The World Bank's 2025 World Development Report argues that standards – from how children are taught to how debts are counted and digital payments run – now quietly shape who wins and who is left behind in development.

However, the same rules that promise order, trust and innovation can also entrench power, exclude the poor and overload weak bureaucracies if countries copy them without adapting to local realities.

Order, trust and a quiet revolution in rules

From the first clay tablet complaint in ancient Mesopotamia to today's Basel banking rules and PISA tests, standards have been the hidden infrastructure behind markets, states and technology.

In this first part of our opinion piece STANDARDS for DEVELOPMENT, the 2025 World Development Report traces how three families of standards – measurement, quality and compatibility – have underpinned everything from long-distance trade and pyramid-building to steam power, mass production, the internet and today's digital public infrastructure.

This shift has always been political as it is technical. Revolutionary France's metric system was sold as a universal, rational tool to dismantle feudal privilege, but it only took root after decades of authoritarian enforcement and hybrid use alongside familiar local units.

The report warns that a similar tension runs through today's "global best practice" – whether in accounting, exams or e‑payments – as countries navigate trade‑offs between speed and inclusion, ambition and capacity, and openness and capture.

When standards become development's new fault line

Rules quietly reshaping who gets ahead. The report's core claim is blunt: in an era of climate risk, polycrisis and digital acceleration, standards have become frontline development tools, not technical afterthoughts.

In finance, IFRS norms, Basel capital rules and FATF anti-money-laundering standards now shape which banks access global markets, at what cost and on what terms, with proportionality often determining resilience or exclusion.

In human capital, the stakes are immediate. The World Bank estimates 60% of deaths in low- and middle-income countries stem from preventable conditions, showing how health and education standards, from clinics to classrooms, can drive reform, narrow gaps, or deepen inequality by design globally today.

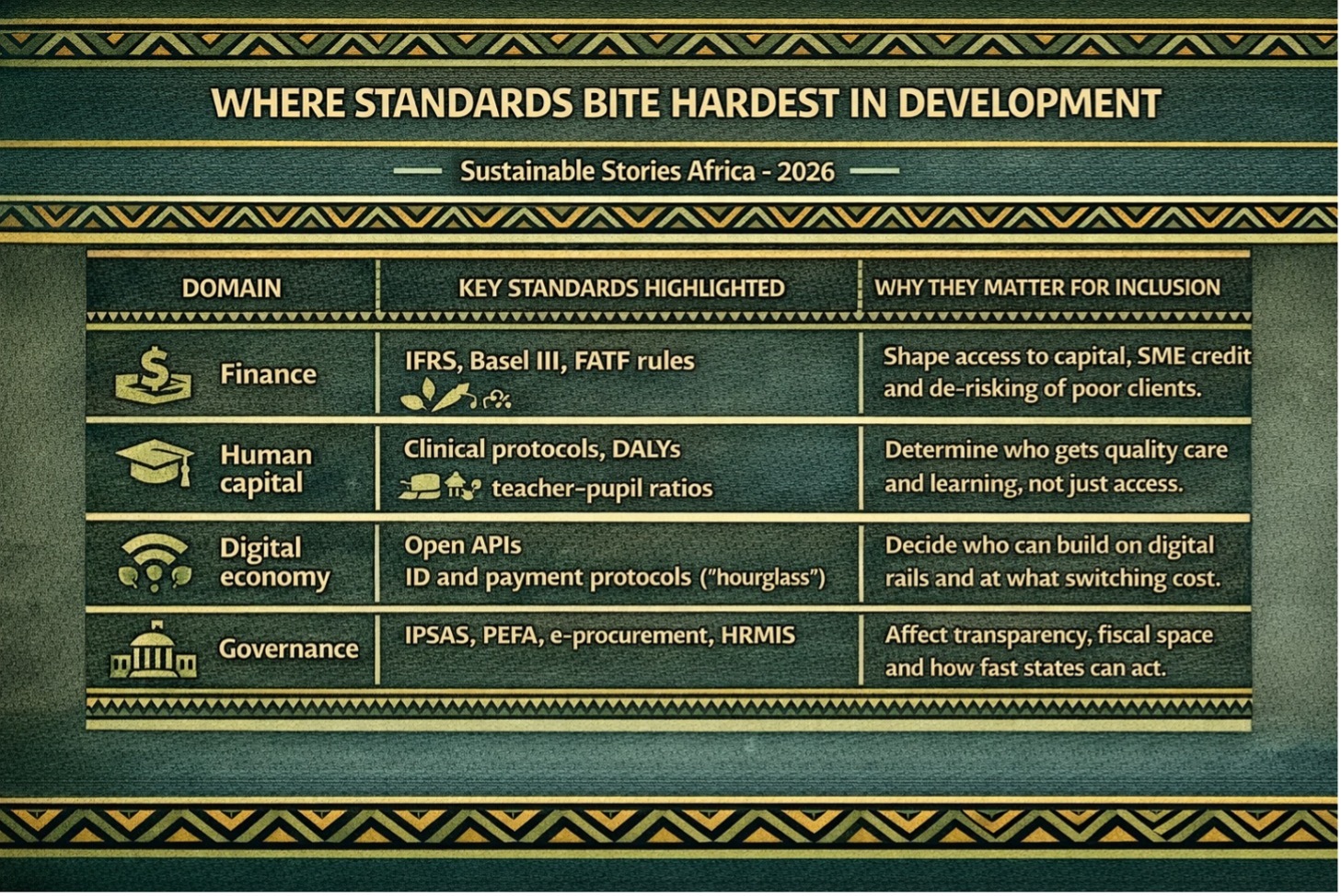

Where standards bite hardest in development

| Domain | Key standards highlighted | Why they matter for inclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Finance | IFRS, Basel III, FATF rules | Shape access to capital, SME credit and de‑risking of poor clients. |

| Human capital | Clinical protocols, DALYs, teacher–pupil ratios | Determine who gets quality care and learning, not just access. |

| Digital economy | Open APIs, ID and payment protocols ("hourglass") | Decide who can build on digital rails and at what switching cost. |

| Governance | IPSAS, PEFA, e‑procurement, HRMIS | Affect transparency, fiscal space and how fast states can act. |

How countries are bending global rules to local realities

Copying, stretching and rewriting global 'best practice'. The report highlights cases where countries began with modest, context-appropriate standards and raised the bar as capacity expanded, instead of importing OECD templates wholesale.

Viet Nam stands out: within a decade, it moved from below-average PISA scores to near or above OECD levels by tightening learning standards gradually, aligning assessments, investing in teachers, and closely tracking implementation costs.

Brazil's Ceará used simple literacy and numeracy benchmarks, transparent school data and municipal incentives to drive sharp gains.

In public finance, Viet Nam adapted IPSAS in phases, creating national standards that built capacity without overwhelming institutions with complex rules at once nationally.

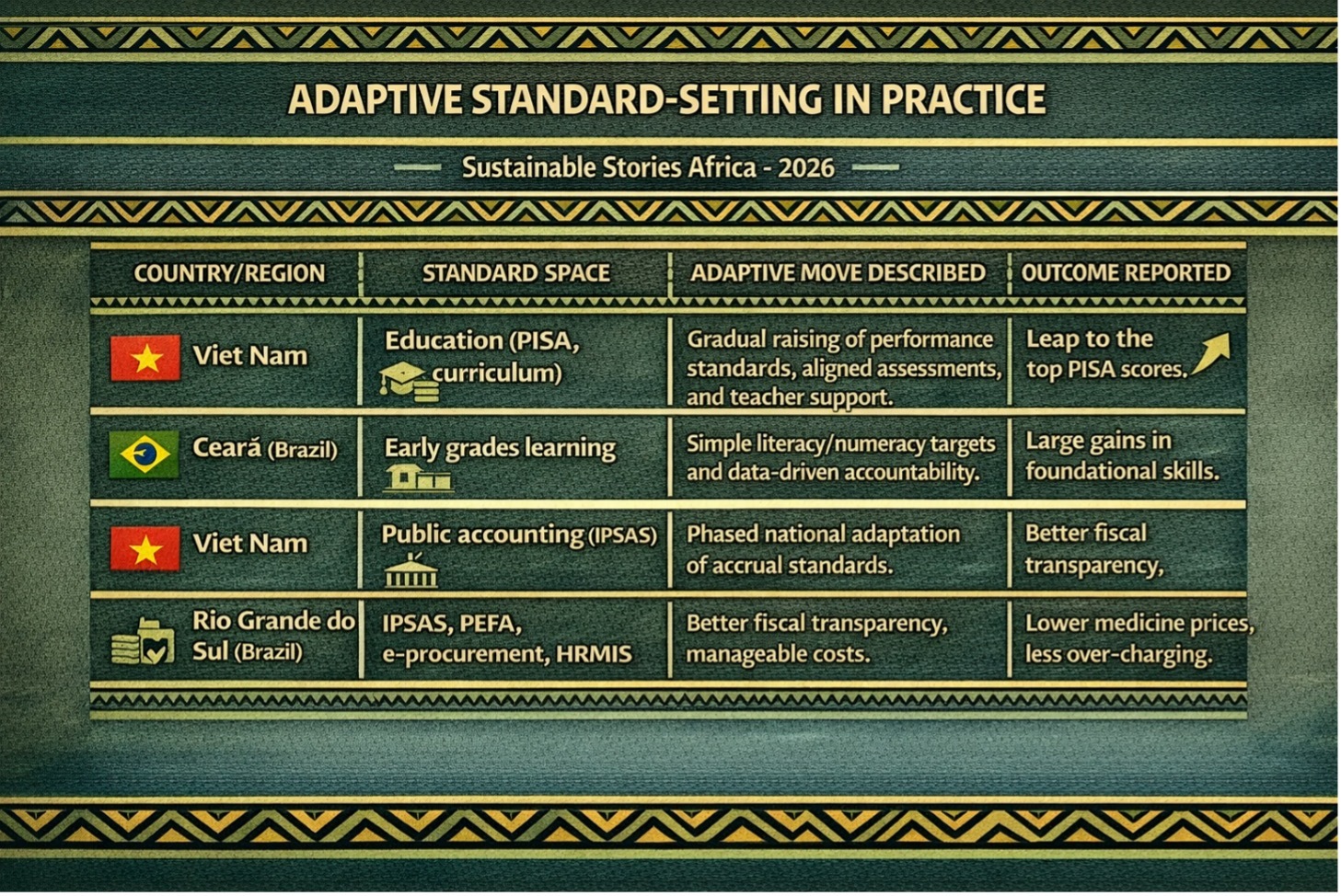

Adaptive standard‑setting in practice

| Country/region | Standard space | Adaptive move described | Outcome reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viet Nam | Education (PISA, curriculum) | Gradual raising of performance standards, aligned assessments, and teacher support. | Leap to the top PISA scores. |

| Ceará (Brazil) | Early grades learning | Simple literacy/numeracy targets and data‑driven accountability. | Large gains in foundational skills. |

| Viet Nam | Public accounting (IPSAS) | Phased national adaptation of accrual standards. | Better fiscal transparency, manageable costs. |

| Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil) | Procurement | Use of market‑based reference prices via e‑invoices. | Lower medicine prices, less over‑charging. |

From paperwork and paper tigers to living systems

Turning checklists into real capabilities. The report is unsparing on what it terms "paper tiger" governance: regimes where compliance multiplies but delivery stalls.

It documents cases where dense procedural standards in HR, procurement and budgeting absorb scarce administrative time, leaving officials in countries such as India waiting months for approvals before responding to urgent local needs.

The evidence instead points to a balance. Too few rules and too many rules both depress performance; a focused, well-chosen set improves outcomes.

Studies from Brazil, Ghana and Pakistan show that greater frontline discretion within clear standards, loosening rigid procurement thresholds while strengthening ex-post transparency, can cut costs, reduce delays and lift service quality.

In human capital, the same logic holds. Teaching at the Right Level succeeds by temporarily lowering expectations to match learning realities, then steadily raising standards as performance improves.

Five principles for 'standards‑smart' development

Choosing, sequencing and owning the rules that matter. The report's scattered recommendations cohere into a pragmatic five‑point playbook for governments and partners:

- Start from problems, not from templates – Rather than treating IPSAS, Basel or PISA as ends in themselves, governments should ask what failures – fiscal opacity, learning poverty, bank fragility – they are trying to solve and choose or adapt standards accordingly, including when "second‑best" but implementable rules beat pristine ones that will never be enforced.

- Cost the admin burden up front – A thousand‑page accounting code or complex HR regime demands scarce bureaucratic time; tools like PEFA can help measure the gap between standards on paper and practice, so reformers can phase changes and avoid overwhelming systems.

- Use data standards to unlock learning, not just compliance – The report highlights how e‑procurement, FMIS, HRMIS and open contracting taxonomies are spreading fast but often underused analytically; Brazil's medicine price reforms show what becomes possible when standardised data are turned into real‑time diagnostics rather than archived PDFs.

- Design digital rails around a thin, open 'waist' – In digital public infrastructure, the Bank backs the "hourglass" model: keep the core ID, payments and data‑exchange protocols as open, minimal and replaceable as possible to foster competition and prevent vendor lock‑in, while allowing more diversity and proprietary innovation at the edges.

- Institutionalise feedback and frontline agency – Civil service commissions, regulators and ministries should treat standards as living scaffolds, periodically revised with input from teachers, clinicians, procurement officers and local governments who experience them, rather than as fixed commandments from international handbooks.

Path Forward – Who writes the rules, and for whom?

Shared Rule-making for fair, livable futures. The report closes with a geopolitical provocation: the power to write, adopt and enforce standards remains concentrated in a few rich countries and industry blocs, even as climate stress, digitalisation and demography shift development's centre of gravity.

From ISO committees to Basel and FATF forums, lower-income countries are underrepresented while absorbing reforms designed elsewhere.

Rebalancing this landscape demands more than invitations. It requires investment in domestic standard-setting capacity, such as labs, curriculum bodies, health regulators, digital agencies, and coalitions that help countries move from standards takers to authors.

It also means acknowledging that standards encode values, risks and choices about uncertainty.

If there is one message for Africa and the wider South, it is this: adapt global standards selectively, shaping rules that fit realities.