Nigeria has done the hard macro work: unifying the naira, scrapping fuel subsidies and tightening monetary policy have stabilised markets and lifted growth, at least on paper. But for millions of Nigerians, especially the poorest, reform still feels like a distant conversation in Abuja as food prices soar and poverty deepens.

Unless the government moves quickly to bring "policy to people" through cheaper food, smarter public spending and scaled safety nets, the political patience underwriting these reforms may not last.

Reform Promises, Empty Pots

Nigeria is finally purportedly posting the kind of macro headline technocrats like. This is according to the World Bank's Nigeria Development Update report of October 2025. A growth of 4.1% in 2024, a projected 4.2% - 4.4% growth through 2027, a current account surplus above 6% of GDP, and foreign reserves currently above $41 billion.

The naira market has been largely unified, FX backlogs cleared, and inflation is beginning a fragile disinflation path, helped by an aggressive 875 basis point tightening since early 2024.

When Stabilisation Bypasses The Market Stall

However, these gains sit uneasily with a harsher reality on the streets. Average consumption per person reduced by 6.7% between 2019 and 2023, and the share of Nigerians living in poverty increased from 40% to 56%. An estimated 141 million people are expected to be poor by 2026, with ultra‑poverty doubling to 27%. In the Northeast, more than eight in ten people are estimated to be poor, and the poorest households are now spending almost 70% of their budgets on feeding alone.

Macro Wins, Market Stalls, Mounting Social Risk

The Nigeria Development Update is blunt: reforms have "stabilised the economy, but Nigerians, however, have yet to reap their benefits significantly."

Services and the non‑oil industry are major contributors to this perceived growth. ICT expanded 7% in the first half of 2025, finance by 15.6%, and construction picked up with state‑level capital projects. However, agriculture, which employs a third of the workforce, grew by only 1.5% and remains strangled by insecurity, weak logistics and climate shocks.

On prices, the story is even more stark. Sequential inflation is easing, but the cumulative price index for staple foods most consumed by poor households (rice, palm and groundnut oil, beans, bread, maize flour, yams, beef) rose 406% between 2016 and 2024, versus 201% for overall food and 161% for headline inflation. Food inflation has averaged 27% since 2021, far higher than its neighbours like Benin, Niger and Cameroon, making every policy misstep immediately visible on the plate.

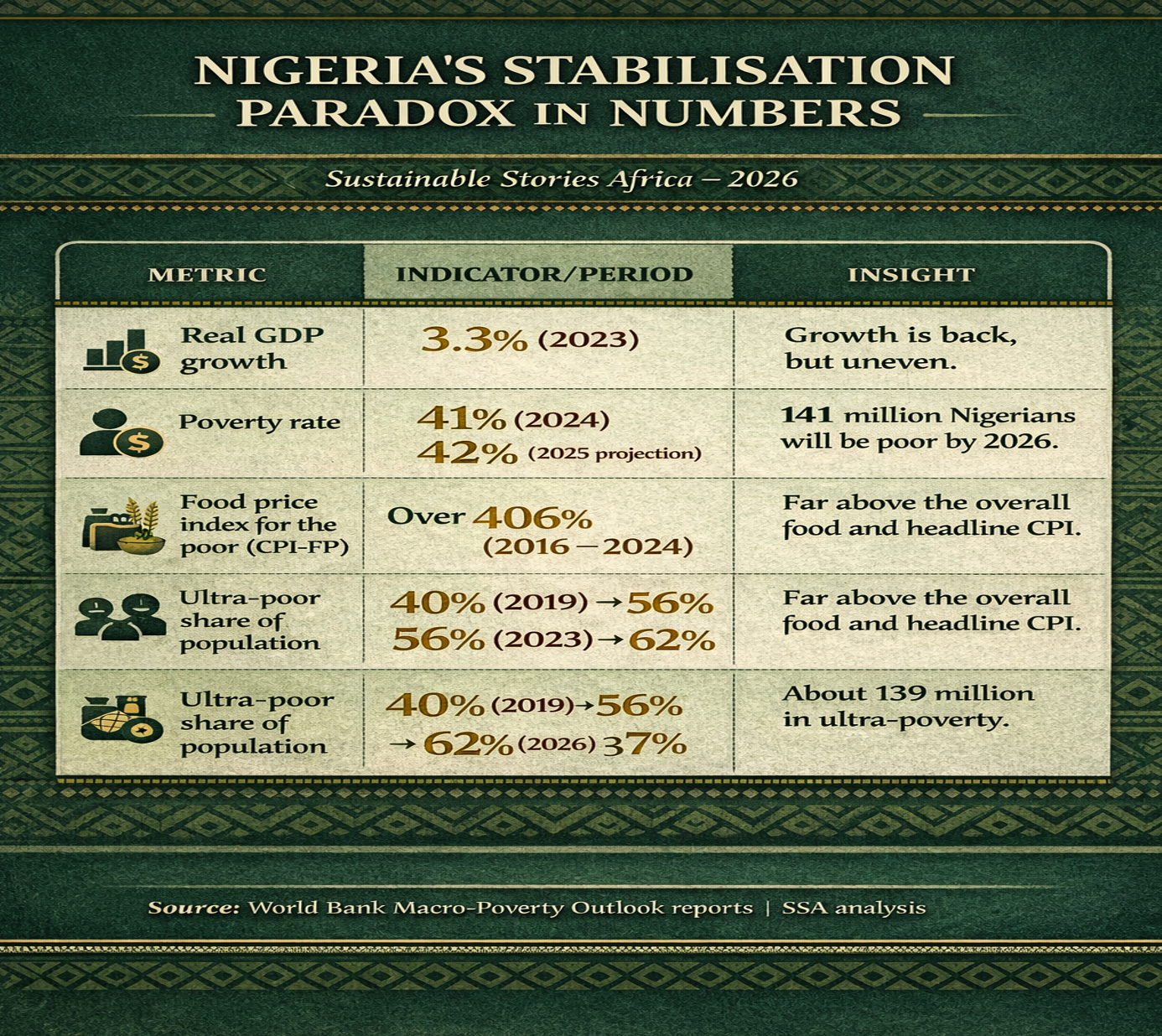

Nigeria's stabilisation paradox in numbers

Metric | Indicator/period | Insight |

|---|---|---|

Real GDP growth | 3.3% (2023), 4.1% (2024), 4.2% (2025 projection) | Growth is back, but uneven. |

Poverty rate | 40% (2019) → 56% (2023) → 62% (2026 projection) | 141 million Nigerians will be poor by 2026. |

Food price index for the poor (CPI‑FP) | Over 406% (2016–2024) | Far above the overall food and headline CPI. |

Ultra‑poor share of population | 14% (2019) → 27% (2023) | About 139 million in ultra‑poverty. |

Food, Federalism And The Geography Of Pain

Inflation Bites Hardest Where States Are Weakest. The report's most uncomfortable insight is that Nigeria's food crisis is largely policy‑made. Import bans or steep duties cover staples like rice, wheat products, sugar, tomatoes, beverages, and even key inputs such as fertilisers and cement, raising production costs for smallholders and processors while entrenching a handful of waiver‑holding firms that dominate imports. In rice, three companies with waivers account for 96% of imports; for wheat, three firms handle 86%; for sugar, a single company controls 82%.

Layer on poor roads, extortionate interstate checkpoints, negligible cold‑chain infrastructure and post‑harvest losses of 76% for tomatoes, 25% for maize and 34% for catfish, and it becomes clear why food inflation in the North, Nigeria's breadbasket and its poorest region, is running hottest.

Conflict and banditry in farm belts, combined with only 3% of land formally titled, further depress investment and keep yields in rice and maize below targets despite years of "self‑sufficiency" rhetoric.

Why does food cost so much in Nigeria

Driver | Evidence | Distributional effect |

|---|---|---|

Trade barriers | Bans/duties on rice, wheat, sugar, tomatoes, and fertilisers. | Higher prices, narrow competition. |

Market concentration | 3 firms = 96% rice imports; 1 firm = 82% sugar. | Market power, rent‑seeking. |

Structural constraints | 76% tomato loss; 25% maize; 34% catfish. | Wasted output, higher consumer prices. |

Conflict & tenure | Rising farm conflicts: only 3% land is titled. | Lower investment, lower yields, greater poverty. |

Meanwhile, fiscal federalism is quietly shifting the balance of power. In 2024, states received for the first time more from FAAC distributable revenues (N5.3 trillion) than the Federal Government (N5.0 trillion), as statutory deductions, special state interventions and massive refunds to states and LGAs eroded the federal share. Yet despite this revenue windfall, many states have not meaningfully scaled funding for education, health or social protection, and local governments, which are formally responsible for primary schools and primary health care provision, remain under‑resourced and opaque.

From Macro Story To Market Trust

Cheaper Food, Visible Services, Credible Support

If Nigeria wants citizens to stick with painful reforms, three visible shifts are needed.

- First, food: easing import bans and aligning with ECOWAS and AfCFTA tariffs for key staples and inputs would quickly relieve pressure, especially if paired with a serious attack on domestic trading costs, such as interstate levies, unnecessary inspections, and port‑to‑farm logistics snarls. Farmers need cheaper fertiliser and seed, reliable roads and storage, and real‑time weather information, not just new slogans.

- Second, public money: presenting a consolidated national fiscal picture, placing principal repayments "below the line" and publishing timely, reconciled data for all three tiers of governance, would help markets see that the fiscal position has improved as revenues rose from 4.4% of GDP in 2021 to 8.4% in 2024. Reining in statutory deductions and oversized "costs of collection" for revenue agencies, and benchmarking them to peers like Kenya or Ghana, would free space for classrooms, clinics and rural roads without new taxes.

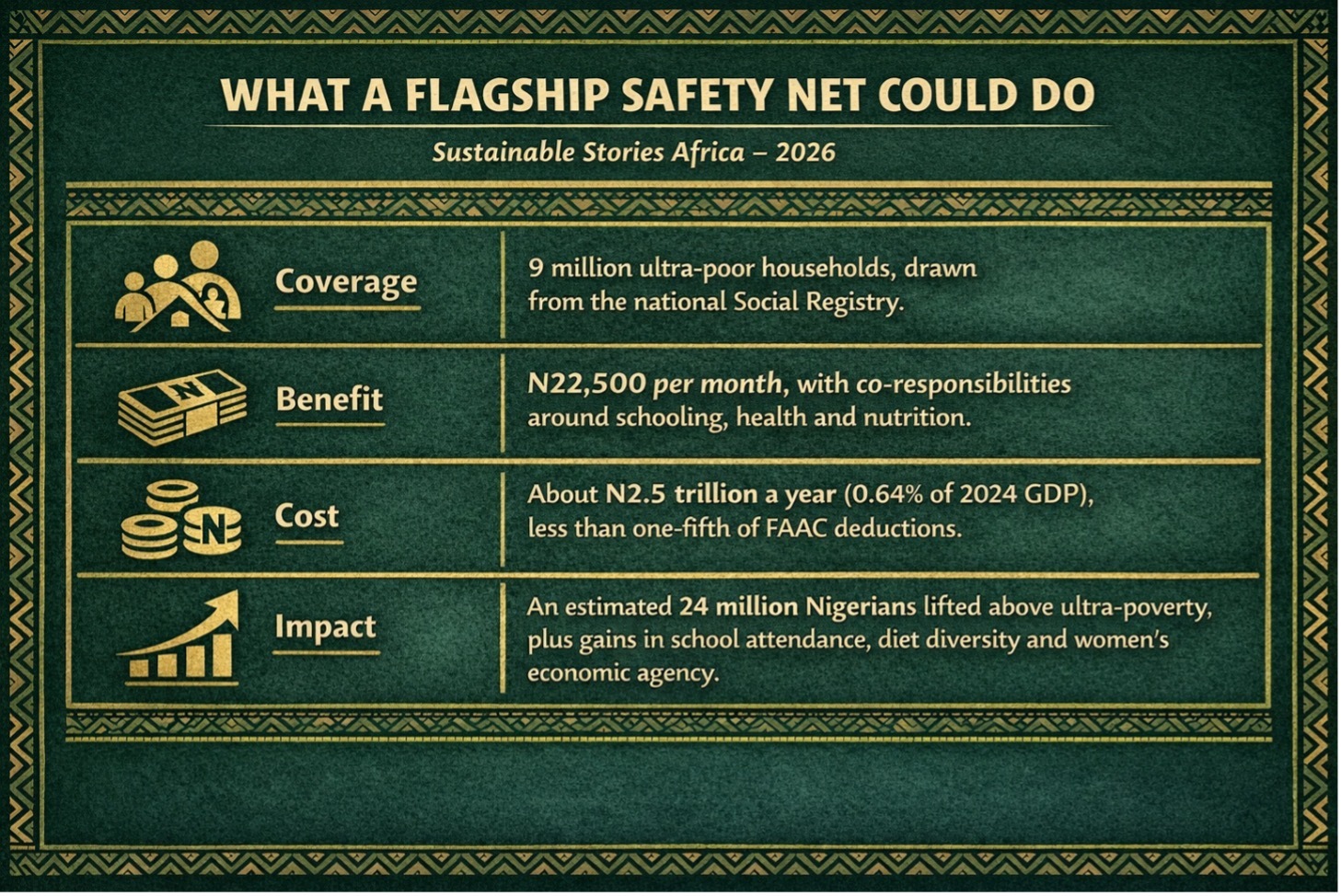

- Third, protection: Nigeria's social registry now covers some 86 million people across 19 million households, making it the largest database of poor and vulnerable households in Sub‑Saharan Africa. Used properly, it can move the country from ad‑hoc palliatives to predictable support. A basic safety‑net that pays N22,500 a month (around 20% of the ultra‑poverty line) to about 9 million ultra‑poor households would cost roughly 0.64% of GDP a year, around 19% of FAAC deductions in 2024, and could lift 24 million people out of ultra‑poverty.

Linking Abuja’s Savings To Household Survival

Delivering HOPE, Not Just Headlines, At Scale. Nigeria has already stress‑tested some of these ideas. The HOPE direct benefit program delivered three tranches of N25,000 to 15 million households, primarily used for food, and evaluations show beneficiaries reported higher perceived trust in government and improved welfare versus similar non‑recipients.

Layered pilots that combined cash with behavioural nudges and livelihoods packages, such as a N150,000 grant plus savings groups, coaching and skills training, have generated perceived gains in employment, micro‑enterprise profits, consumption and child outcomes that persisted beyond the project window.

The question now is less about design and more about political will. Will the savings from fuel subsidy removal and exchange‑rate unification be systematically channelled into rule‑based safety nets and targeted food‑supply reforms, or dissipate in opaque earmarked deductions, parastatal slush funds and short‑term state palliatives?

A renewed intergovernmental compact, using performance‑linked transfers and sector‑wide compacts in health, education and social protection, could align federal and state incentives around human capital and resilience rather than consumption of federal cash.

For a young, urbanising country where over half the population is already poor, the stakes are existential. If reforms continue to be experienced as something that stabilises markets but empties kitchens, political backlash is a matter of when, not if. If, instead, Nigeria can make every percentage point of disinflation and every extra naira of tax visible in fuller plates, better schools and reliable safety nets, "from policy to people" will read less like a slogan and more like a social contract.

Path Forward – Making Reform Gains Tangible, Fast

Turning Fiscal Space Into Food, Dignity, Opportunity

Over the next three years, Nigeria's reform credibility will hinge on whether macro discipline is matched by micro fairness: lower structural food prices, more honest and efficient use of public funds, and a truly national safety net that cushions shocks and builds human capital.

That means cutting the policy wedges that make Nigerian rice dearer than Beninois, publishing a consolidated fiscal dashboard in near‑real time, and locking in a baseline transfer for the ultra‑poor financed from Nigeria's own revenues, not donor whims.

If the government can show that FX unification, tax reform and subsidy removal are funding safer roads to farms, functioning clinics, and regular digital transfers to the poorest women, the politics of reform will look very different from the protests of the past decade.

Nigeria is closer than it has been in years to a virtuous cycle of growth, trust and inclusion. However, whether it gets there now depends less on spreadsheets and more on whether policy finally lands where it matters most: in people's daily lives.