speculation, short‑lived cultivation, fires and tenure disputes, magnifying nature loss without durable food gains.

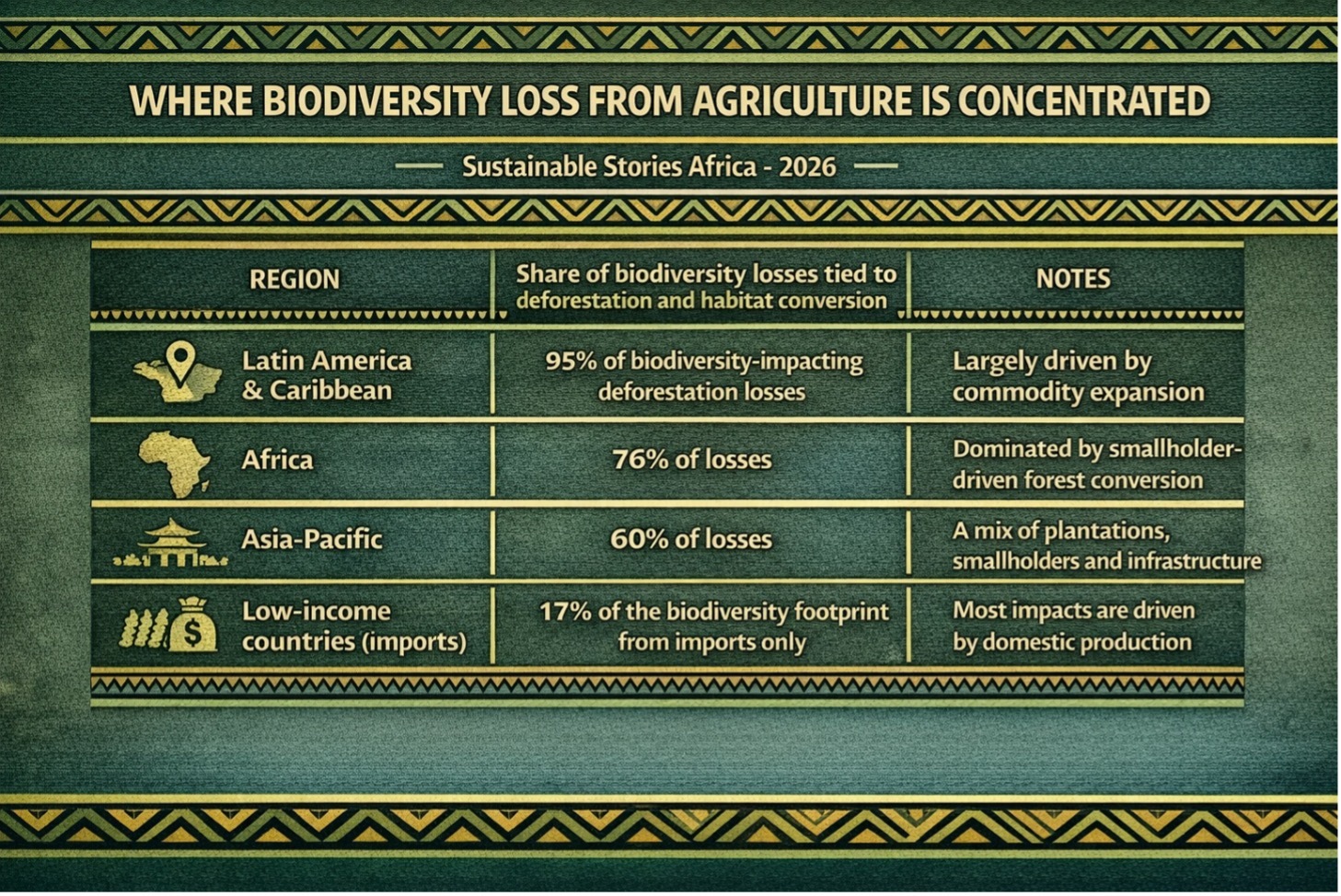

Where Biodiversity Loss From Agriculture Is Concentrated

| Region | Share of biodiversity losses tied to deforestation and habitat conversion | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Latin America & Caribbean | 95% of biodiversity-impacting deforestation losses | Largely driven by commodity expansion |

| Africa | 76% of losses | Dominated by smallholder-driven forest conversion |

| Asia-Pacific | 60% of losses | A mix of plantations, smallholders and infrastructure |

| Low-income countries (imports) | 17% of the biodiversity footprint from imports only | Most impacts are driven by domestic production |

When natural areas cross ecological tipping points, the consequences cascade far beyond forest edges.

How Agriculture Unravels Nature's Safety Net

The report highlights four main channels through which prevailing agricultural models degrade biodiversity and the ecosystem services that support food production: land and soil management, water use, pollution and genetic erosion. These pressures interact, creating compound risks to yields and livelihoods.

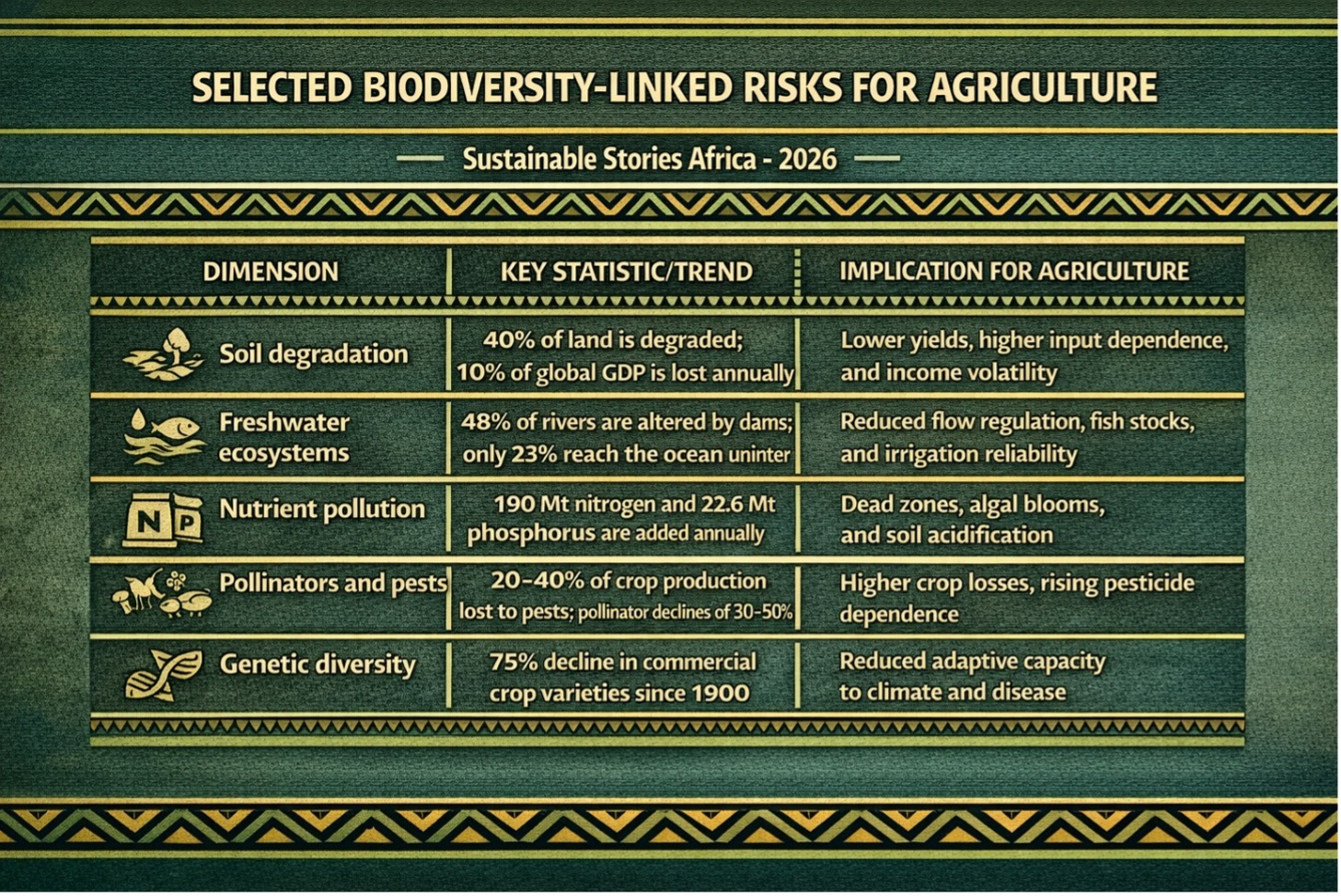

Modern monocropping, intensive tillage and overgrazing drive soil degradation on up to 40% of the world's land, with nearly 100 million hectares degrading further every year.

Degraded soils store less carbon, support fewer organisms, and deliver yields that can be 15% - 30% lower than under healthy conditions.

Selected Biodiversity-Linked Risks for Agriculture

| Dimension | Key statistic/trend | Implication for agriculture |

|---|---|---|

| Soil degradation | 40% of land is degraded; 10% of global GDP is lost annually | Lower yields, higher input dependence, and income volatility |

| Freshwater ecosystems | 48% of rivers are altered by dams; only 23% reach the ocean uninterrupted | Reduced flow regulation, fish stocks, and irrigation reliability |

| Nutrient pollution | 190 Mt nitrogen and 22.6 Mt phosphorus are added annually, exceeding safe limits | Dead zones, algal blooms, and soil acidification |

| Pollinators and pests | 20–40% of crop production lost to pests; pollinator declines of 30% - 50% | Higher crop losses, rising pesticide dependence |

| Genetic diversity | 75% decline in commercial crop varieties since 1900 | Reduced adaptive capacity to climate and disease |

Water management is equally destabilising. Agriculture accounts 70% use of freshwater withdrawals and 85% - 90% of consumptive use. Over‑abstraction and inefficient irrigation exacerbate waterlogging, salinisation and wetland loss, while dams fragment rivers and degrade downstream ecosystems that regulate floods, store carbon and support fisheries.

Pollution compounds these pressures. Human activity now adds nitrogen and phosphorus to more than three times safe planetary limits, with agriculture responsible for over 90% of phosphorus pollution.

Fertiliser runoff and livestock waste are responsible for algal blooms and dead zones, while the use of pesticides in low-income countries remains in soils and waterways, at a rate of 153% above approved limits.

From Vicious Cycles to Nature-Positive Yields

Against this backdrop, "Agriculture Rooted in Biodiversity" is a production strategy, not a slogan. The report identifies critical natural assets ecosystems, which are delivering essential services, and shows that restoring them is by far the cheapest way to protect yields and manage risk.

More than half of these assets, accounting for 4.8 billion hectares, remain intact and should be global priorities. Another 3.8 billion hectares are degraded but restorable, offering a major opportunity to rebuild ecosystem services and stabilise farm incomes locally.

At the landscape level, practices such as intercropping, agroforestry and reduced tillage have been identified as essential agricultural practices, restoring soils and water cycles while improving yields and profitability when supported.

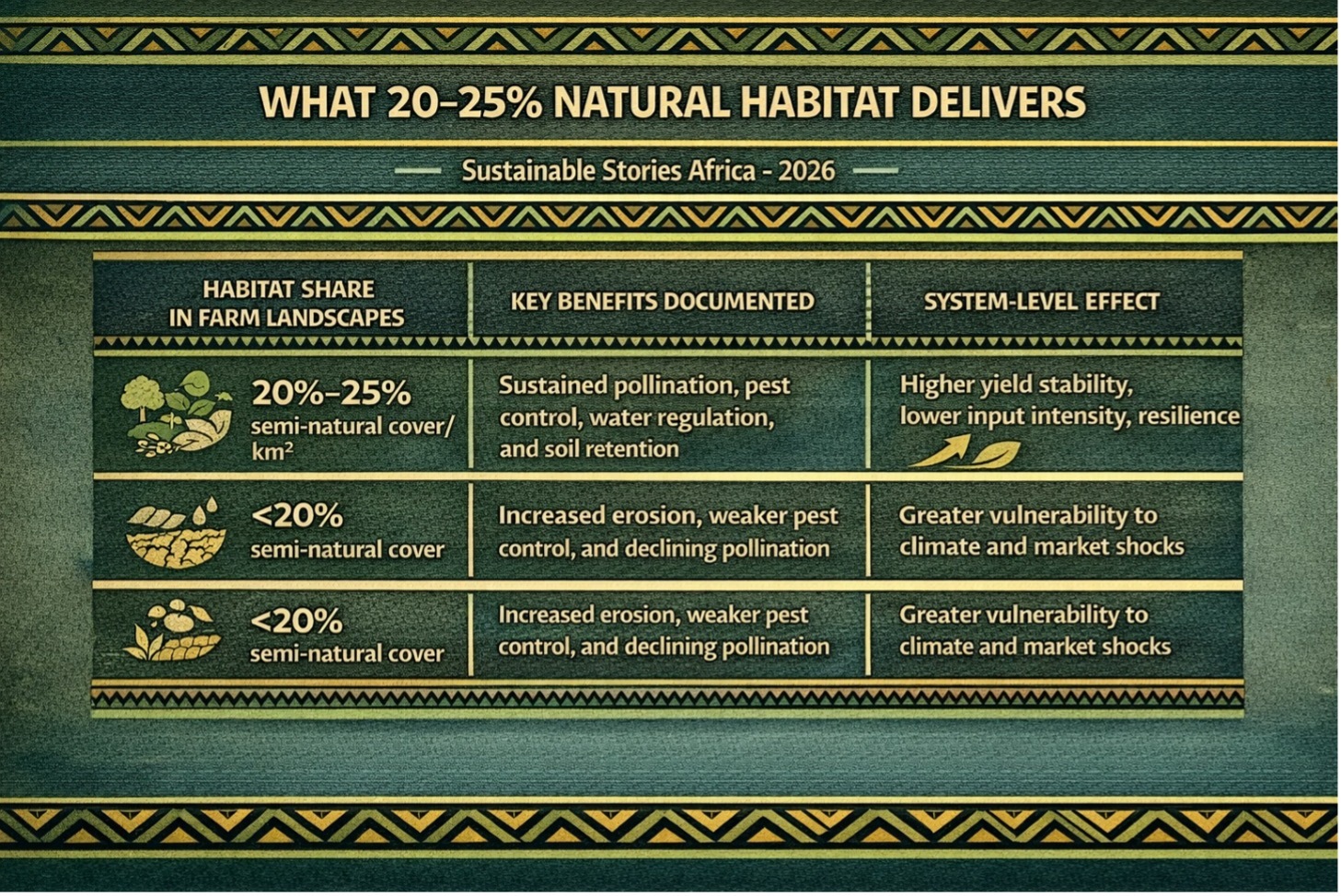

What 20–25% Natural Habitat Delivers

| Habitat share in farm landscapes | Key benefits documented | System-level effect |

|---|---|---|

| 20 - 25% semi‑natural cover/km² | Sustained pollination, pest control, water regulation, and soil retention | Higher yield stability, lower input intensity, resilience |

| <20% semi‑natural cover | Increased erosion, weaker pest control, and declining pollination | Greater vulnerability to climate and market shocks |

The economics reinforce the case. Investments in restoration and sustainable land management can return up to $30 for every dollar spent, once ecosystem services and avoided losses are counted. Redirecting $70 billion of harmful farm subsidies toward green innovation, thereby reducing food prices, increasing output, and releasing over 100 million hectares for restoration.

Repurposing Policy, Finance and Extension

The report distils these findings into three linked policy and investment packages: conserving and restoring natural land that underpins agriculture, scaling sustainable intensification, and financing transition through repurposed support, ecosystem payments and stronger monitoring.

On conservation, governments should use rapidly improving spatial data to prioritise intact and degraded critical natural assets. In stable areas, this means stronger protected areas, community governance, ensuring the management of fire outbreaks and invasive species; amidst looming threats, zoning, climate-smart planning and long-term restoration are required.

Sustainable intensification demands different tools. Nature-positive practices often require repeated hands-on extension, tailored inputs and patient finance before benefits emerge. The report urges long-horizon lighthouse programmes linking research, incentives, markets and farmer support.

Financing must shift, repurposing subsidies and rewarding ecosystem stewardship performance.

Path Forward – Biodiversity as Core Farm Infrastructure

The most important shift is conceptual. Biodiversity is not a side constraint to be managed after productivity and trade decisions, but a core infrastructure for food systems.

Planning, subsidies, credit and trade policy need to treat habitats, soil biota, genetic diversity and water cycles as assets on which agricultural competitiveness rests.

This demands re‑engineering agricultural support so that conserving critical natural assets, restoring degraded lands and embedding 20% – 25% semi‑natural habitat in production landscapes become baseline conditions for public finance.