The second half of the World Bank's 2025 World Development Report reads like a quiet manifesto for low‑ and middle‑income countries tired of importing other people's rules.

It argues that how countries choose, sequence and eventually write the standards that govern trade, technology, human capital, climate and public finance may matter as much as any loan or reform package in determining who climbs the development ladder and who stays stuck.

Rules now rival roads in shaping development

The second half of the report shifts from history to a hard question: how can governments turn standards from straitjackets into springboards for growth, inclusion and environmental resilience?

It anchors the answer in three moves along what it calls the "adapt–align–author" trajectory: first adjusting international standards to align with local realities, then aligning domestic rules with global norms as capacity rises, and ultimately creating new rules for adoption in areas such as digital payments and green taxonomies.

Underneath this is a blunt admission that most low‑ and middle‑income countries are still stuck in the first two stages. They face a paradoxical landscape in which technical non‑tariff measures now affect almost all of world trade; however, their national standards bodies sit on fewer than a third of ISO and IEC technical committees and depend heavily on selling conformity‑assessment services to stay afloat.

In practice, that makes it harder to challenge standards that don't fit their development needs, and easier to lock in low‑quality, high‑cost compliance traps at home.

When standards become make‑or‑break for markets

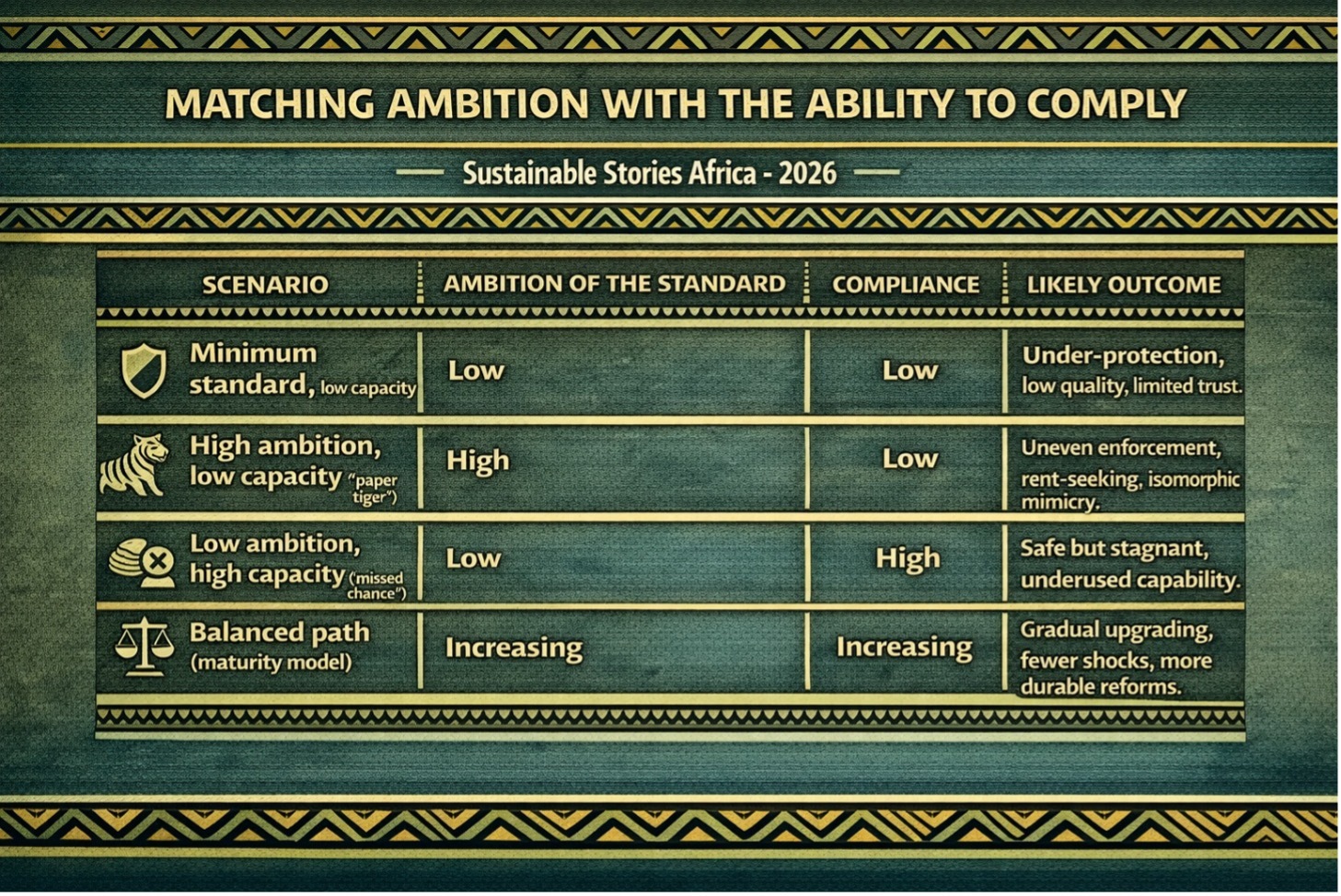

Too low, too high, or just right? The report crystallises the central policy tension in a simple 2‑by‑2 framework: ambition of standards versus capacity to comply. Set standards too low and countries under‑deliver on food safety, building norms, health quality or labour protection; set them too high relative to laboratories, inspectors and firm capabilities, and they create de facto bans, price spikes and fertile ground for uneven enforcement and corruption.

Technical non‑tariff measures now cover nearly 90% of world trade, with developing countries facing far more technical regulations than richer economies, based on their export structures.

The report identifies examples where stringent dairy or food rules in importing markets effectively price smallholders out of global supply chains, while ambitious and weakly enforced home‑grown environmental regulations leave both citizens and investors unsure which rules to align with.

Matching ambition with the ability to comply

| Scenario | Ambition of the standard | Compliance capacity | Likely outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum standard, low capacity | Low | Low | Under‑protection, low quality, limited trust. |

| High ambition, low capacity ("paper tiger") | High | Low | Uneven enforcement, rent‑seeking, isomorphic mimicry. |

| Low ambition, high capacity ("missed chance") | Low | High | Safe but stagnant, underused capability. |

| Balanced path (maturity model) | Increasing | Increasing | Gradual upgrading, fewer shocks, more durable reforms. |

The guidance is clear: in most low‑income contexts, capacity is the binding constraint. The priority is to build compliance systems, from labs to inspectors, while using standards that are ambitious enough to protect citizens but not so tough that they drive activity underground.

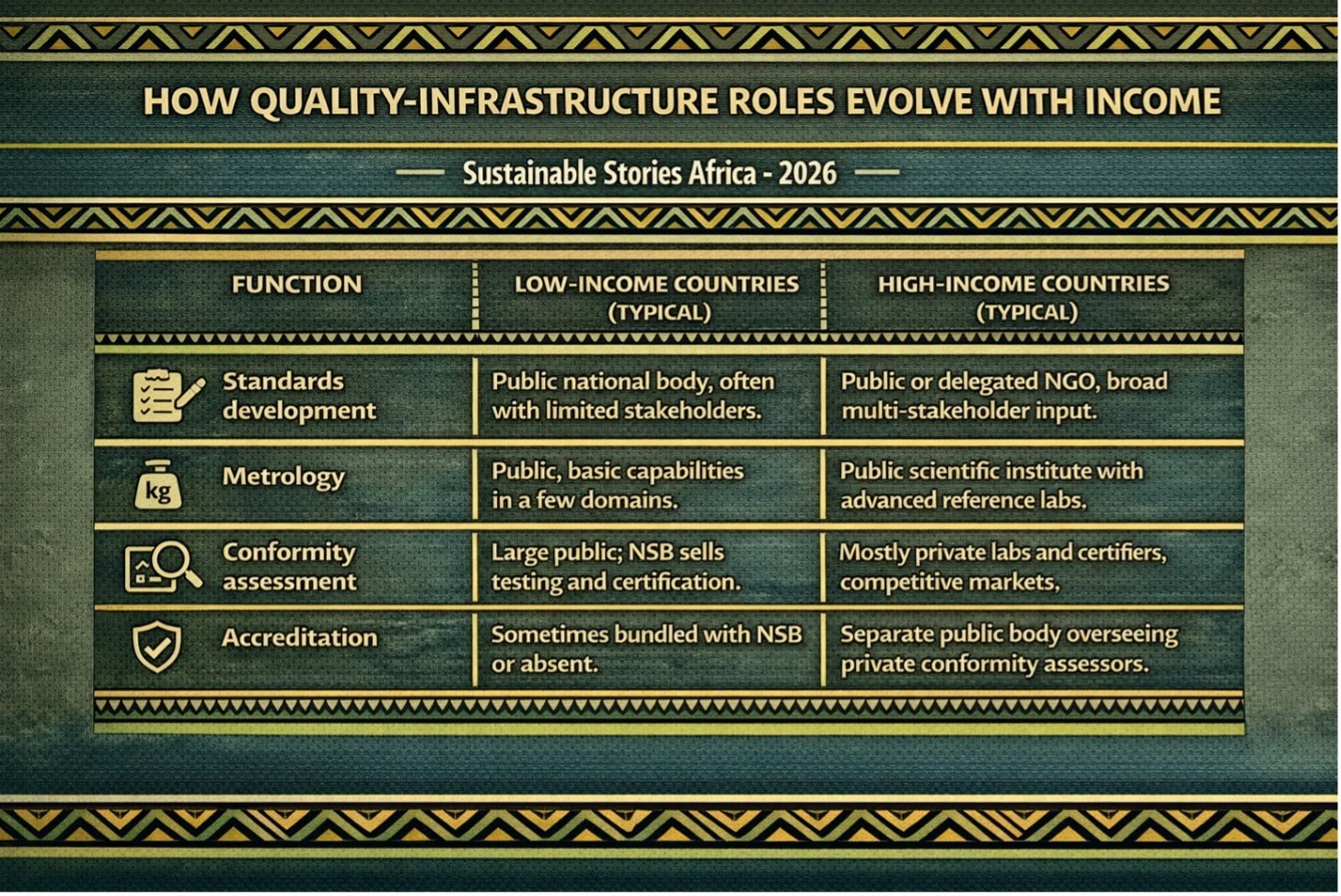

Inside the plumbing of quality and power

Who checks the checkers – and who pays? The report's most granular and revealing sections dissect the world's "quality infrastructure": the web of metrology institutes, standards bodies, accreditation agencies, labs and certification firms that turn paper rules into real‑world assurance.

In richer countries, these functions are typically separated, with private labs carrying out most of the testing and governments acting as referees. In poorer economies, national standards bodies often combine standard‑setting, testing, inspection and even accreditation under one roof.

That consolidation is partly about scarce resources, but it also creates textbook conflicts of interest. A World Bank–ISO survey of 116 national standards bodies reveals that in lower‑middle‑income economies, conformity‑assessment services account for nearly 40% of their revenue, compared with under 20% on average, and 75% of such bodies are also involved in drafting mandatory technical regulations.

When the same institution writes the rules and sells certificates against them, there is a built‑in incentive to multiply standards and keep them complex, even if firms struggle to comply.

How quality‑infrastructure roles evolve with income

| Function | Low‑income countries (typical) | High‑income countries (typical) |

|---|---|---|

| Standards development | Public national body, often with limited stakeholders. | Public or delegated NGO, broad multi‑stakeholder input. |

| Metrology | Public, basic capabilities in a few domains. | Public scientific institute with advanced reference labs. |

| Conformity assessment | Large public; NSB sells testing and certification. | Mostly private labs and certifiers, competitive markets. |

| Accreditation | Sometimes bundled with NSB or absent. | Separate public body overseeing private conformity assessors. |

The report argues for a "basics–broaden–balance" pathway: start by building core metrology and a small number of high‑stakes standards (for medicines, construction, food); broaden coverage and allow more private labs as demand rises; then rebalance so government focuses on oversight and market surveillance rather than being the main vendor of certificates.

Using standards to bend trade, tech and climate rules your way

From standard takers to standard authors

The report's second half is at its most hopeful, where it captures countries moving from passive adoption to actively shaping standards that reflect their strengths.

Ethiopia, for example, is co‑authoring international benchmarks for teff production while adapting others, using its indigenous grain to influence trade terms rather than accept them from abroad.

India, meanwhile, is advancing low‑voltage electrification norms and promoting a "digital public infrastructure hourglass" model, tightening core protocols for identity and payments while keeping innovation layers open. Together, these cases signal a quiet shift: developing nations are starting to codify their own development logic.

On trade and investment, the report finds that aligning domestic norms with credible global benchmarks can open markets and attract FDI, if pursued strategically. Lower‑income firms often see larger returns from voluntary standards but struggle with certification costs. Policy tools such as targeted subsidies, supplier‑development programmes, and FDI‑led diffusion down value chains can close that gap.

In climate governance, tiered emission standards, pioneered in China, India, and the EU, offer a pragmatic path for latecomers to leapfrog without derailing jobs or affordability.

Sequencing reforms where returns and risks are highest.

- Prioritise high‑stakes domains (health, buildings, food, pollution) for early strengthening of mandatory standards and enforcement.

- In finance, adopt proportionate Basel and FATF applications to avoid de‑risking SMEs and low‑income clients while still protecting stability.

- In digital, back open, interoperable core standards to avoid vendor lock‑in and align with regional initiatives.

- In trade, support exporters with pooled testing facilities and targeted certification support for key value chains.

Path Forward – Owning Standards, Sharing Power, Defending Policy Space

The report's final chapters argue that standard-setting has become a frontier of development politics. Low- and middle-income countries, though most affected by emerging rules on climate, technology, and finance, hold too few seats where these standards are shaped.

It calls for stronger representation through funded delegations, national standardisation strategies, and career pathways linking policy, industry, and law. For African and Southern policymakers, disengagement is no longer viable; the task now is to co‑author and adapt standards that anchor fair, livable futures, turning global rulemaking from a source of constraint into one of shared influence and opportunity.

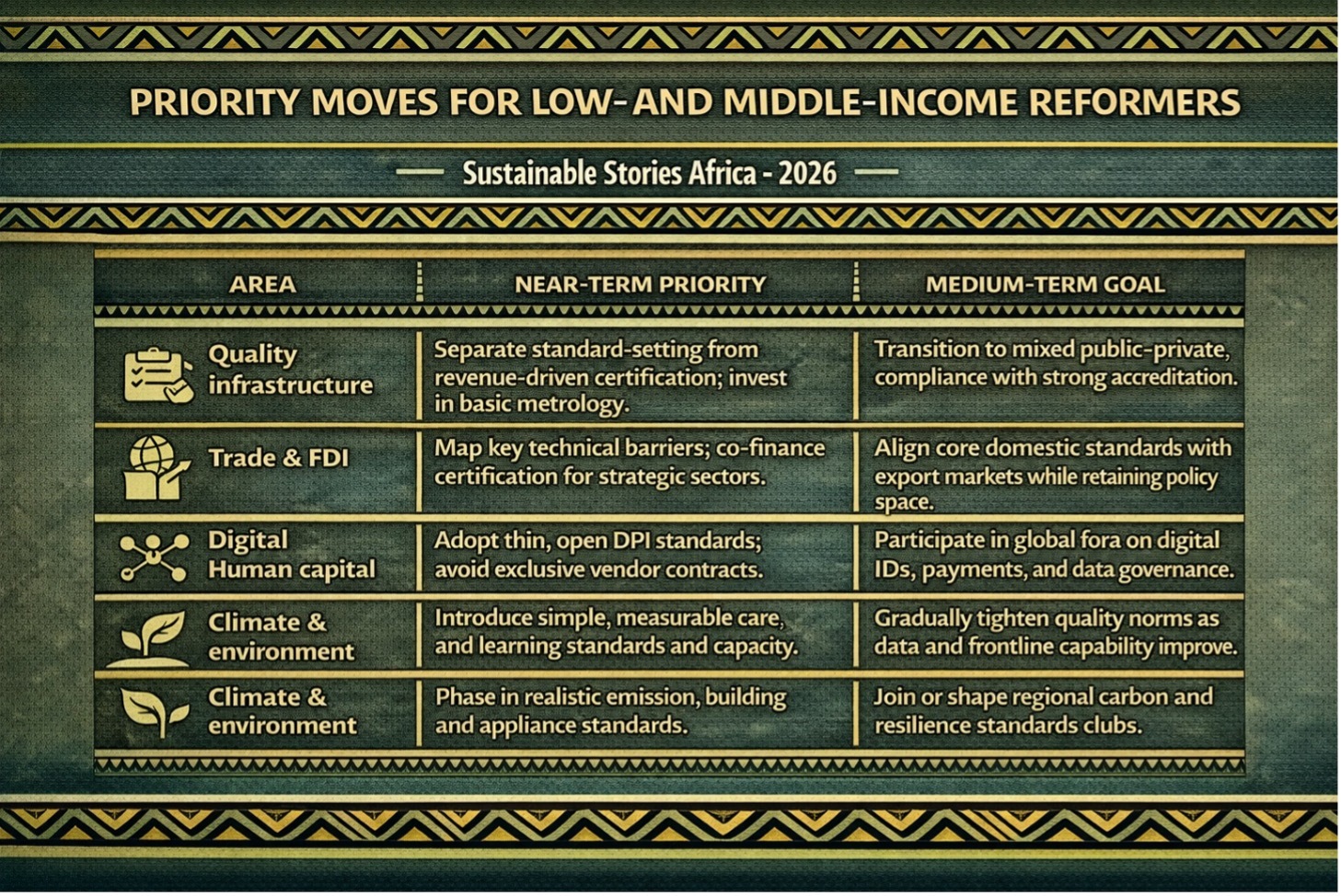

Priority moves for low‑ and middle‑income reformers

| Area | Near‑term priority | Medium‑term goal |

|---|---|---|

| Quality infrastructure | Separate standard‑setting from revenue‑driven certification; invest in basic metrology. | Transition to mixed public–private compliance with strong accreditation. |

| Trade & FDI | Map key technical barriers; co‑finance certification for strategic sectors. | Align core domestic standards with export markets while retaining policy space. |

| Digital | Adopt thin, open DPI standards; avoid exclusive vendor contracts. | Participate in global fora on digital IDs, payments, and data governance. |

| Human capital | Introduce simple, measurable care and learning standards and capacity. | Gradually tighten quality norms as data and frontline capability improve. |

| Climate & environment | Phase in realistic emission, building and appliance standards. | Join or shape regional carbon and resilience standards clubs. |