Africa's food crisis is no longer driven by only conflict. An analysis by Oxfam highlights that water insecurity, shaped by climate change, is now the central force pushing millions into hunger across eastern and southern Africa.

When Water Fails, Food Follows

Hunger in Africa is increasingly shaped not by the absence of food, but by the absence of water. Across eastern and southern Africa, climate-driven disruptions to rainfall, rivers, and groundwater are undermining agriculture, livestock, and nutrition at a scale that humanitarian systems are struggling to match.

According to a 2025 Oxfam briefing paper, eight countries, which include Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Somalia, South Sudan, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, now sit at the epicentre of a deepening water-driven food emergency. These countries are simultaneously among the world's most water-insecure and are classified as hunger hotspots for 2025.

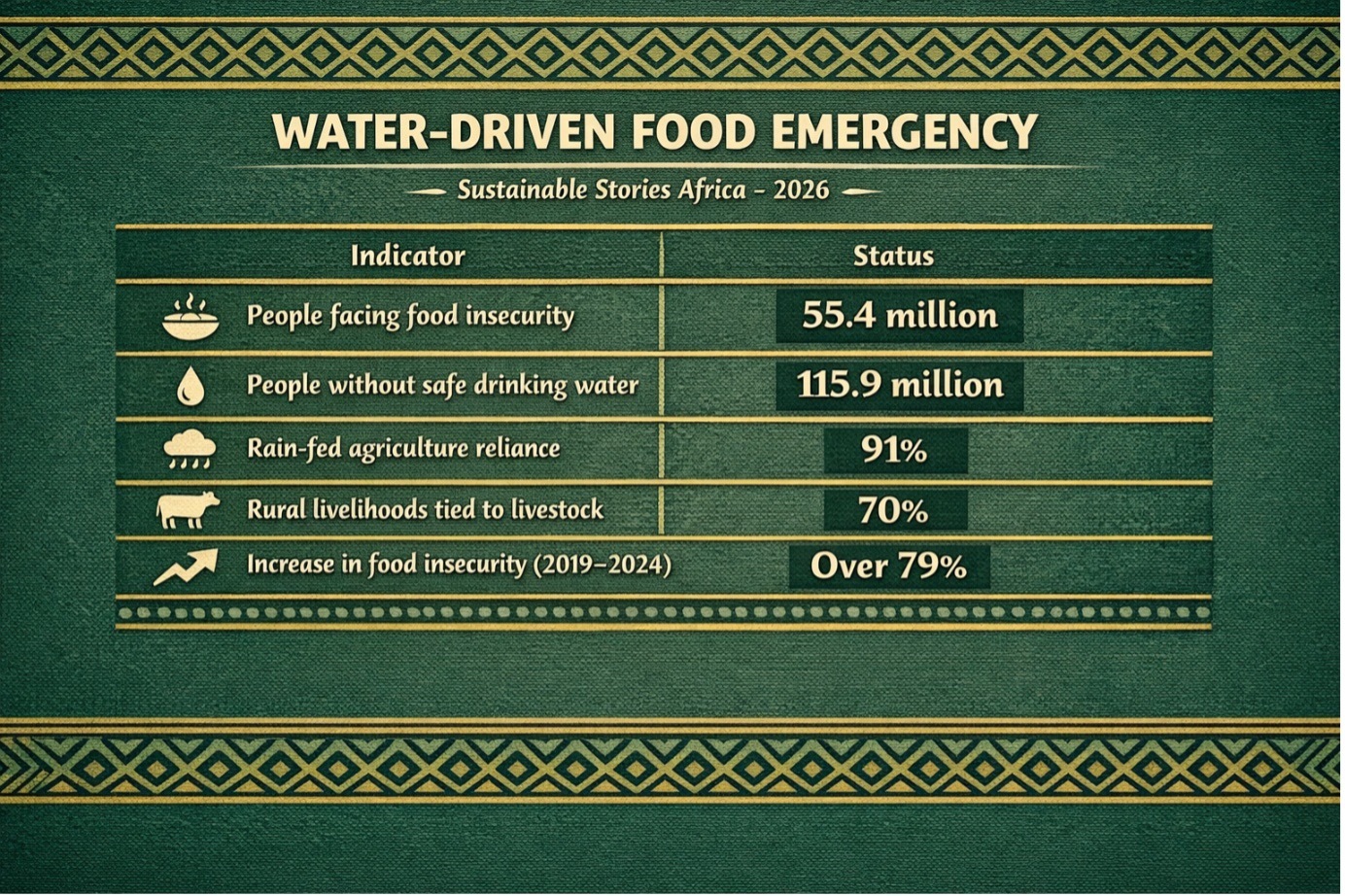

The findings are stark: over 55 million people across these countries face food insecurity, while nearly 116 million lack access to safe drinking water. As climate shocks accelerate, the report argues that food security can no longer be addressed without placing water security at the centre of policy, finance, and humanitarian action.

Africa's Hunger Crisis Has a Water Core

The climate crisis is reshaping Africa's hunger map. Rainfall across parts of eastern and southern Africa has declined by up to 10% since the late twentieth century, destabilising food systems that remain overwhelmingly rain-fed.

Approximately 91% of crops in the affected countries depend on rainfall, while 70% of rural livelihoods rely on livestock.

These vulnerabilities collide with increasingly volatile climate patterns. Consecutive droughts, floods, and flash droughts are eroding resilience faster than communities can recover. Between 2000 and 2022, flash floods became 20 times more frequent, while drought duration increased by 29%.

The result is a hunger crisis that is no longer cyclical, but structurally locked in by water scarcity, climate variability, and weak adaptation systems.

How Climate, Water, and Food Systems Interlock

Rainfall Decline and Agricultural Fragility

Across the eight focus countries, declining rainfall and shifting agro-ecological zones are reducing food production. Climate zones are moving toward hotter and drier conditions, shrinking arable land and destabilising yields. In Kenya alone, more than 136,000 km² shifted from wetter to drier zones between 1980 and 2020.

Maize, which is Africa's staple crop, is particularly exposed. Projections indicate yield declines of 29% in southern Africa and 32% in eastern Africa by mid-century under worsening dryness, directly threatening household food availability.

Food Insecurity Is Rising, Not Stabilising

Food insecurity across the eight countries rose by 79% between 2019 and 2024, reversing years of incremental gains. Ethiopia alone saw the number of food-insecure people increase whooping 175% from 8 million to 22 million in five years. Zambia recorded a 241% increase, while Malawi's food-insecure population nearly tripled.

This surge reflects compounding shocks: climate extremes layered onto pandemic disruptions, economic instability, and fragile public services.

Water Access as a Nutritional Determinant

Access to safe water is now a defining factor in nutrition outcomes. In rural areas, daily water usage often falls far below the 50–100 litres per person recommended for basic health and food preparation. In Mozambique and Zimbabwe, average rural access is estimated to be below 20 litres per day.

Contaminated water worsens malnutrition by undermining food safety, hygiene, and disease resistance. Acute malnutrition rates among children under five are particularly severe in Ethiopia, Somalia, and South Sudan, where unsafe surface water is common.

Health Spillovers: Cholera and Disease

The water-food nexus extends into public health. In 2024, Zambia and Zimbabwe accounted for 50% of Africa's cholera cases, driven by climate-damaged water systems and flooding. These outbreaks further reduce nutrient absorption, weaken immune systems, and strain already fragile health services.

WATER-DRIVEN FOOD EMERGENCY

| Indicator | Status |

|---|---|

| People facing food insecurity | 55.4 million |

| People without safe drinking water | 115.9 million |

| Rain-fed agriculture reliance | 91% |

| Rural livelihoods tied to livestock | 70% |

| Increase in food insecurity (2019–2024) | Over 79% |

What Integrated Water-Food Action Could Change

The report makes clear that water security is not a supporting intervention. It is a precondition for food security. Investments in irrigation, water storage, sanitation, and local water governance could stabilise agricultural output, reduce malnutrition, and protect livelihoods.

Improved hydro-meteorological systems would enable early warning and anticipatory action, reducing disaster mortality rates that are currently six times higher in countries with weak forecasting coverage. Integrated water-food planning would also strengthen women's economic participation by reducing the time spent collecting water, which could be up to 10 km per day in parts of eastern Africa.

The gains are not abstract. Where water access improves, household incomes rise, nutrition improves, and resilience compounds over time.

Why Current Responses Fall Short

Despite the scale of the crisis, sub-Saharan Africa receives just 3 - 4% of global climate finance, even as climate shocks intensify. Humanitarian funding remains short-term, fragmented, and heavily skewed toward emergency relief rather than recovery and resilience.

The report warns that treating water and food insecurity as separate sectors leads to policy failure. Agriculture strategies focused solely on production volumes, export crops, or yield targets overlook the water systems that sustain them. Likewise, WASH interventions disconnected from food systems miss critical nutritional pathways.

PATH FORWARD: Water-Centred Solutions For Food Security

Africa's hunger crisis cannot be solved without fixing its water systems. Integrated water-food strategies. Linking WASH, agriculture, climate adaptation, and nutrition, must replace fragmented responses. Long-term financing, community-led water governance, and climate-resilient infrastructure are now urgent priorities.

Without re-centring water in food security policy, Africa risks locking millions into a permanent cycle of climate-driven hunger.